Chapter 11: Australasia

Executive Summary

Observed changes and impacts

Ongoing climate trends have exacerbated many extreme events (very high confidence). The Australian trends include further warming and sea level rise sea level rise (SLR), with more hot days and heatwaves, less snow, more rainfall in the north, less April–October rainfall in the southwest and southeast and more extreme fire weather days in the south and east. The New Zealand trends include further warming and sea level rise (SLR), more hot days and heatwaves, less snow, more rainfall in the south, less rainfall in the north and more extreme fire weather in the east. There have been fewer tropical cyclones and cold days in the region. Extreme events include Australia’s hottest and driest year in 2019 with a record-breaking number of days over 39°C, New Zealand’s hottest year in 2016, three widespread marine heatwaves during 2016–2020, Category 4 Cyclone Debbie in 2017, seven major hailstorms over eastern Australia and two over New Zealand from 2014–2020, three major floods in eastern Australia and three over New Zealand during 2019–2021 and major fires in southern and eastern Australia during 2019–2020. {11.2.1, Table 11.2, 11.3.8}

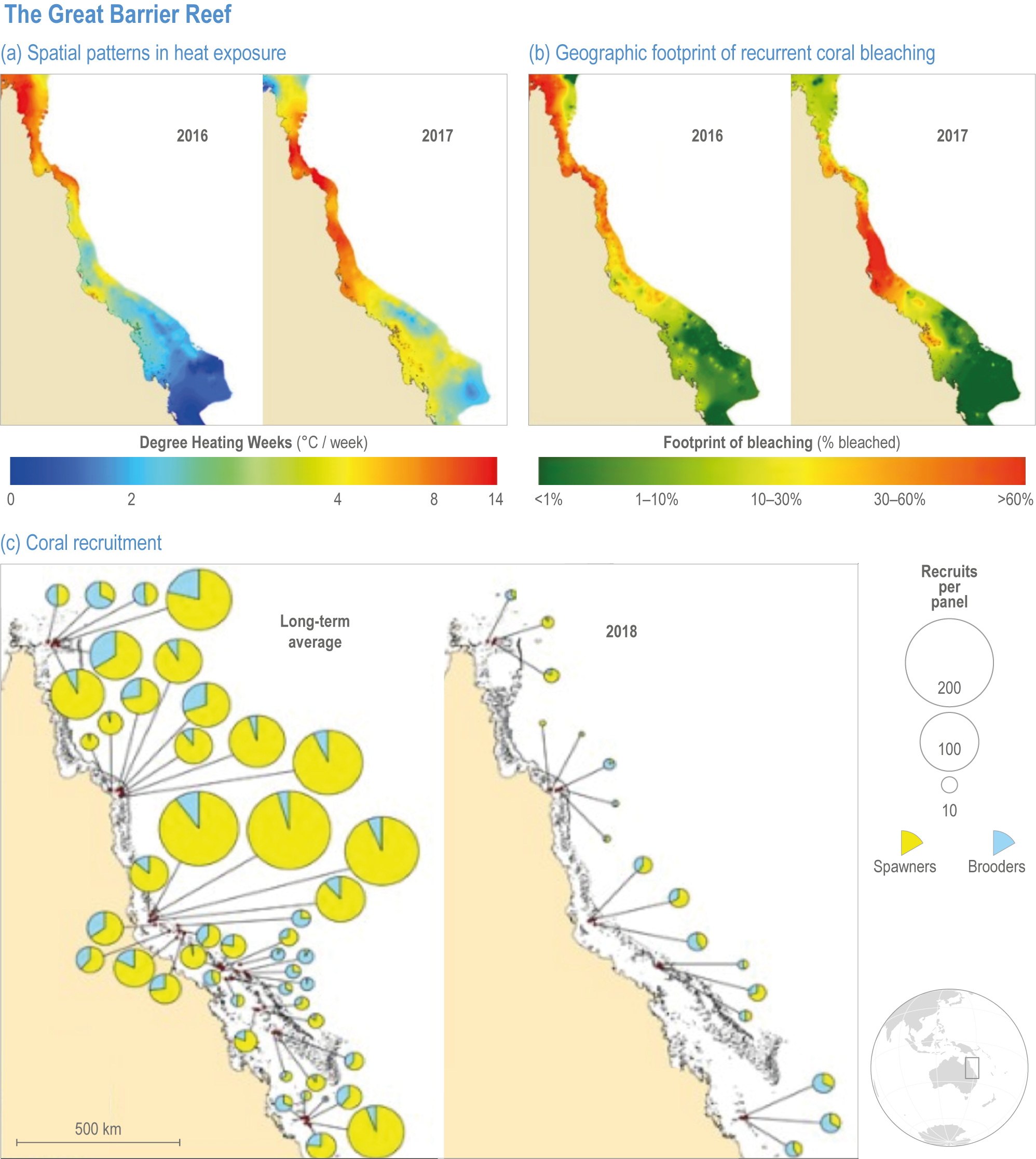

Climate trends and extreme events have combined with exposure and vulnerabilities to cause major impacts for many natural systems, with some experiencing or at risk of irreversible change in Australia (veryhigh confidence) and in New Zealand (high confidence) . For example, warmer conditions with more heatwaves, droughts and catastrophic wildfires have negatively impacted terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. The Bramble Cay melomys, an endemic mammal species, became extinct due to loss of habitat associated with sea level rise (SLR) and storm surges in the Torres Strait. Marine species abundance and distributions have shifted polewards, and extensive coral bleaching events and loss of temperate kelp forests have occurred due to ocean warming and marine heatwaves across the region. In New Zealand’s southern Alps, from 1978 to 2016, the area of 14 glaciers declined 21%, and extreme glacier mass loss was at least 6 times more likely in 2011 and 10 times more likely in 2018 due to climate change. The end-of-summer snowline elevation for 50 glaciers rose 300 m from 1949 to 2019. {11.3.1.1, 11.3.2.1, Table 11.2b, Table 11.4, Table 11.6, Table 11.9}

Climate trends and extreme events have combined with exposure and vulnerabilities to cause major impacts for some human systems (high confidence). Socioeconomic costs arising from climate variability and change have increased. Extreme heat has led to excess deaths and increased rates of many illnesses. Nuisance and extreme coastal flooding have increased due to sea level rise (SLR) superimposed upon high tides and storm surges in low-lying coastal and estuarine locations, including impacts on cultural sites, traditions and lifestyles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in Australia and Tangata Whenua Māori in New Zealand. Droughts have caused financial and emotional stress in farm households and rural communities. Tourism has been negatively affected by coral bleaching, fires, poor ski seasons and receding glaciers. Governments, business and communities have experienced major costs associated with extreme weather, droughts and sea level rise (SLR). {11.3, 11.4, 11.5.2, Table 11.2, Boxes 11.1–11.6}

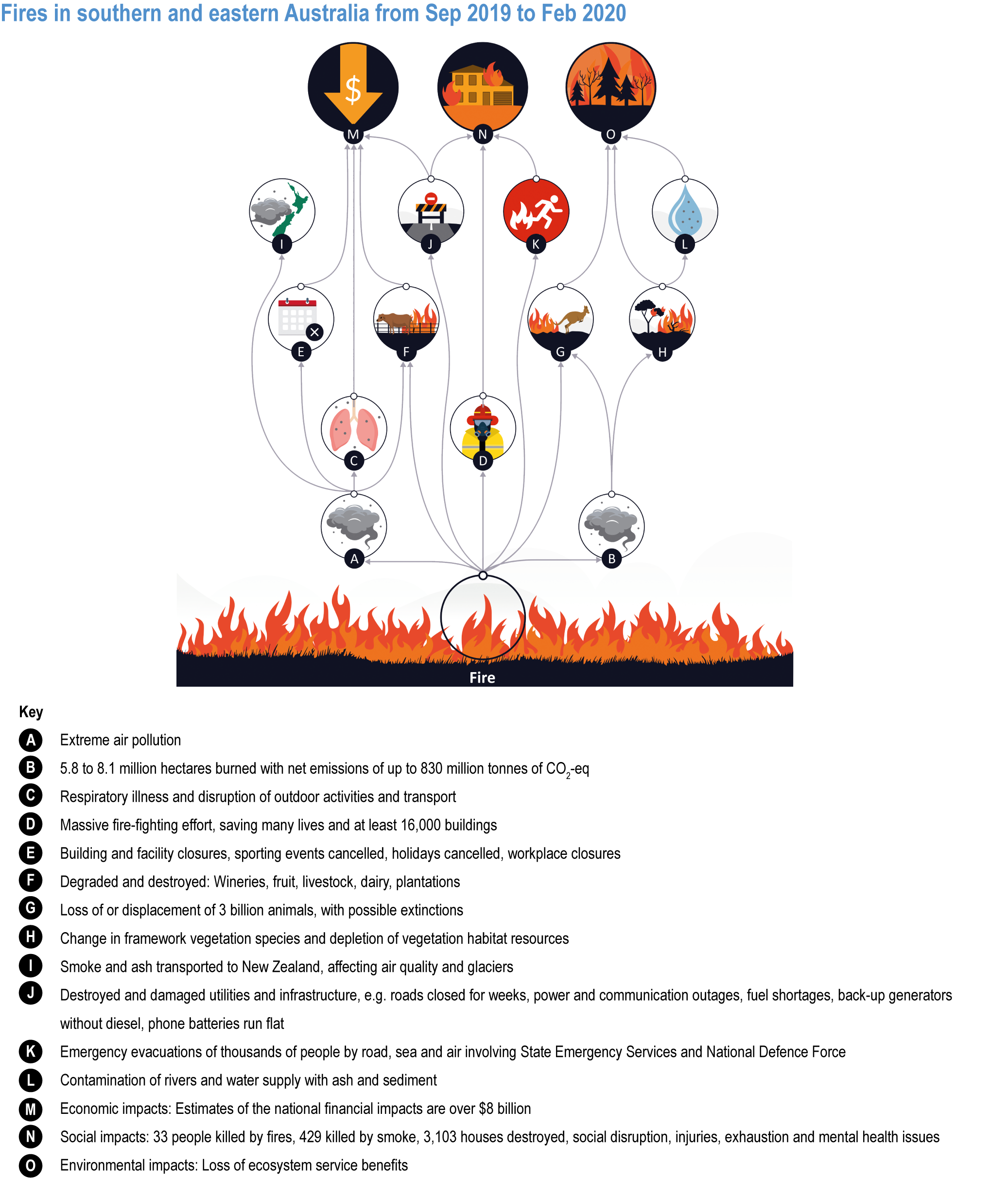

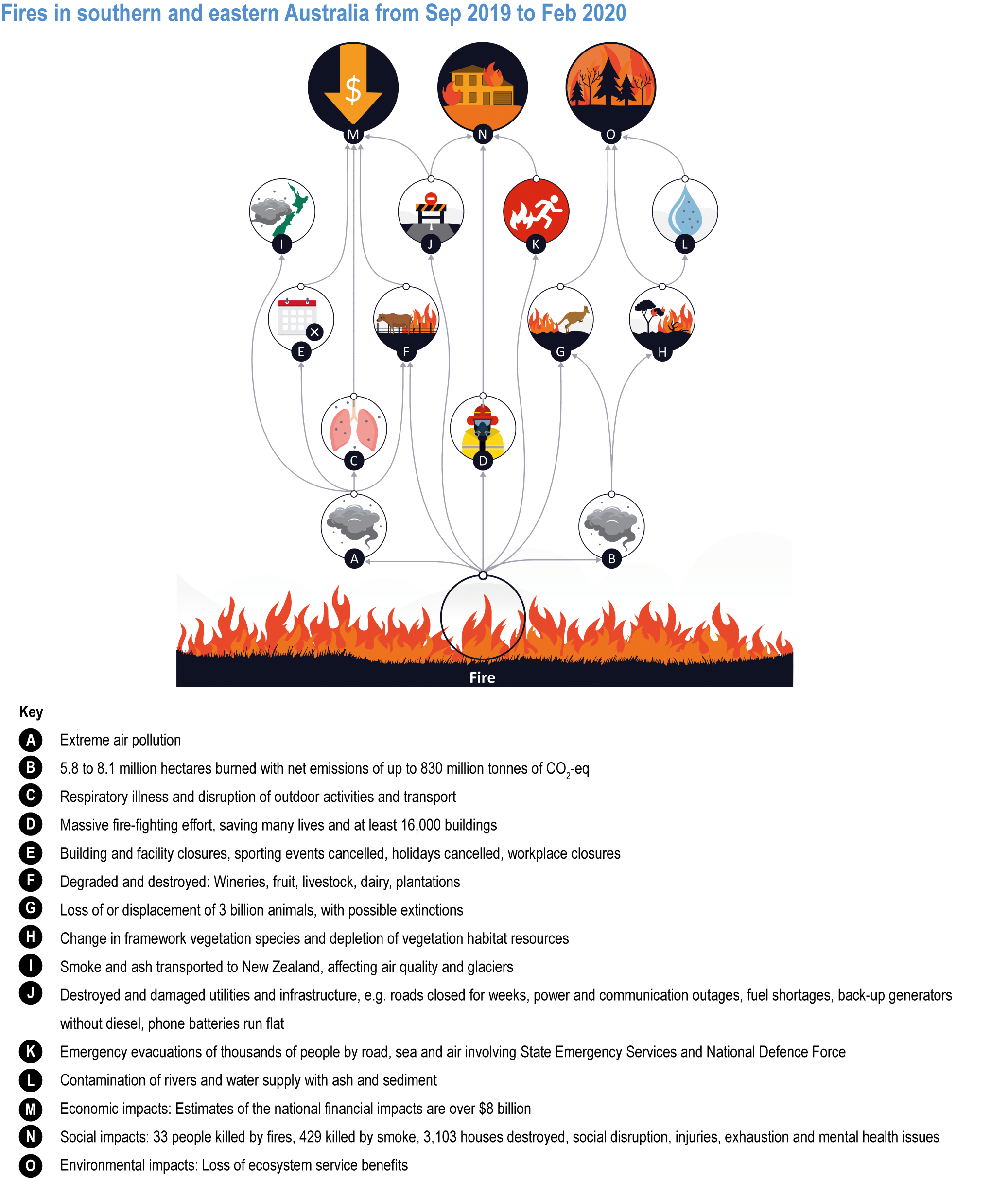

Climate impacts are cascading and compounding across sectors and socioeconomic and natural systems (high confidence). Complex connections are generating new types of risks, exacerbating existing stressors and constraining adaptation options. An example is the impacts that cascade between interdependent systems and infrastructure in cities and settlements. Another example is the 2019–2020 southeast Australia wildfires, which burned 5.8 to 8.1 million hectares, with 114 listed threatened species losing at least half of their habitat and 49 losing over 80%, over 3,000 houses destroyed, 33 people killed, a further 429 deaths and 3230 hospitalisations due to cardiovascular or respiratory conditions, AUD$1.95 billion in health costs, AUD$2.3 billion in insured losses and AUD$3.6 billion in losses for tourism, hospitality, agriculture and forestry. {11.5.1, Box 11.1}

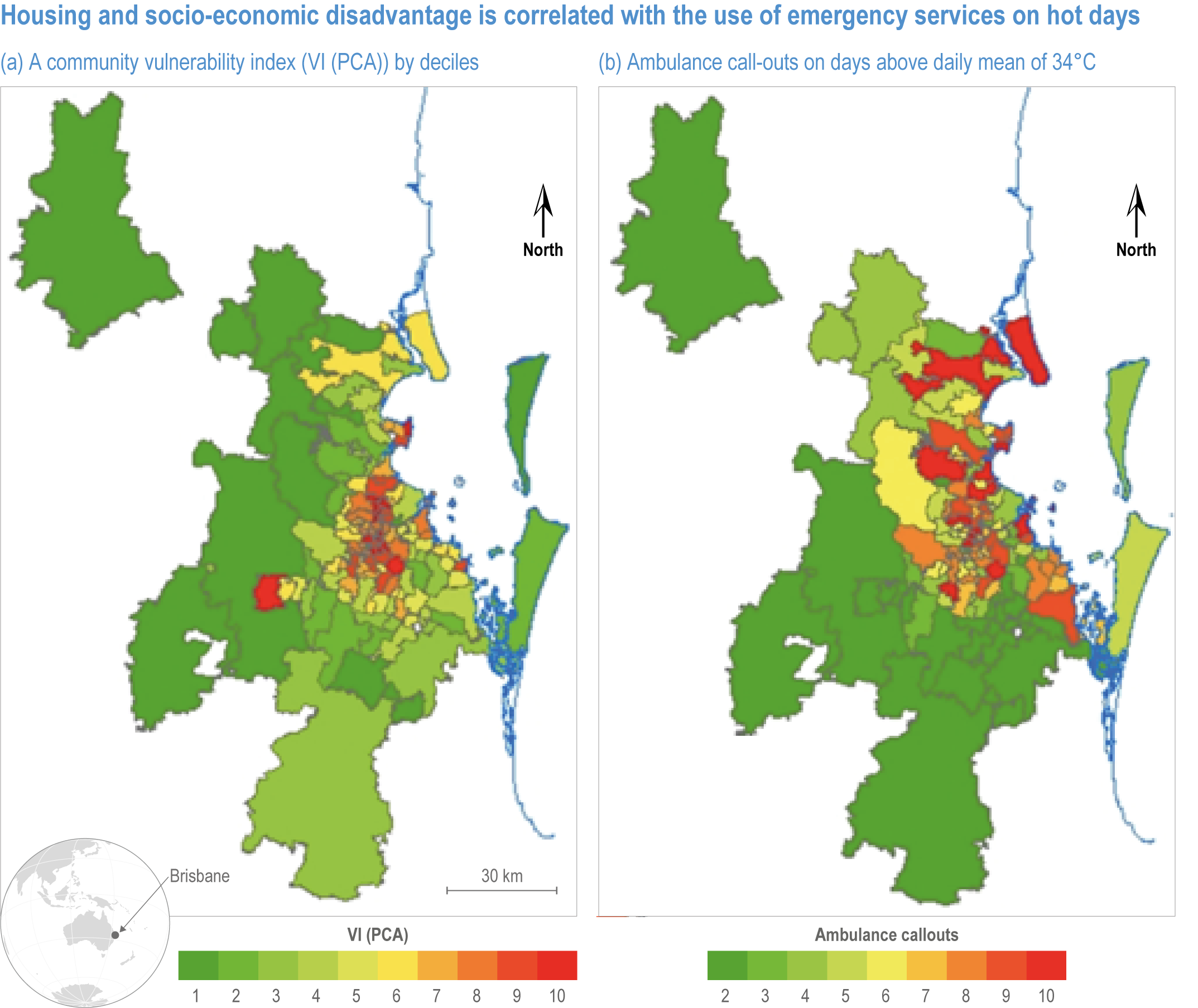

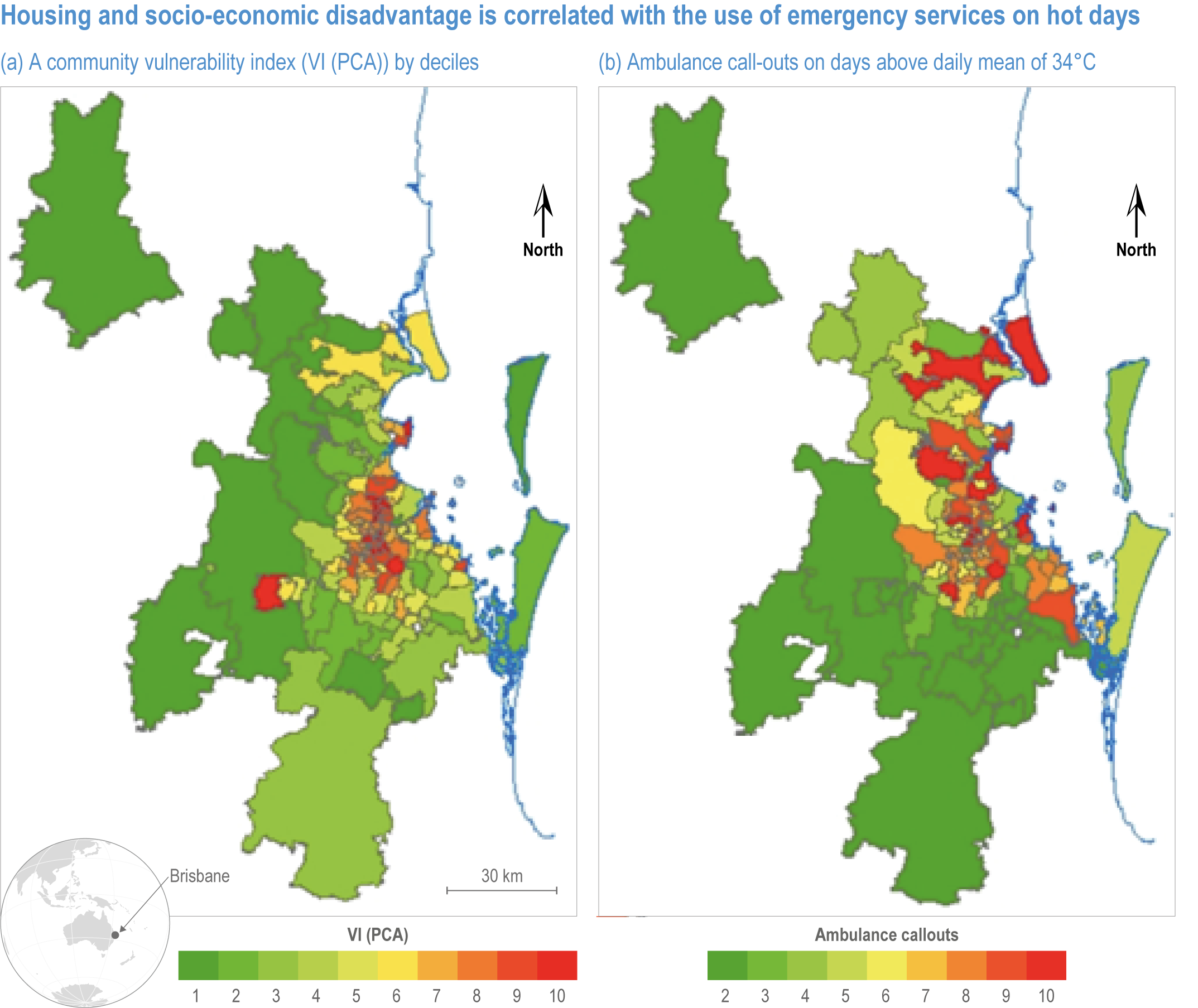

Increasing climate risks are projected to exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and social inequalities and inequities (high confidence). These include inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples and between generations, rural and urban areas, incomes and health status, increasing the climate risks and adaptation challenges faced by some groups and places. Resultant climate change impacts include the displacement of some people and businesses and threaten social cohesion and community well-being. {11.3.5, 11.3.6, 11.3.10, 11.4}

Projected impacts and key risks

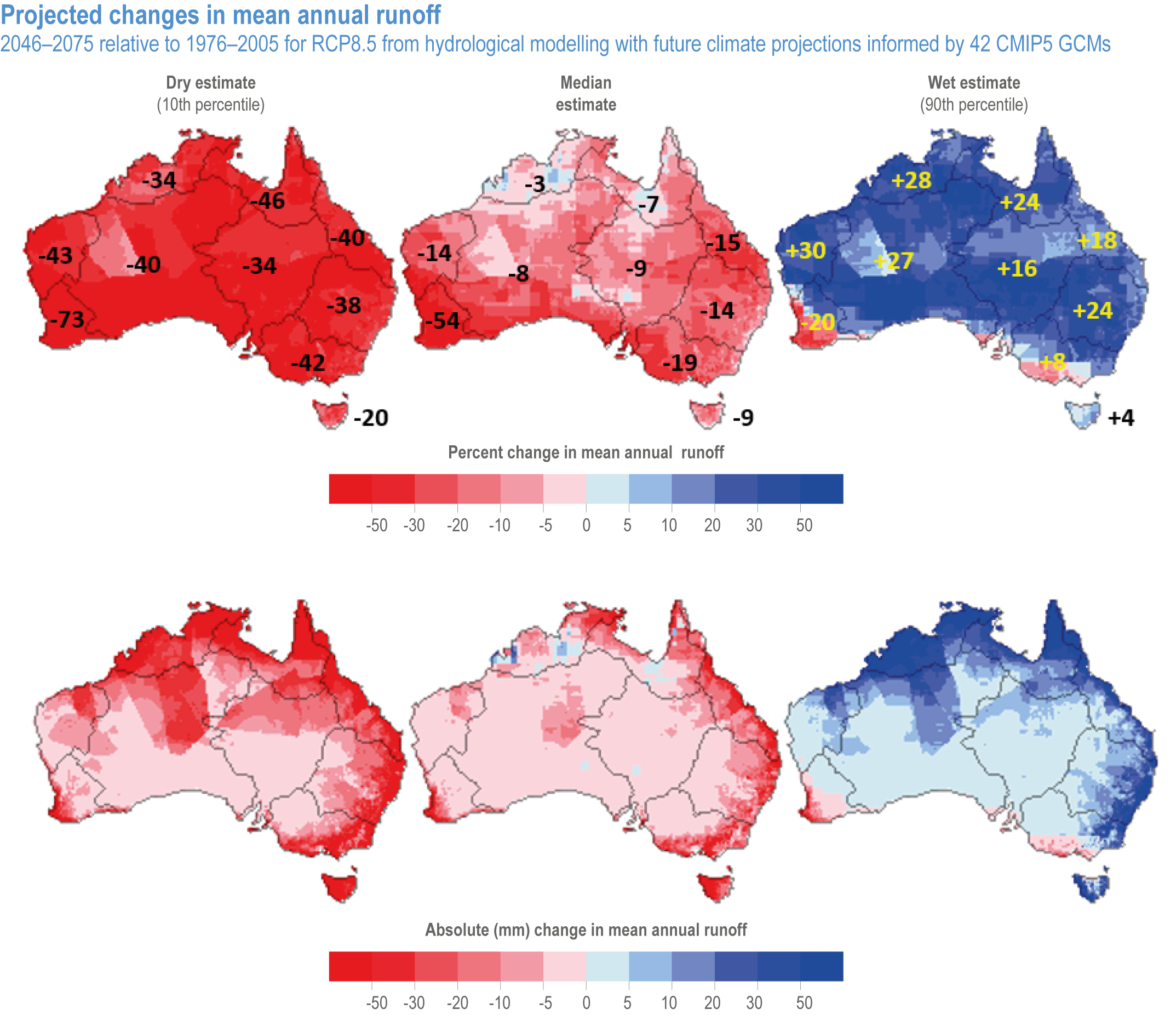

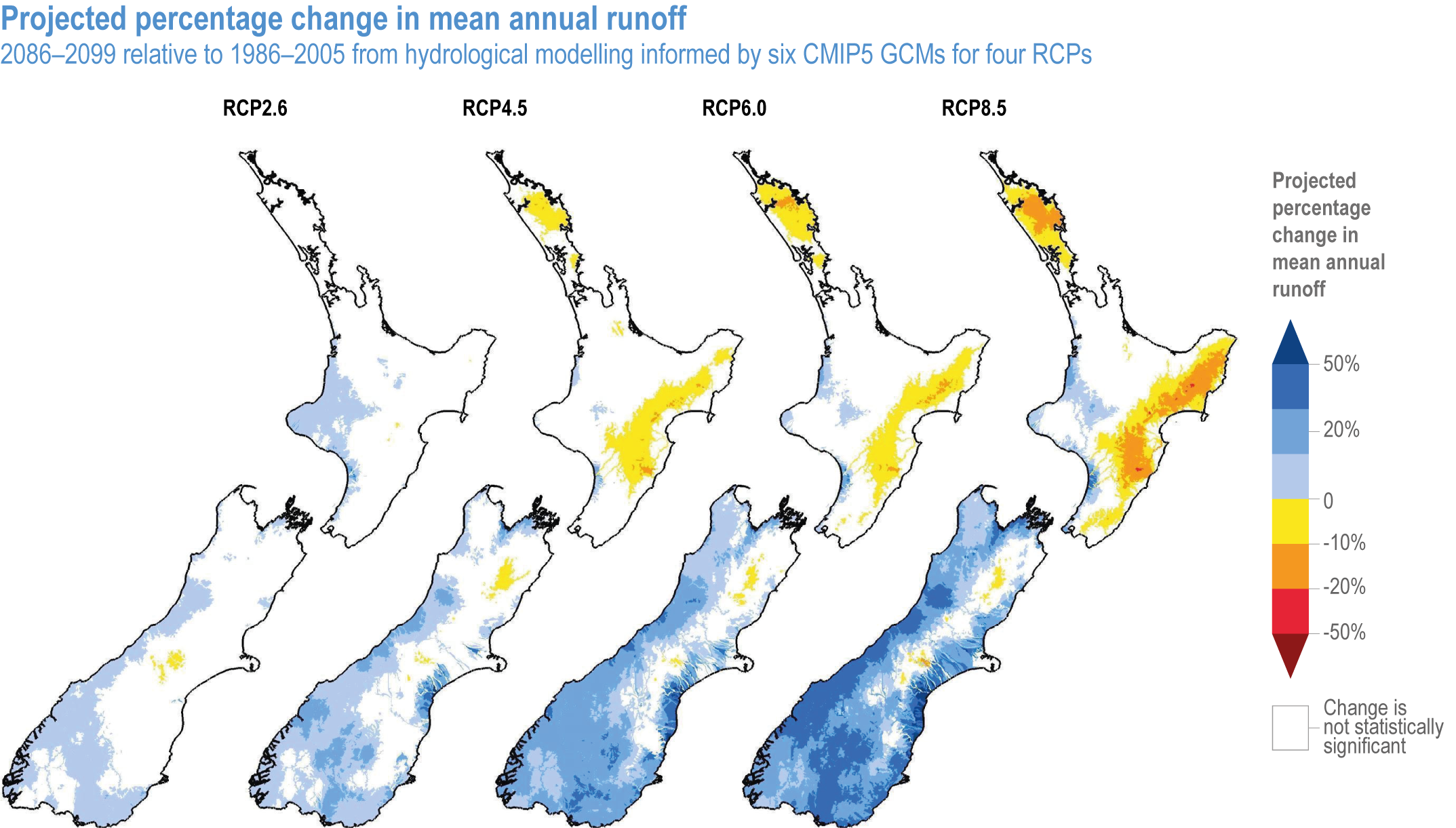

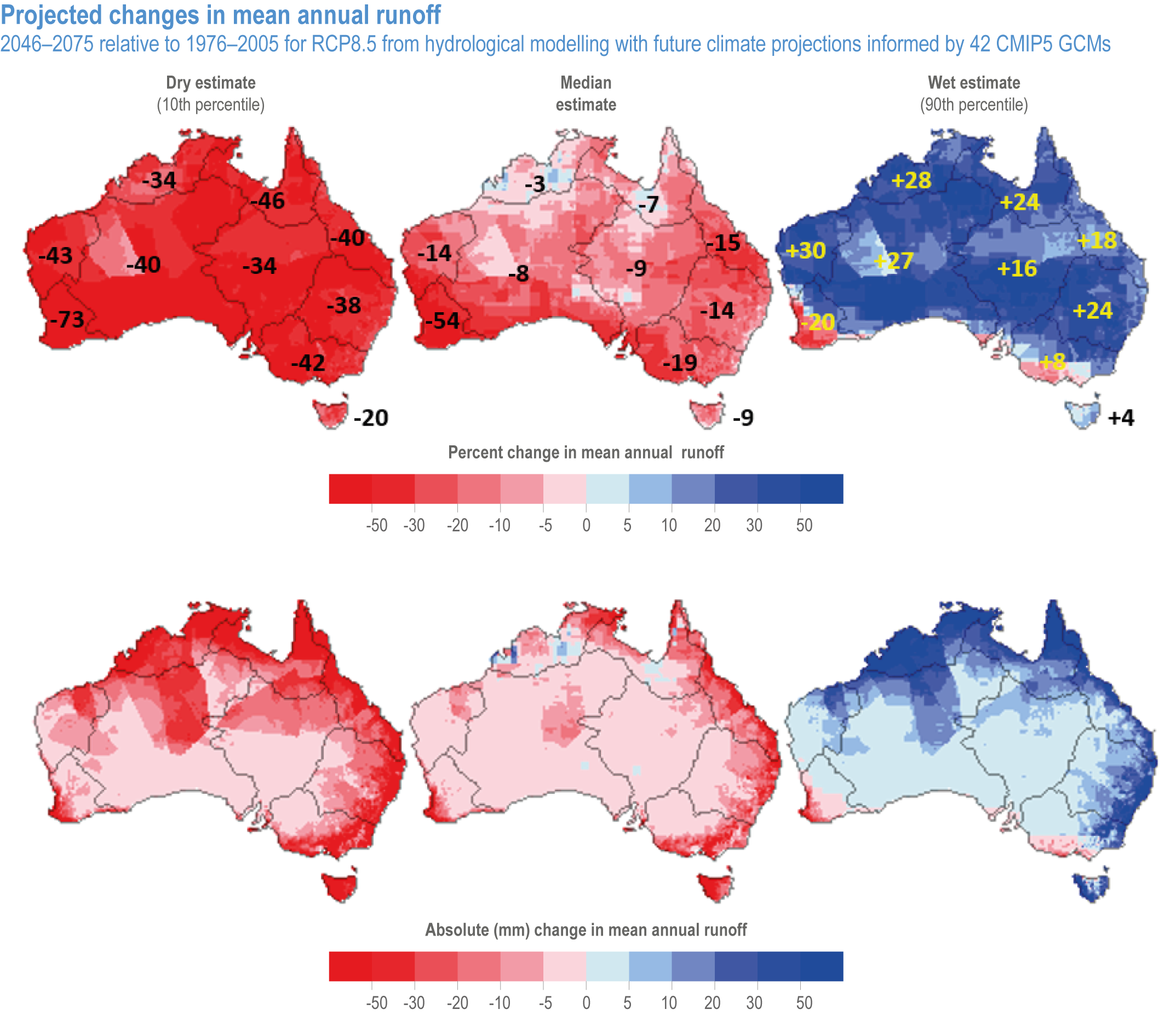

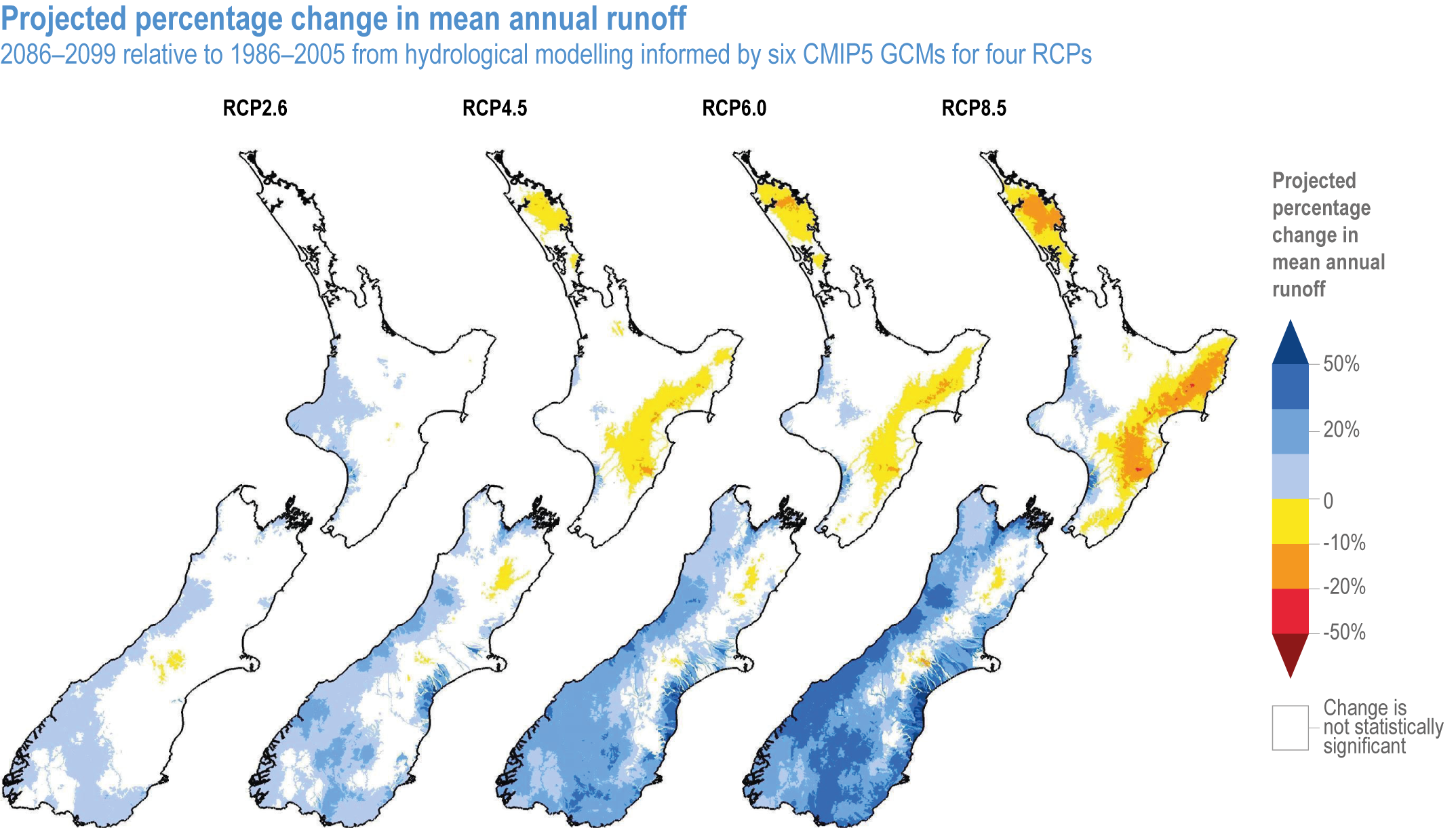

Further climate change is inevitable, with the rate and magnitude largely dependent on the emission pathway (very high confidence1 ). Ongoing warming is projected, with more hot days and fewer cold days (very high confidence). Further sea level rise (SLR), ocean warming and ocean acidification are projected (very high confidence). Less winter and spring rainfall is projected in southern Australia, with more winter rainfall in Tasmania, less autumn rainfall in southwestern Victoria and less summer rainfall in western Tasmania (medium confidence), with uncertain rainfall changes in northern Australia. In New Zealand, more winter and spring rainfall is projected in the west and less in the east and north, with more summer rainfall in the east and less in the west and central North Island (medium confidence). In New Zealand, ongoing glacier retreat is projected (very high confidenc e). More extreme fire weather is projected in southern and eastern Australia (high confidence) and over northern and eastern New Zealand (medium confidence). Increased drought frequency is projected for southern and eastern Australia and northern New Zealand (medium confidence). Increased heavy rainfall intensity is projected, with fewer tropical cyclones and a greater proportion of severe cyclones (medium confidence). {11.2.2, Table 11.3, Box 11.6}

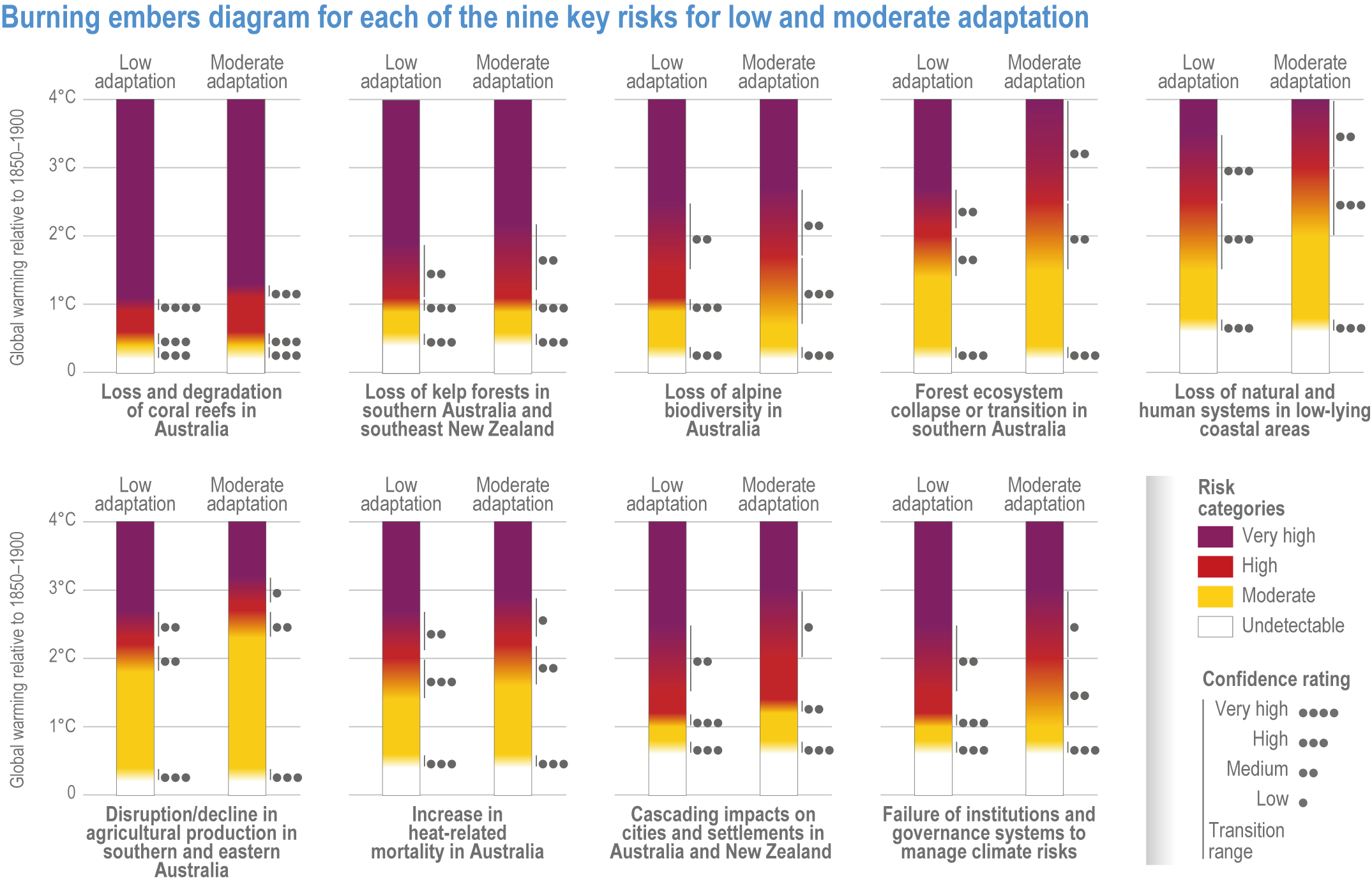

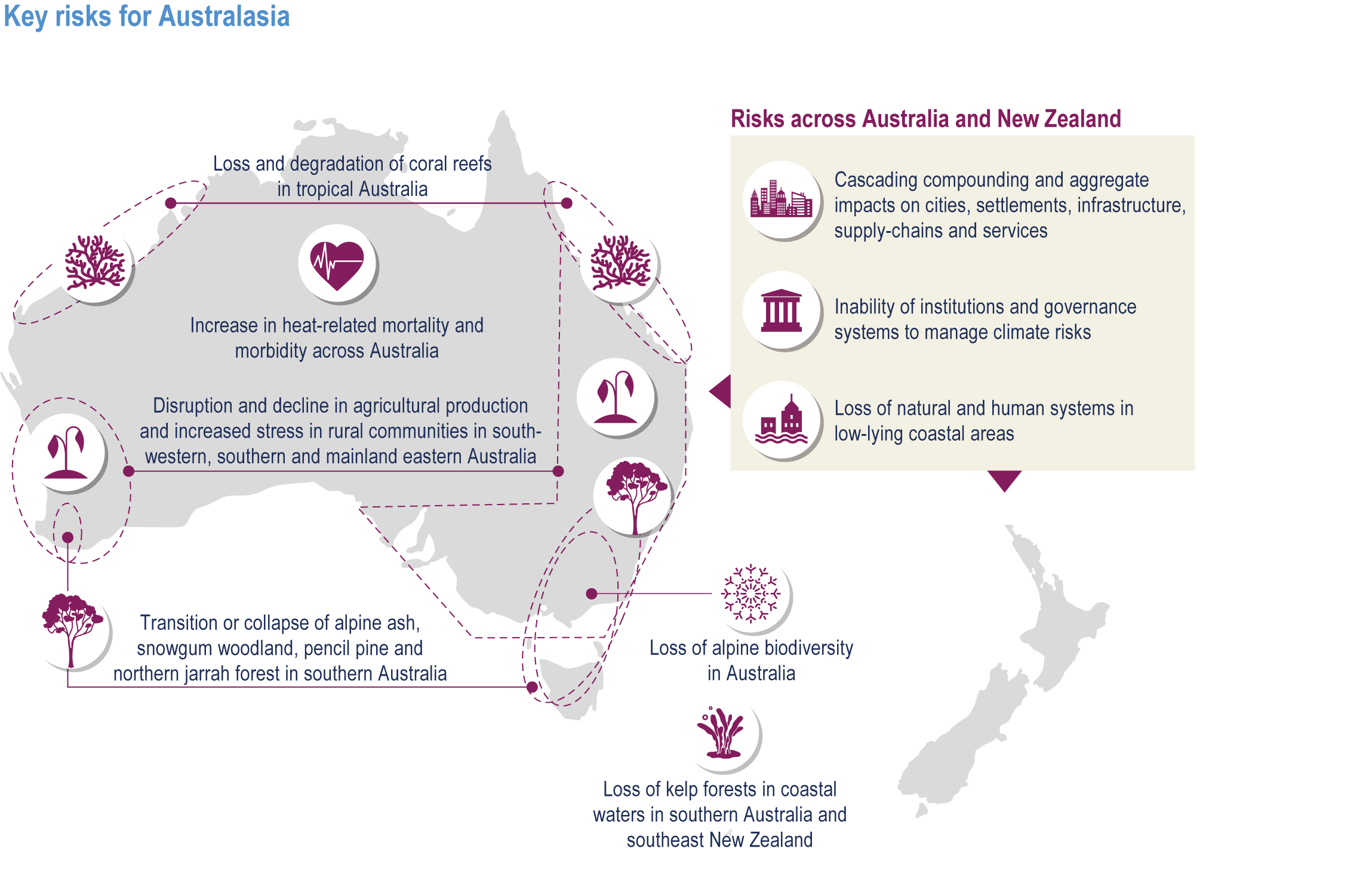

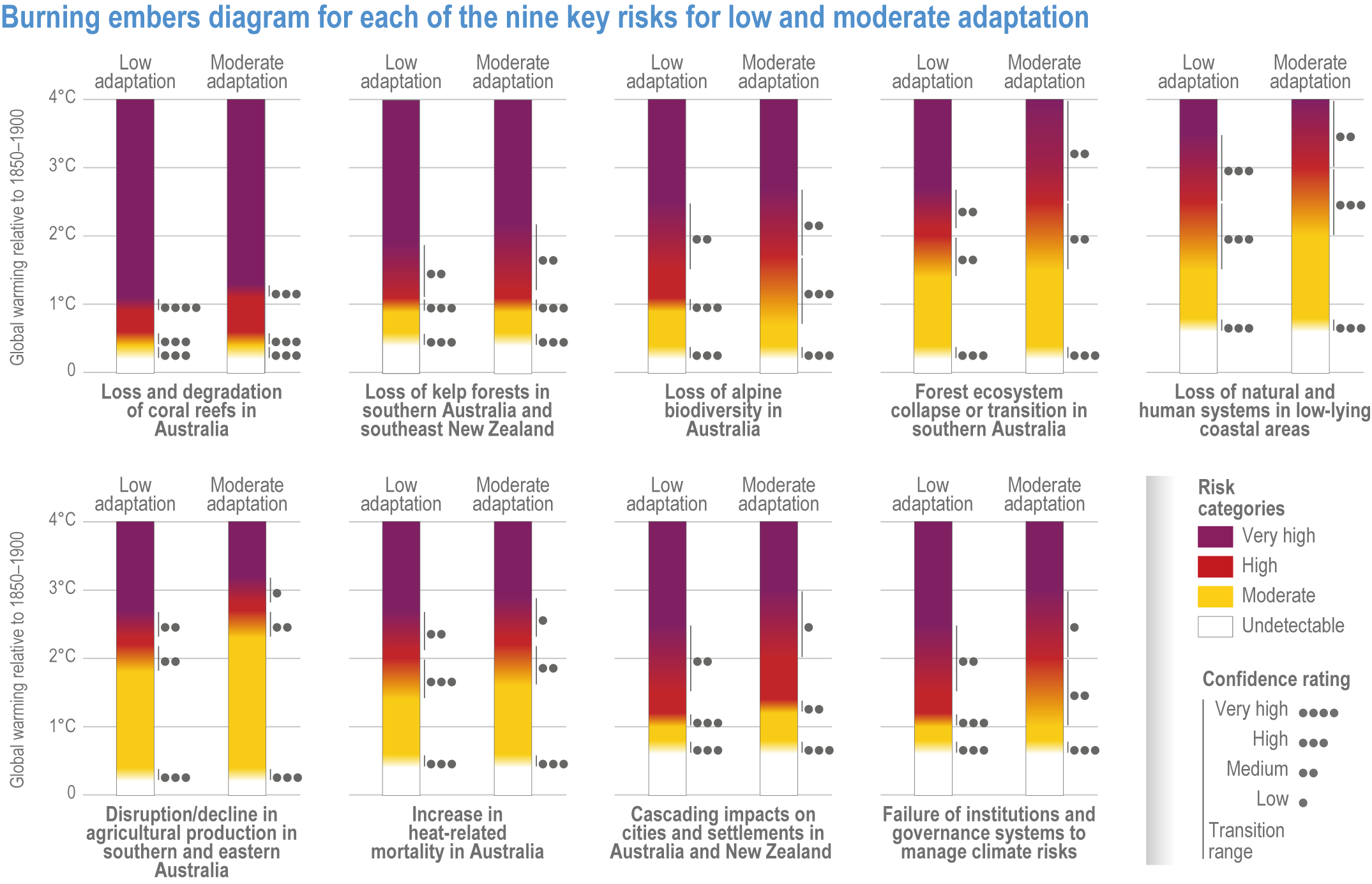

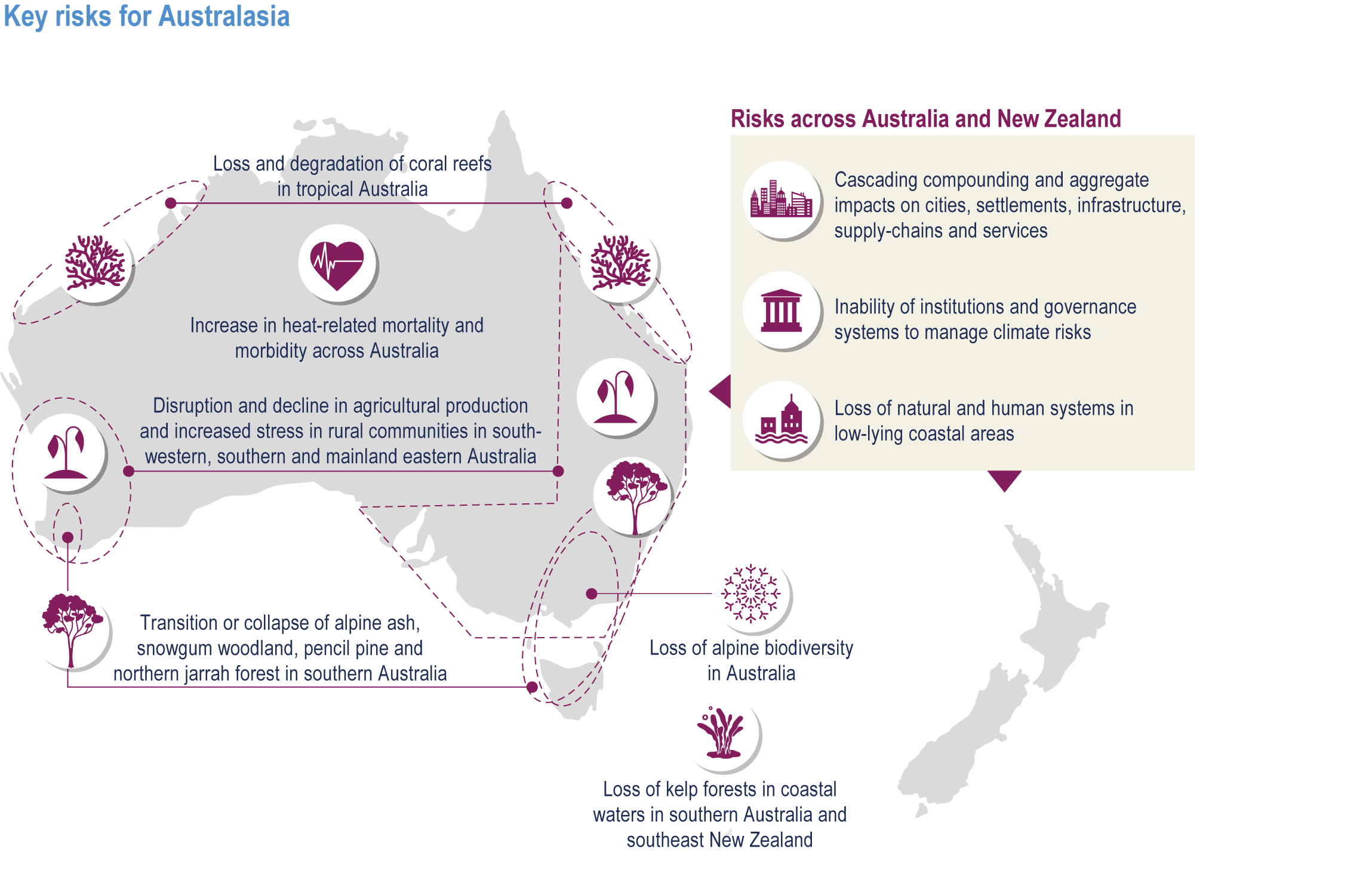

Climate risks are projected to increase for a wide range of systems, sectors and communities, which are exacerbated by underlying vulnerabilities and exposures (high confidence) {11.3; 11.4}. Nine key risks have been identified, based on magnitude, likelihood, timing and adaptive capacity {11.6, Table 11.14}:

Ecosystems at critical thresholds, where recent climate change has caused significant damage and further climate change may cause irreversible damage, with limited scope for adaptation

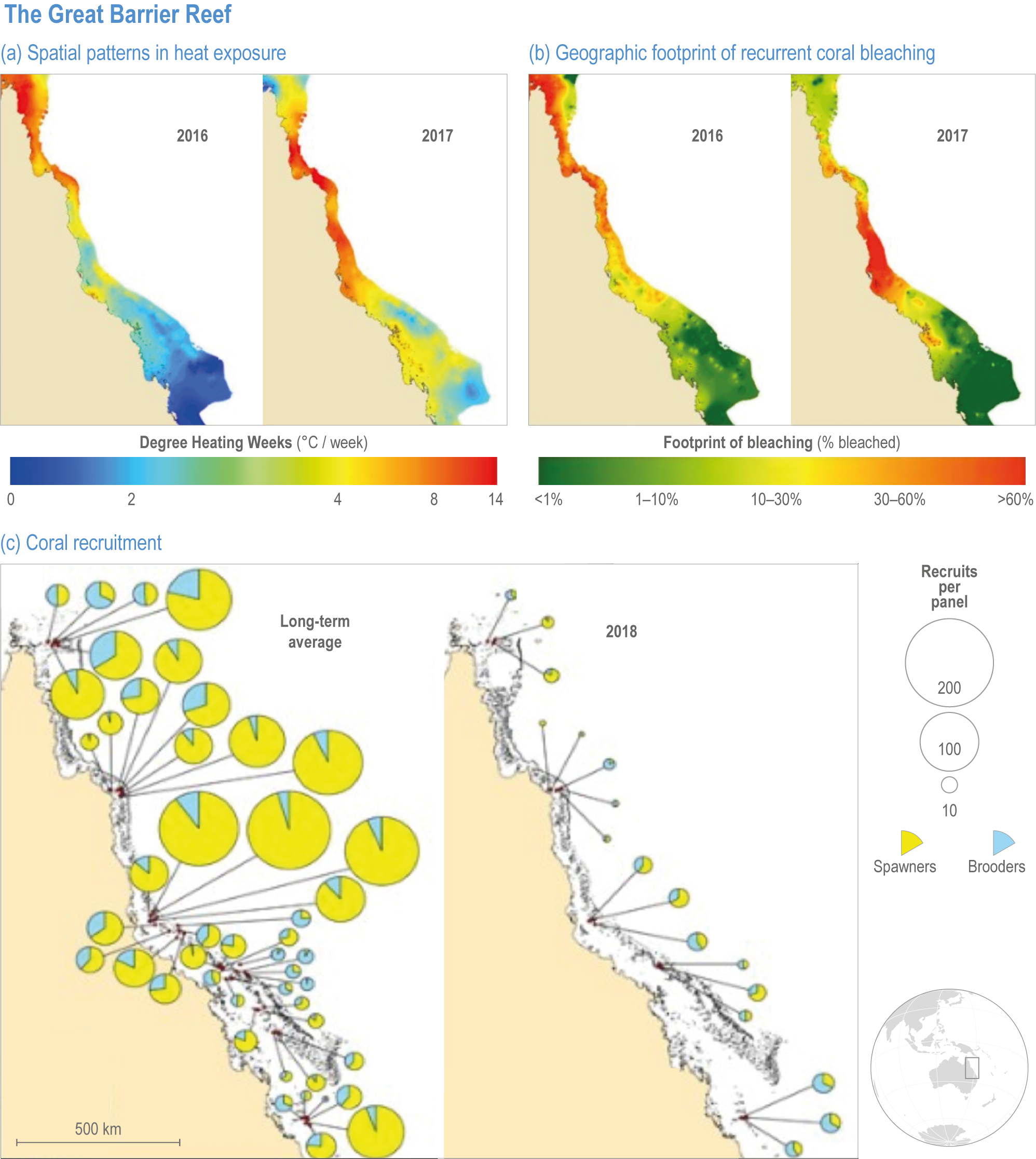

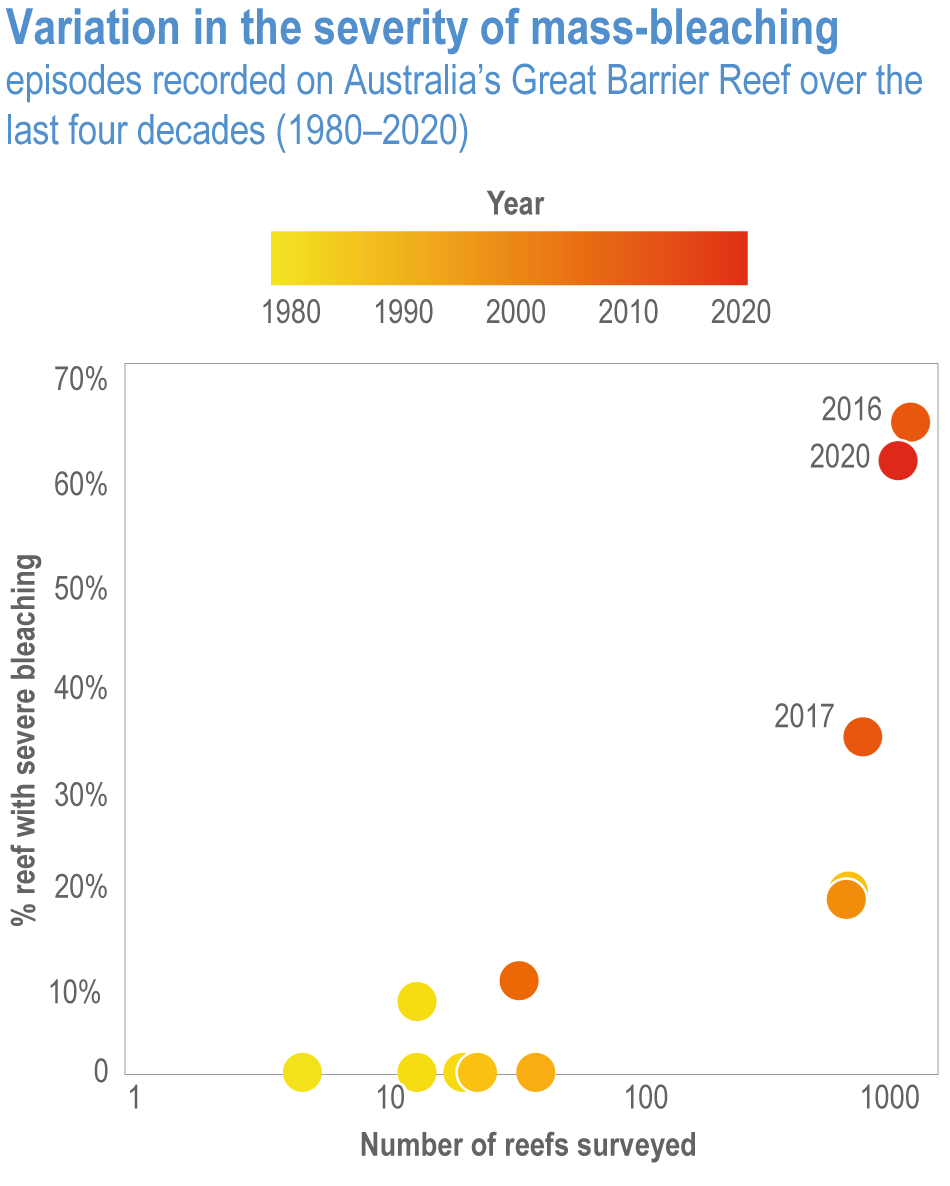

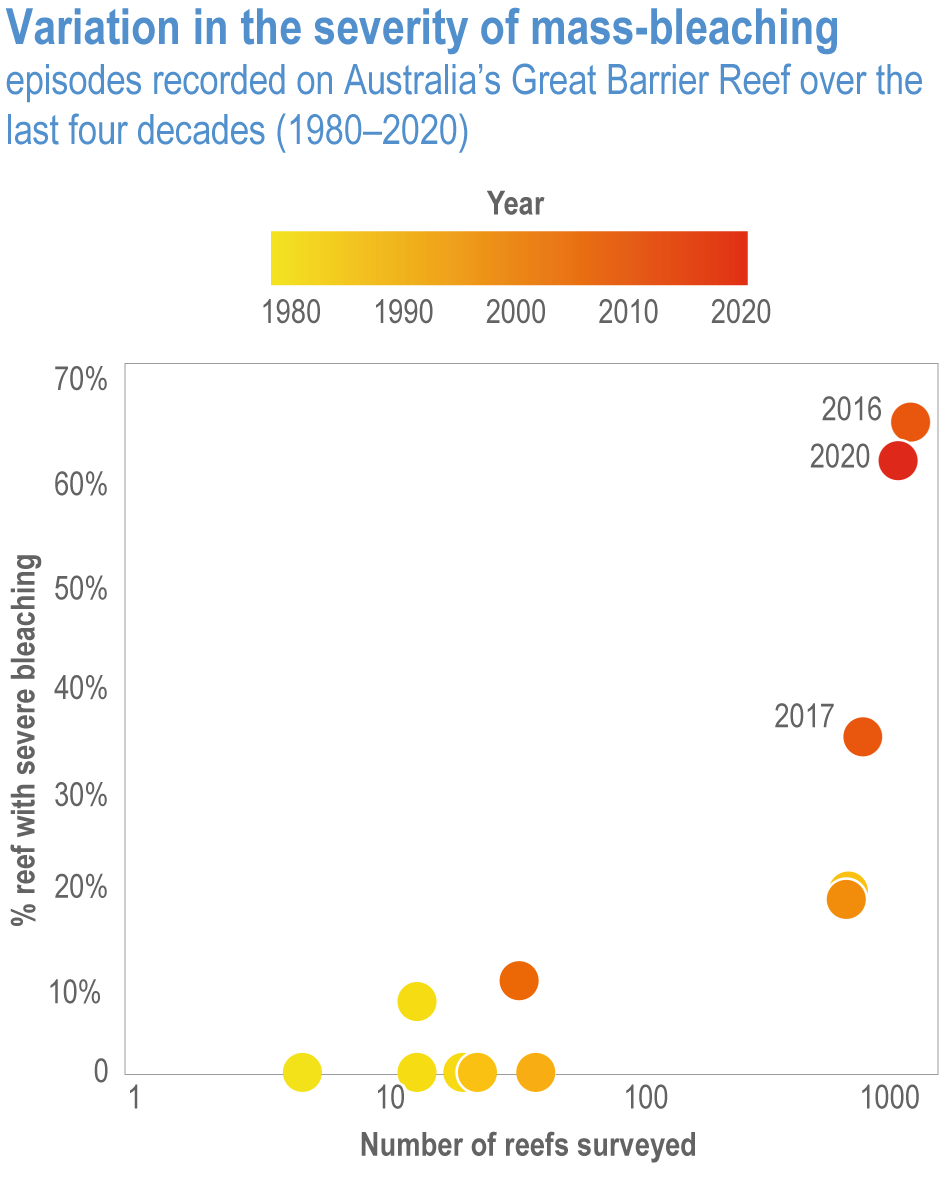

- Loss and degradation of coral reefs and associated biodiversity and ecosystem service values in Australia due to ocean warming and marine heatwaves. For example three marine heatwaves on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) during 2016–2020 caused significant bleaching and loss (very high confidence). {11.3.2.1, 11.3.2.2, Box 11.2}

- Loss of alpine biodiversity in Australia due to less snow. For example loss of alpine vegetation communities (snow patch Feldmark and short alpine herb-fields) and increased stress on snow-dependent plant and animal species (high confidence). {11.3.1.1, 11.3.1.2}

Key risks that have potential to be severe but can be reduced substantially by rapid, large-scale and effective mitigation and adaptation

- Transition or collapse of alpine ash, snowgum woodland, pencil pine and northern jarrah forests in southern Australia due to hotter and drier conditions with more fires. For example declining rainfall in southern Australia over the past 30 years, has led to drought-induced canopy dieback across a range of forest and woodland types and death of fire-sensitive tree species due to unprecedented wildfires (high confidence). {11.3.1.1, 11.3.1.2}

- Loss of kelp forests in southern Australia and southeast New Zealand due to ocean warming, marine heatwaves and overgrazing by climate-driven range extensions of herbivore fish and urchins. For example less than 10% of giant kelp in Tasmania was remaining by 2011 due to ocean warming (high confidence). {11.3.2.1, 11.3.2.2}

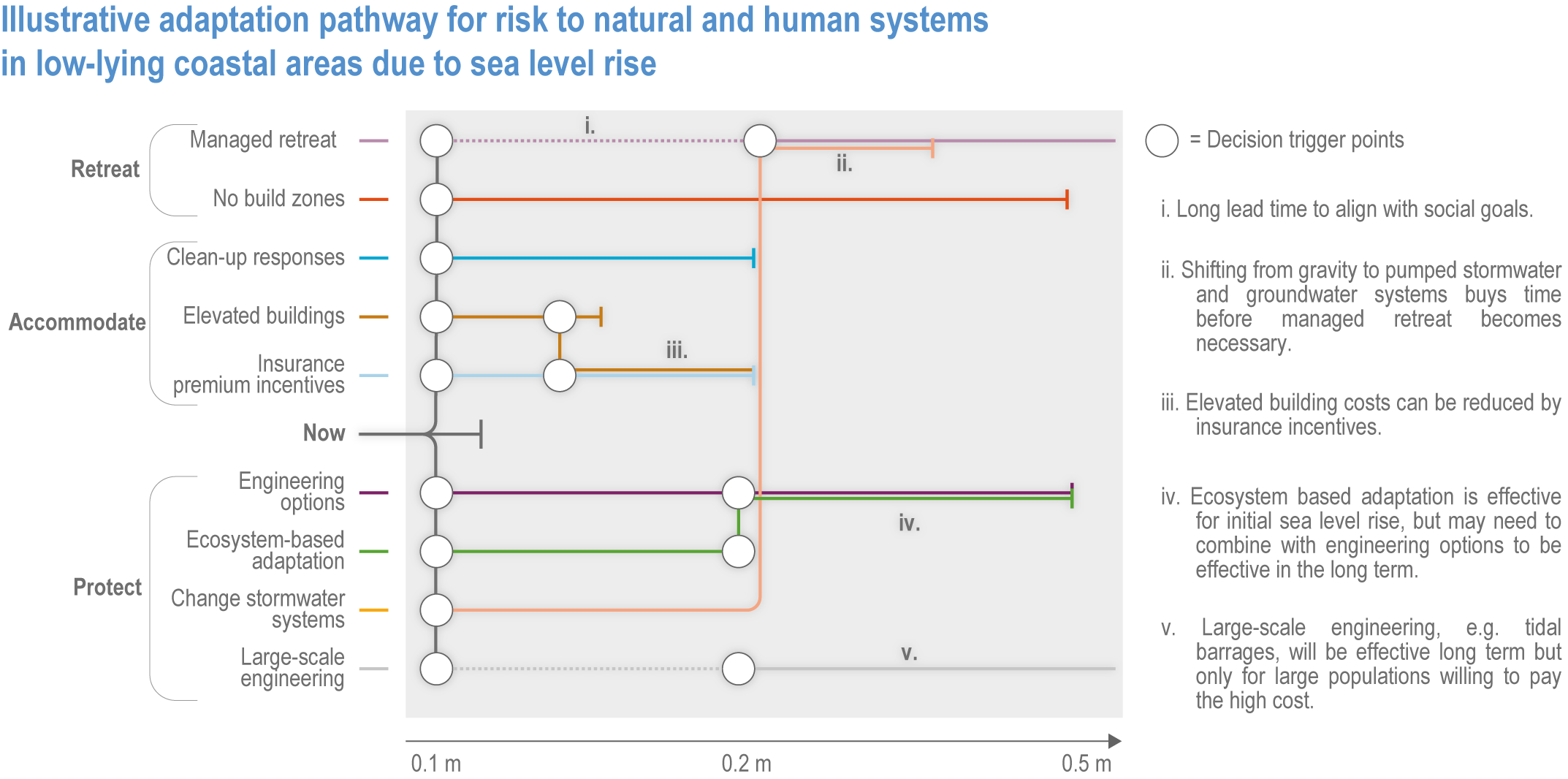

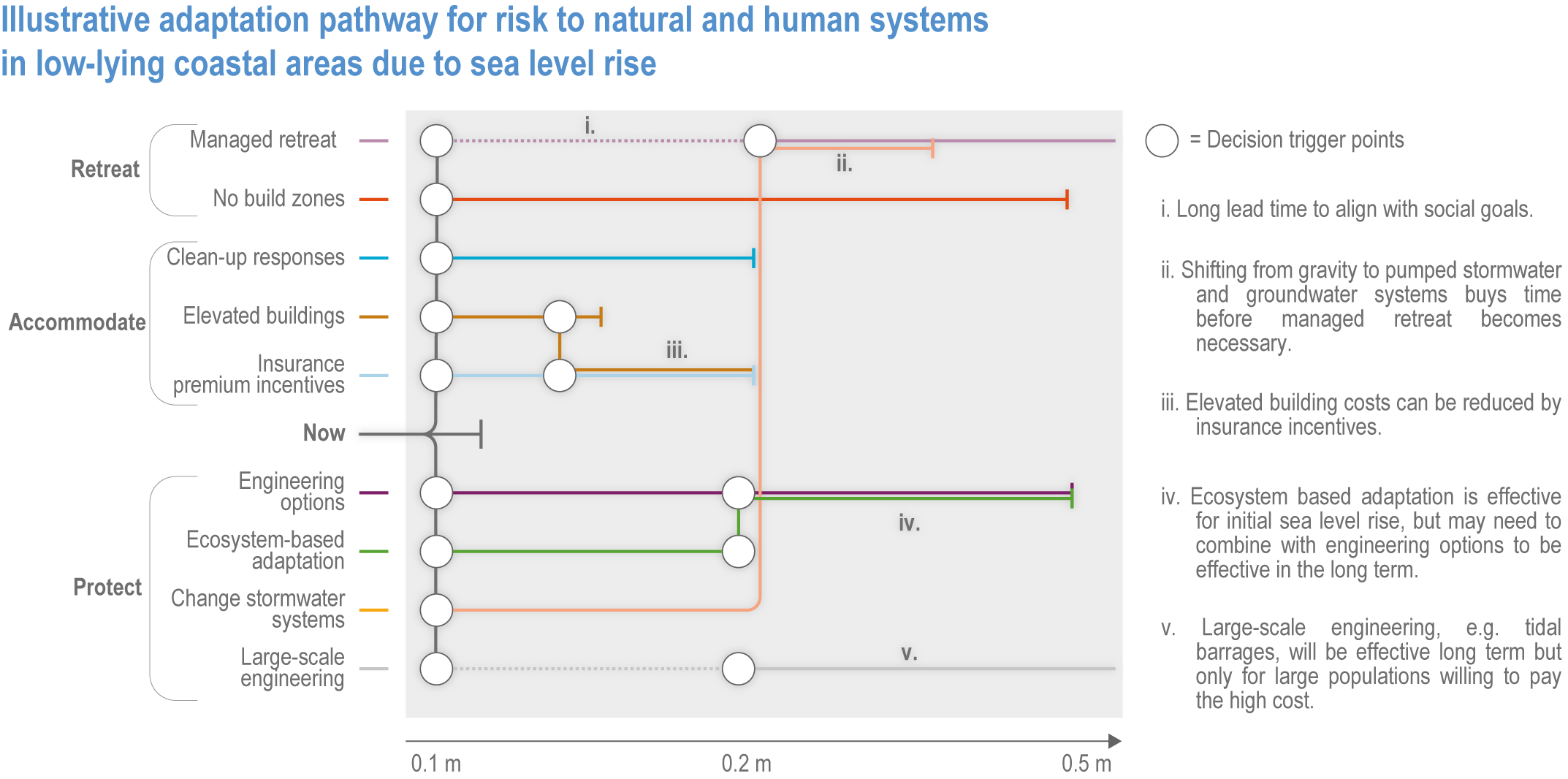

- Loss of natural and human systems in low-lying coastal areas due to sea level rise (SLR). For example for 0.5 m sea level rise (SLR), the value of buildings in New Zealand exposed to 1-in-100-year coastal inundation could increase by NZ$12.75 billion and the current 1-in-100-year flood in Australia could occur several times a year (high confidence). {11.3.5; Box 11.6}

- Disruption and decline in agricultural production and increased stress in rural communities in southwestern, southern and eastern mainland Australia due to hotter and drier conditions. For example by 2050, a decline in median wheat yields of up to 30% in southwestern Australia and up to 15% in South Australia and increased heat stress in livestock by 31–42 days per year (high confidence). {11.3.4; 11.3.5; Box 11.3}

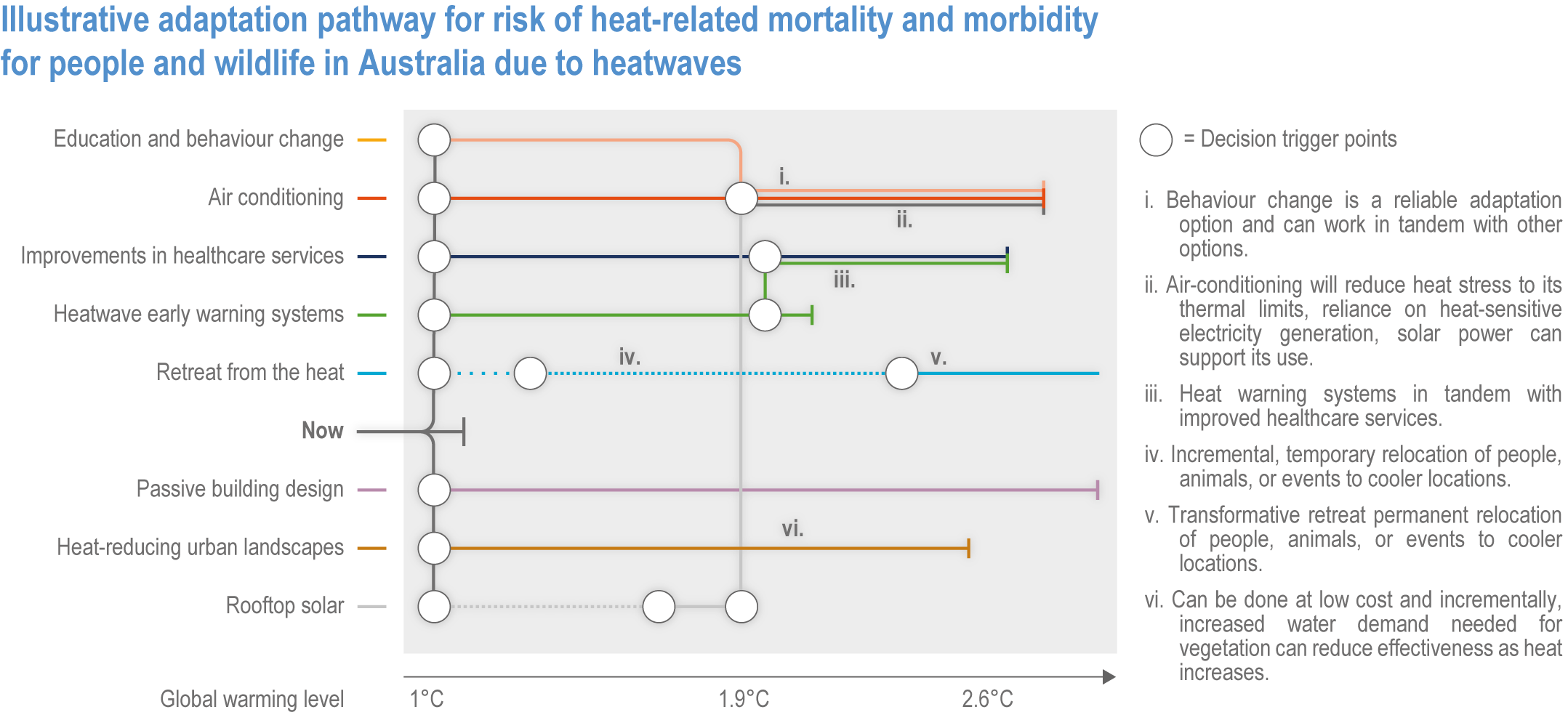

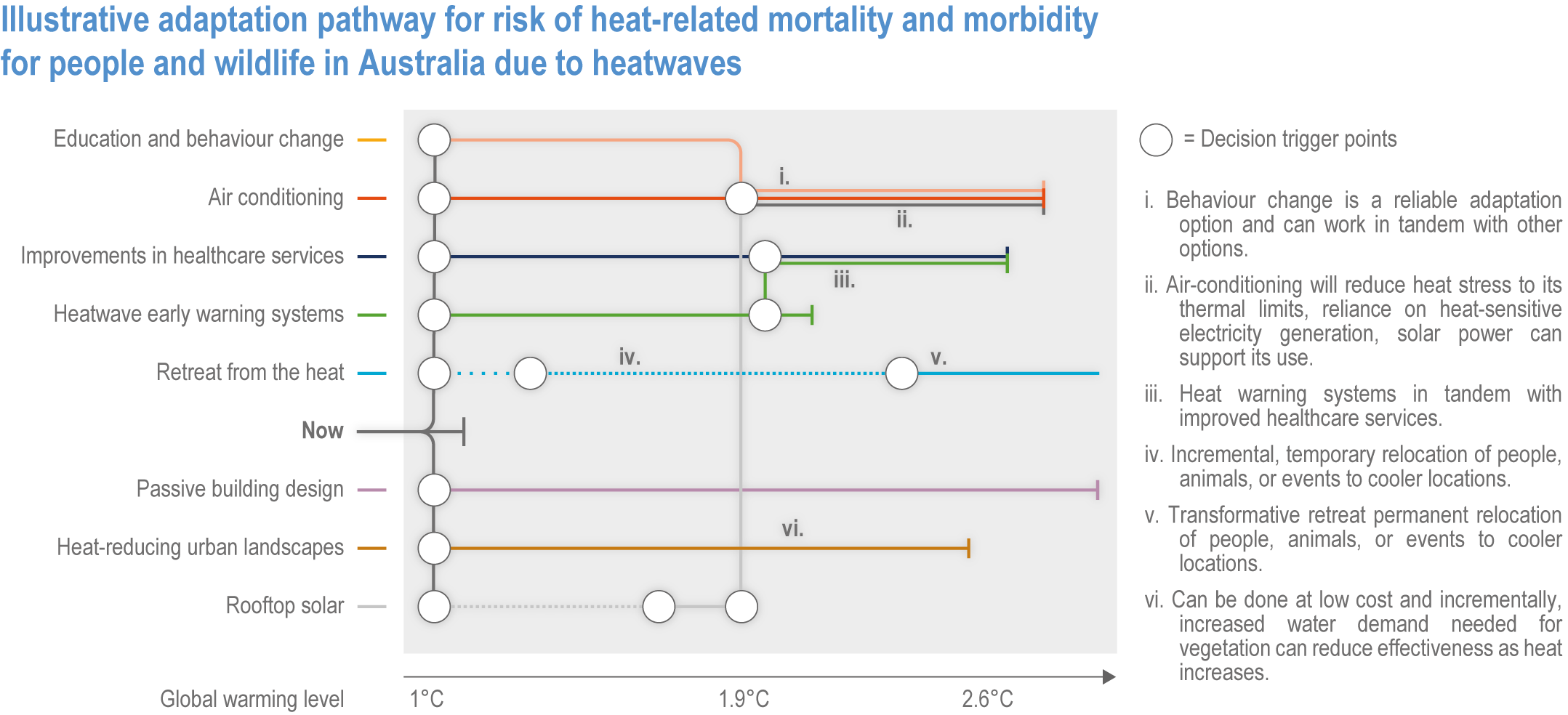

- Increase in heat-related mortality and morbidity for people and wildlife in Australia due to heatwaves. For example heat-related excess deaths in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane are projected to increase by about 300/year (low emission pathway) to 600/year (high emission pathway) during the 2031–2080 period relative to 142/year in the period 1971–2020 (high confidence). {11.3.1, 11.3.5.1, 11.3.5.2, 11.3.6.1, 11.3.6.2}

Key cross-sectoral and system-wide risk

- Cascading, compounding and aggregate impacts on cities, settlements, infrastructure, supply chains and services due to wildfires, floods, droughts, heatwaves, storms and sea level rise (SLR). For example in New Zealand, extreme snow, heavy rainfall and wind events have combined to impact road networks, power and water supply, interdependent wastewater and stormwater services and business activities (high confidence) {11.3.3, 11.5.1, 11.8.1}.

Key implementation risk

- Inability of institutions and governance systems to manage climate risks. For example the scale and scope of projected climate impacts overwhelm the capacity of institutions, organisations and systems to provide necessary policies, services, resources and coordination to address socioeconomic impacts (high confidence) {11.5.1.2, 11.5.1.3, 11.5.2.3, 11.7.1, 11.7.2, 11.7.3}.

There are important interactions between mitigation and adaptation policies and their implementation (high confidence). Integrated policies in interdependent systems across biodiversity, water quality, water availability, energy, transport, land use and forestry for mitigation can support synergies between adaptation and mitigation. These have co-benefits for the management of land use, water and associated conflicts and for the functioning of cities and settlements. For example, projected increases in fire, drought, pest incursions, storms and wind place forests at risk and affect their ongoing role in meeting New Zealand’s emissions reduction goals. {11.3.4.3, 11.3.10.2, 11.3.5.3, Box 11.5}

Challenges and solutions

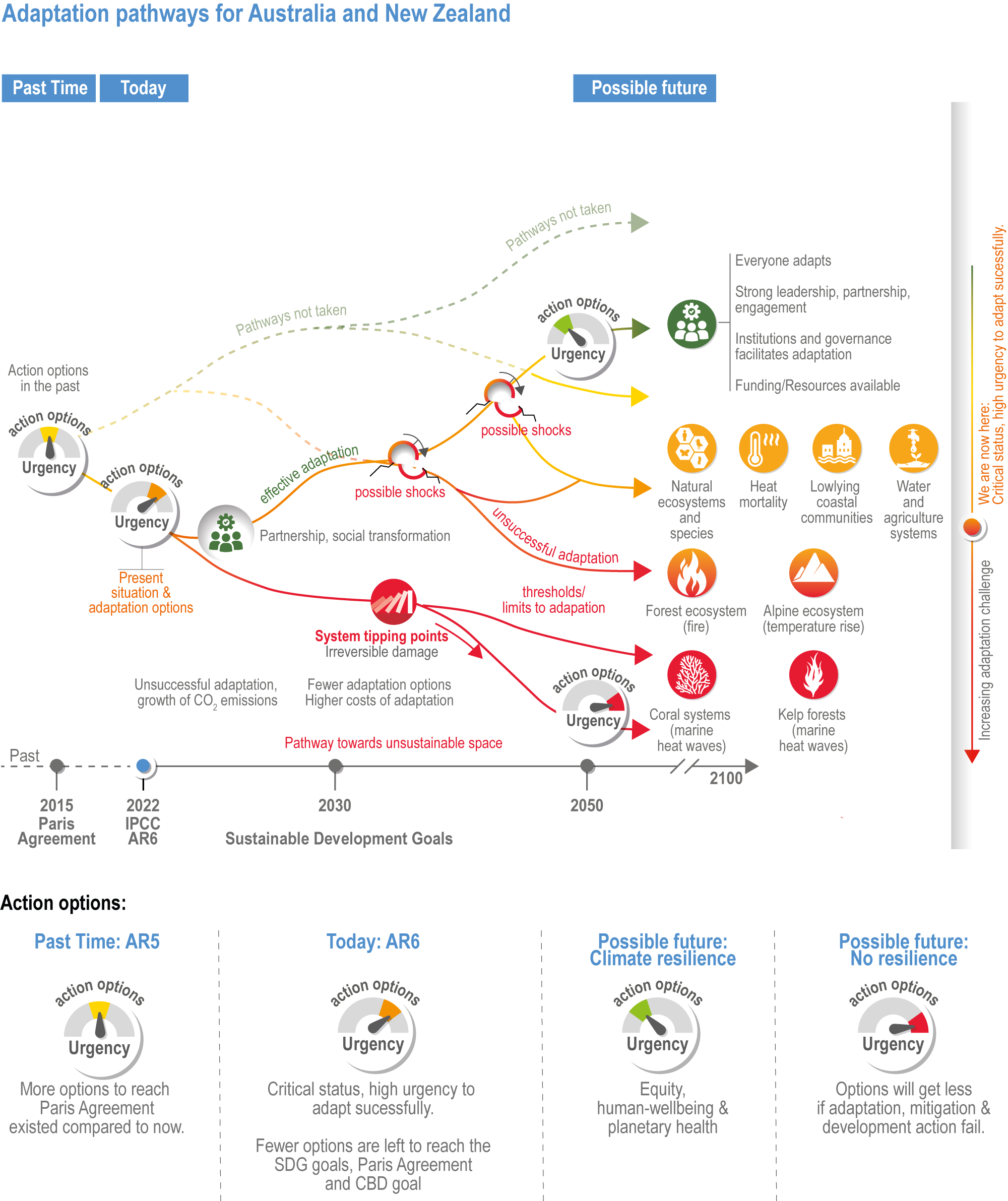

The ambition, scope and progress of the adaptation process have increased across governments, non-government organisations, businesses and communities (high confidence). This process includes vulnerability and risk assessments, identification of strategies and options, planning, implementation, monitoring, evaluation and review. Initiatives include legislated institutional frameworks for risk assessment and national adaptation planning and monitoring in New Zealand, a National Recovery and Resilience Agency and National Disaster Risk Reuction Framework in Australia, deployment of new national guidance, decision tools, collaborative governance approaches and the introduction of climate risk and disclosure regimes for the private sector. The focus, however, has been on adaptation planning, rather than on implementation. {11.5.1, 11.7.1.1, Box 11.6, Table 11.15a, Table 11.15b, Table 11.17}

Adaptation progress is uneven, due to gaps, barriers and limits to adaptation and adaptive capacity deficits (very high confidence). Progress in adaptation planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation is lagging. Barriers include lack of consistent policy direction, competing objectives, divergent risk perceptions and values, knowledge constraints, inconsistent information, fear of litigation, up-front costs and lack of engagement, trust and resources. Adaptation limits are being approached for some species and ecosystems. Adaptive capacity to address the barriers and limits can be built through greater engagement with groups and communities to build trust and social legitimacy through the inclusion of diverse values, including those of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Tangata Whenua Māori. {11.4, 11.5, 11.6, 11.7, 11.8, Table 11.4, Table 11.5, Table 11.6, Table 11.16, Box 11.2}

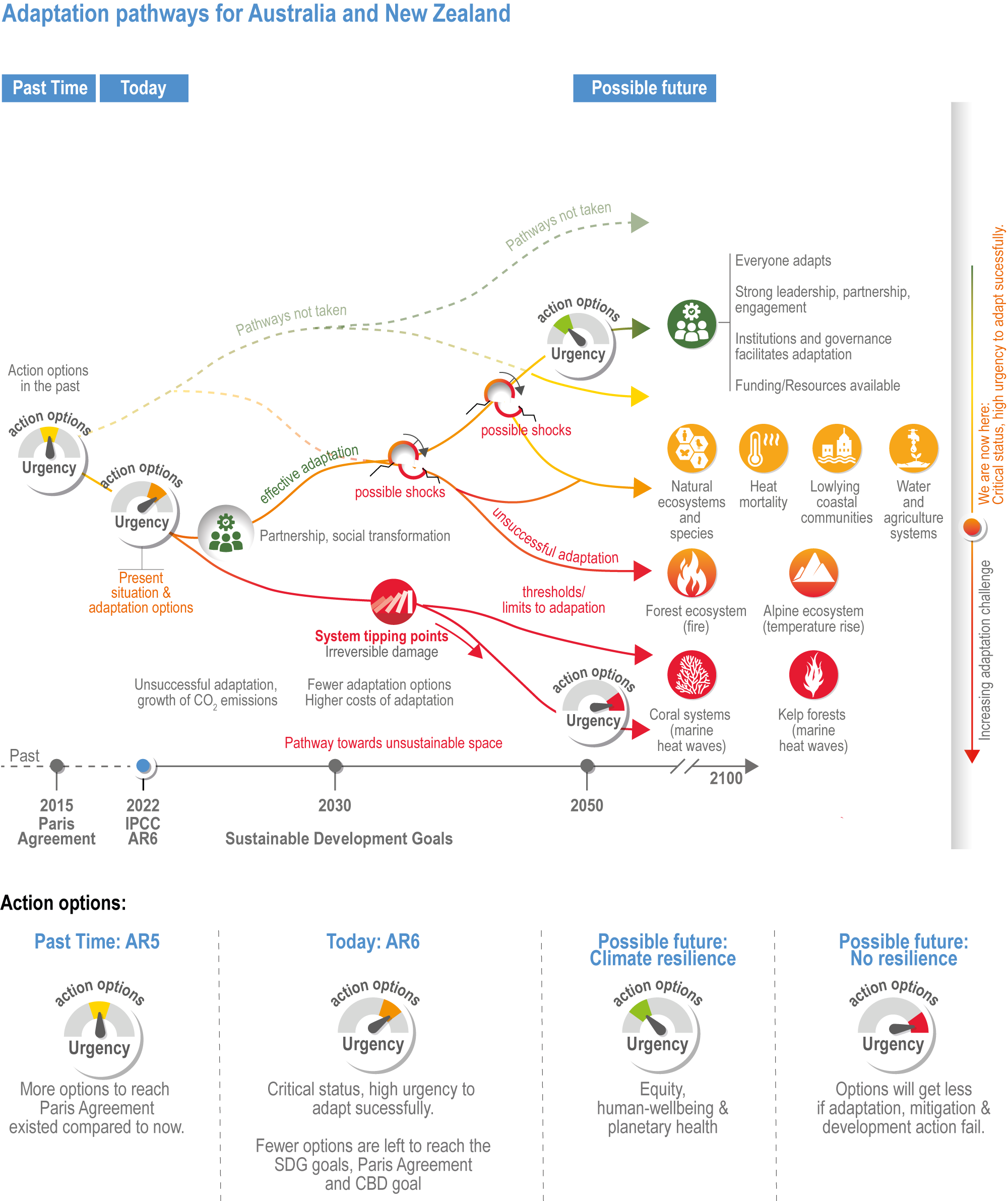

A range of incremental and transformative adaptation options and pathways is available as long as enablers are in place to implement them (high confidence). Key enablers for effective adaptation include shifting from reactive to anticipatory planning, integration and coordination across levels of government and sectors, inclusive and collaborative institutional arrangements, government leadership, policy alignment, nationally consistent and accessible information and decision-support tools, along with adaptation funding and finance, and robust, consistent and strategic policy commitment. Over 75% of people in Australia and New Zealand agree that climate change is occurring and over 60% believe climate change is caused by humans, giving climate adaptation and mitigation action further social legitimacy. {11.7.3, Table 11.17}

New knowledge on system complexity, managing uncertainty and how to shift from reactive to adaptive implementation is critical for accelerating adaptation (high confidence). Priorities include a greater understanding of impacts on natural system dynamics; the exposure and vulnerability of different groups within society, including Indigenous Peoples; the relationship between mitigation and adaptation; the effectiveness and feasibility of different adaptation options; the social transitions needed for transformative adaptation; and the enablers for new knowledge to better inform decision-making (e.g., monitoring data repositories, risk and vulnerability assessments, robust planning approaches, sharing adaptation knowledge and practice). {11.7.3.3}

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Tangata Whenua Māori can enhance effective adaptation t hrough the passing down of knowledge about climate change planning that promotes collective action and mutual support across the region (high confidence). Supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Tangata Whenua Māori institutions, knowledge and values enable self-determination and create opportunities to develop adaptation responses to climate change. Actively upholding the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Māori interests under the Treaty of Waitangi at all levels of government enables intergenerational approaches for effective adaptation. {11.3, 11.4, 11.6, 11.7.3; Cross-Chapter Box INDIG in Chapter 18}

A step change in adaptation is needed to match the rising risks and to support climate resilient development (very high confidence). Current adaptation is largely incremental and reactive. A shift to transformative and proactive adaptation can contribute to climate resilient development. The scale and scope of cascading, compounding and aggregate impacts require new, larger-scale and timely adaptation. Monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of adaptation progress and continual adjustment is critical. The transition to climate resilient development pathways can generate major co-benefits, but complex interactions between objectives can create trade-offs. {11.7, 11.8.1, 11.8.2}

Delay in implementing adaptation and emission reductions will impede climate resilient development, resulting in more costly climate impacts and greater scale of adjustments (very high confidence). The region faces an extremely challenging future. Reducing the risks would require significant and rapid emission reductions to keep global warming to 1.5°C–2.0°C, as well as robust and timely adaptation. The projected warming under current global emissions reduction policies would leave many of the region’s human and natural systems at very high risk and beyond adaptation limits. {11.8, Table 11.1, Table 11.14, Figure 11.6}

11.1 Introduction

This chapter assesses the observed impacts, projected risks, vulnerability and adaptation, and the implications for climate resilient development for the Australasia region, based on the literature published up to 1 September 2021. It should be read in conjunction with other Working Group (WG) II chapters, the climate science assessment in the WGI report and the greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation assessment in the WGIII report.

11.1.1 Context

The Australasia region is defined as the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and territories of Australia and New Zealand. In both countries, climate adaptation is largely implemented at a sub-national level through the devolution of functions constitutionally or by statute, alongside disaster risk reduction (COAG, 2011; Lawrence et al., 2015; Macintosh et al., 2015).

Australia’s economy is dominated by financial and insurance services, education, mining, construction, tourism, health care and social assistance (ABS, 2018) with Australian exports accruing mostly from mining (ABS, 2018; ABS, 2019). In New Zealand, service industries, including tourism, collectively account for around two-thirds of GDP (NZ Treasury, 2016). The primary sector contributes 6% of New Zealand’s GDP and over half of the country’s export earnings (NZ Treasury, 2016).

Existing vulnerabilities expose and exacerbate inequalities between rural, regional and urban areas, Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples, those with health and disability needs, and between generations, incomes and health status, increasing the relative climate change risk faced by some groups and places (high confidence) (Jones et al., 2014; Bertram, 2015; Perry, 2017; Hazledine and Rashbrooke, 2018).

Previous IPCC reports (Table 11.1) have documented observed climate impacts, projected risks, adaptation challenges and opportunities. This chapter presents more evidence of observed climate impacts and adaptation, better quantification of socioeconomic risks, new information about cascading and compounding risks, greater emphasis on adaptation enablers and barriers, and links to climate resilient development.

Table 11.1 | Summary of key conclusions from the IPCC 5th Assessment Report (AR5) Australasia chapter (Reisinger et al., 2014) and relevant conclusions from the IPCC Special Reports on Global Warming of 1.5°C (IPCC, 2018), Climate Change and Land (IPCC, 2019a) and Oceans and Cryosphere (IPCC, 2019b).

Conclusions | Report |

Our regional climate is changing (very high confidence) and warming will continue through the 21st century (virtually certain) with more hot days, fewer cold days, less snow, less rainfall in southern Australia and the northeast of both of New Zealand’s islands, more rainfall in western New Zealand, more extreme rainfall, SLR, increased fire weather in southern Australia and across New Zealand and fewer cyclones but a greater proportion of intense cyclones. | |

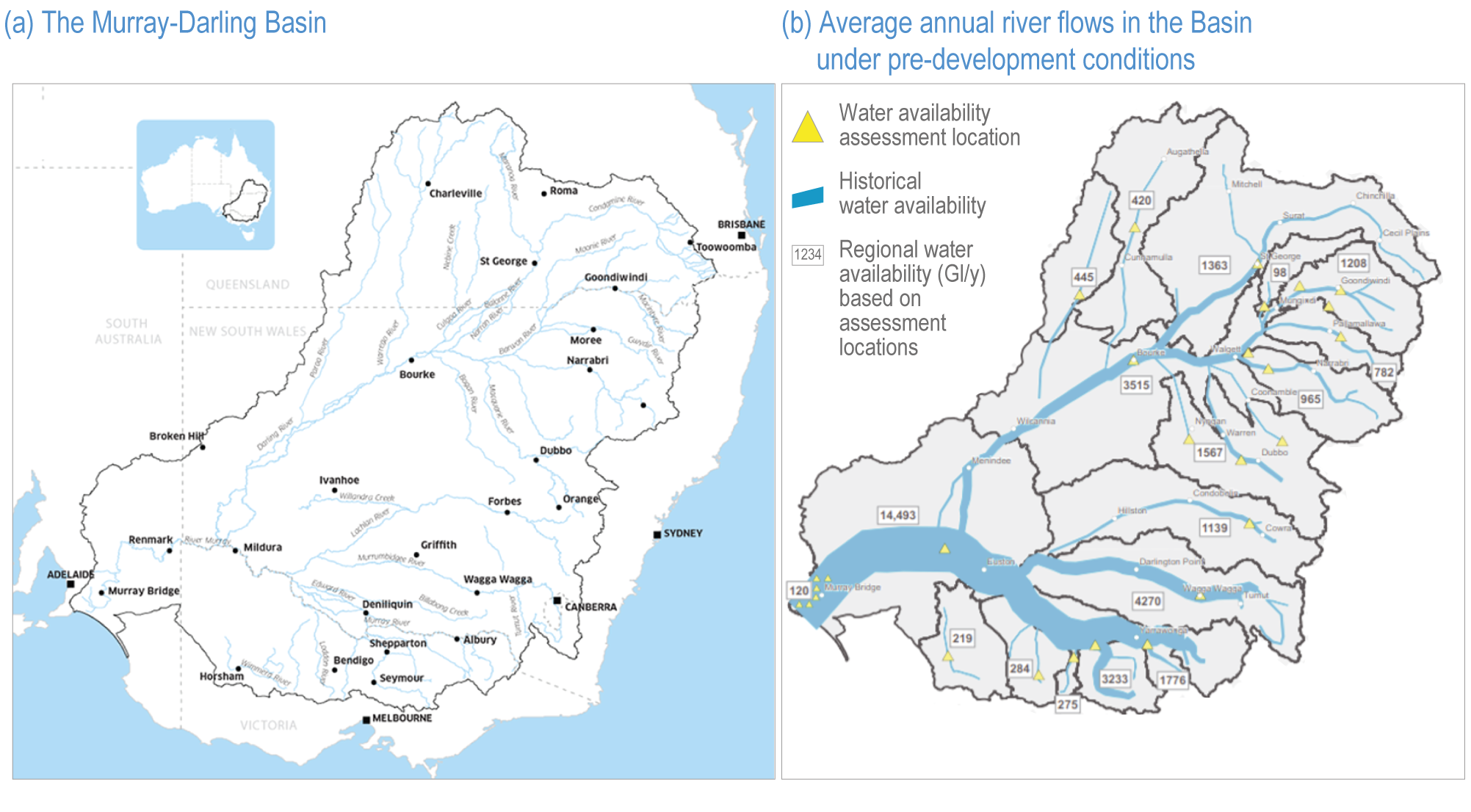

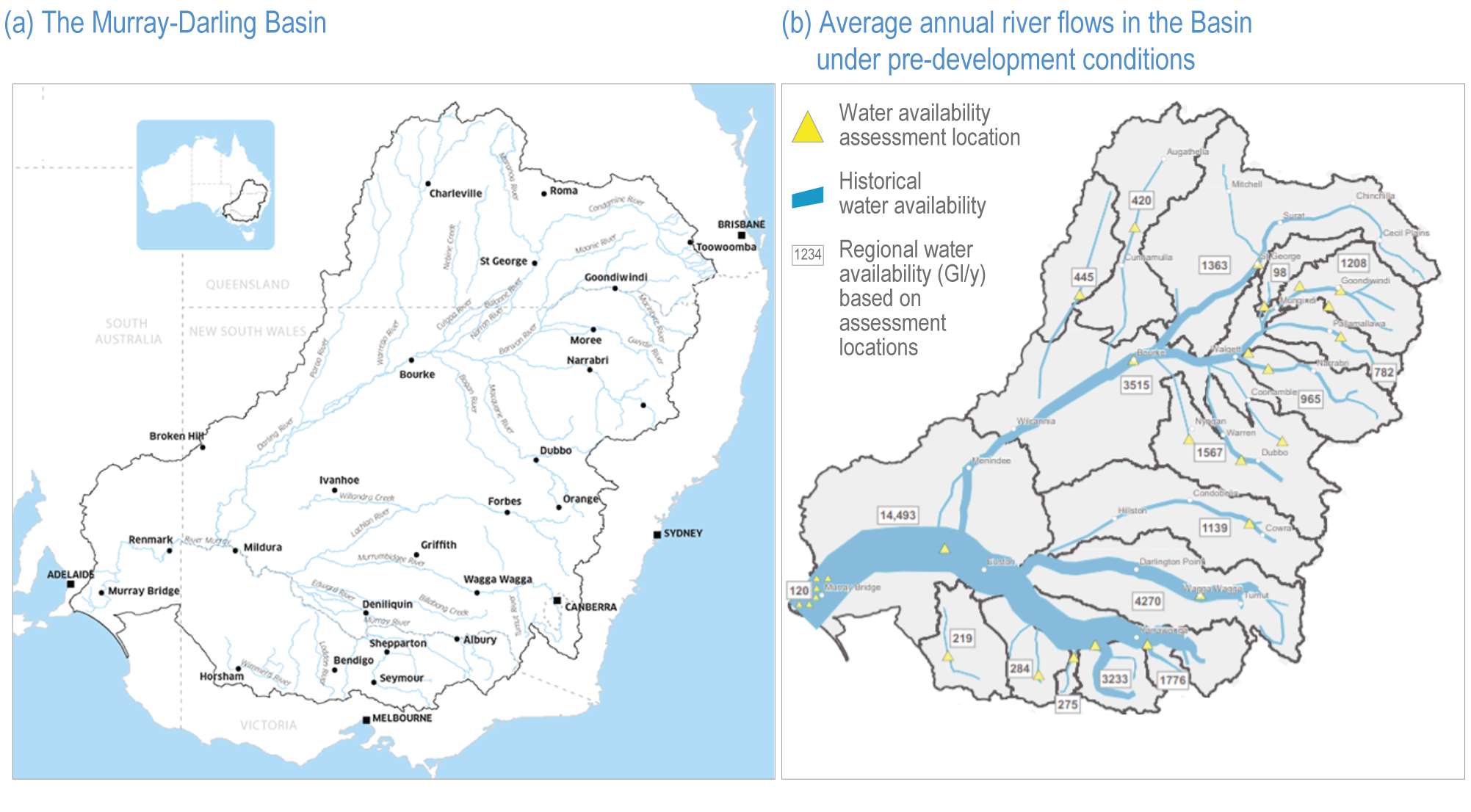

Key risks include changes in the structure and composition of Australian coral reefs, loss of montane ecosystems, increased flood damage, reduced water resources in southern Australia, more deaths and infrastructure damage during heatwaves, more fire-related impacts on ecosystems and settlements in southern Australia and across New Zealand, greater risk to coastal infrastructure and ecosystems and reduced water availability in the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) and southern Australia (high confidence). Benefits are projected for some sectors and locations (high confidence), including reduced winter mortality and energy demand for heating, increased forest growth and enhanced pasture productivity. | |

Adaptation is occurring and becoming mainstreamed in some planning processes (high confidence). Adaptive capacity is considered generally high in many human systems, but adaptation implementation faces major barriers, especially for transformational responses (high confidence). Some synergies and trade-offs exist between different adaptation responses and between mitigation and adaptation, with interactions occurring both within and outside the region (very high confidence). | |

Vulnerability remains uncertain due to incomplete consideration of socioeconomic dimensions (very high confidence), including governance, institutions, patterns of wealth and ageing, access to technology and information, labour force participation and societal values. | |

Emissions reductions under Nationally Determined Contributions from signatories to the Paris Agreement are consistent with a global warming of 2.5°C–3.0°C above pre-industrial temperatures by 2100. Much deeper emission reductions are needed prior to 2030 to limit warming to 1.5°C. There are limits to adaptation and adaptive capacity for some human and natural systems at global warming of 1.5°C, with associated losses. | |

Climate impacts will disproportionately affect the welfare of impoverished and vulnerable people because they lack adaptation resources. Strengthening the climate-action capacities of national and sub-national authorities, civil society, the private sector, Indigenous People and local communities can support implementation of actions. | |

Land-related responses that contribute to climate change adaptation and mitigation can also combat desertification and land degradation and enhance food security. | |

Appropriate design of policies, institutions and governance systems at all scales can contribute to land-related adaptation and mitigation while facilitating the pursuit of climate-adaptive development pathways. | |

Mutually supportive climate and land policies have the potential to save resources, amplify social resilience, support ecological restoration and foster collaboration between stakeholders. | |

Near-term action to address climate change adaptation and mitigation, desertification, land degradation and food security can bring social, ecological, economic and development co-benefits. Delaying action (both mitigation and adaptation) will be more costly. | |

The rate of global mean SLR of 3.6 mm yr −1 for 2006–2015 is unprecedented over the last century. Extreme wave heights, coastal erosion and flooding have increased in the Southern Ocean by around 1.0 cm yr −1 over the period 1985–2018. | |

Some species of plants and animals have increased in abundance, shifted their range and established in new areas as glaciers receded and the snow-free season lengthened. Some cold-adapted or snow-dependent species have declined in abundance, increasing their risk of extinction, notably on mountain summits. | |

Many marine species have shifted their range and seasonal activities. Altered interactions between species have caused cascading impacts on ecosystem structure and functioning. | |

Mean SLR projections are higher by 0.1 m compared to AR5 under RCP8.5 in 2100. Extreme sea level events that are historically rare (once per century) are projected to occur frequently (at least once yr −1) at many locations by 2050. | |

Projected ecosystem responses include losses of species habitat and diversity and degradation of ecosystem functions. Warm water corals are at high risk already and are projected to transition to very high risk even if global warming is limited to 1.5°C. | |

Governance arrangements (e.g., marine protected areas, spatial plans and water management systems) are too fragmented across administrative boundaries and sectors to provide integrated responses to the increasing and cascading risks. Financial, technological, institutional and other barriers exist for implementing responses. | |

Enabling climate resilience and sustainable development depends critically on urgent and ambitious emissions reductions coupled with coordinated, sustained and increasingly ambitious adaptation actions. This includes better cooperation and coordination among governing authorities, education and climate literacy, sharing of information and knowledge, finance, addressing social vulnerability and equity, and institutional support. |

11.1.2 Economic, Demographic and Social Trends

Economic, demographic and sociocultural trends influence the exposure, vulnerability and adaptive capacity of individuals and communities (high confidence) (Elrick-Barr et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2016; Hayward, 2017; B. Frame et al., 2018; Plummer et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2018; Gartin et al., 2020). In the absence of proactive adaptation, climate change impacts are projected to worsen inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples and other vulnerable groups (Green et al., 2009; Manning et al., 2014; Ambrey et al., 2017) (high confidence). Socioeconomic inequality, low incomes and high levels of debt, poor health and disabilities increase vulnerability and limit adaptation (Hayward, 2012) (11.7.2). A lack of services, such as schools and medical services, in poorer and rural areas and decision-making processes that privilege some voices over others exacerbate inequalities (Kearns et al., 2009; Hinkson and Vincent, 2018).

Changes to the composition and location of different demographic groups in the region contribute to increased exposure or vulnerability to climate change (medium confidence). Australia’s population reached 25 million in 2018 and is projected to grow to 37.4–49.2 million by 2066, with most growth in major cities (accounting for 81% of Australia’s population growth from 2016 to 2017) (ABS, 2018), although COVID-19 is expected to slow the growth rate (CoA, 2020c). The highest growth rates outside of major cities occurred mostly in coastal regions (ABS, 2017), which have built assets exposed to sea level rise (SLR). New Zealand’s population was 5.1 million at the end of 2020 and is projected to increase to 6.0–6.5 million by 2068, assuming no marked changes in migration patterns (Stats NZ, 2016; Stats NZ, 2021). Although the population densities of both countries are much lower than other OECD countries, they are highly urbanised with over 86% living in urban areas in both countries (Productivity Commission, 2017; World Bank, 2018). This proportion is projected to increase to over 90% by 2050 (UN DESA, 2019) mostly in coastal areas (Rouse et al., 2017). Consideration of climate change impacts when planning and managing such growth and associated infrastructure could help avoid new vulnerabilities being created, particularly from wildfires, sea level rise (SLR), heat stress and flooding.

The region has an increasingly diverse population through the arrival of migrants, including those from the Pacific, whose innovations, skills and transnational networks enhance their and others’ adaptive capacity (De et al., 2016; Fatorić et al., 2017; Barnett and McMichael, 2018), although language barriers and socioeconomic disadvantage can create vulnerabilities for some (11.7.2).

Climate change inaction exacerbates intergenerational inequity, including prospects for the current younger population (Hayward, 2012). Increasing transient worker populations (ABS, 2018) may diminish social networks and adaptive capacity (Jiang et al., 2017). The region has an ageing population and increasing numbers of people living on their own who are highly vulnerable to extreme events, including heat stress and flooding (Zhang et al., 2013).

Socioeconomic trends are affected by global mega trends (KPMG, 2021), which are expected to influence the region’s ability to implement climate change adaptation strategies (World Economic Forum, 2014). Digital technological advances have potential benefits for building adaptive capacity (Deloitte, 2017a).

11.2 Observed and Projected Climate Change

11.2.1 Observed Climate Change

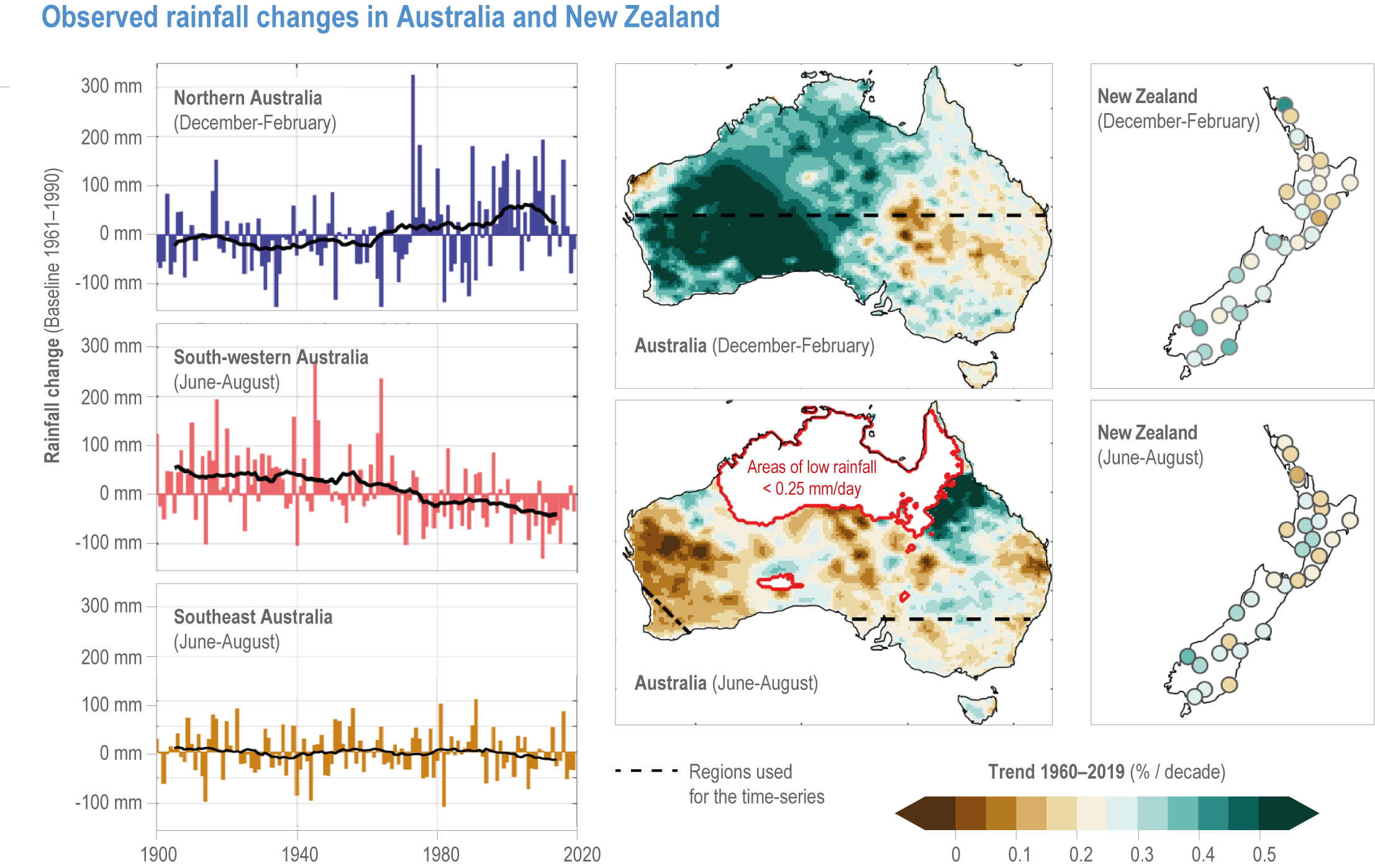

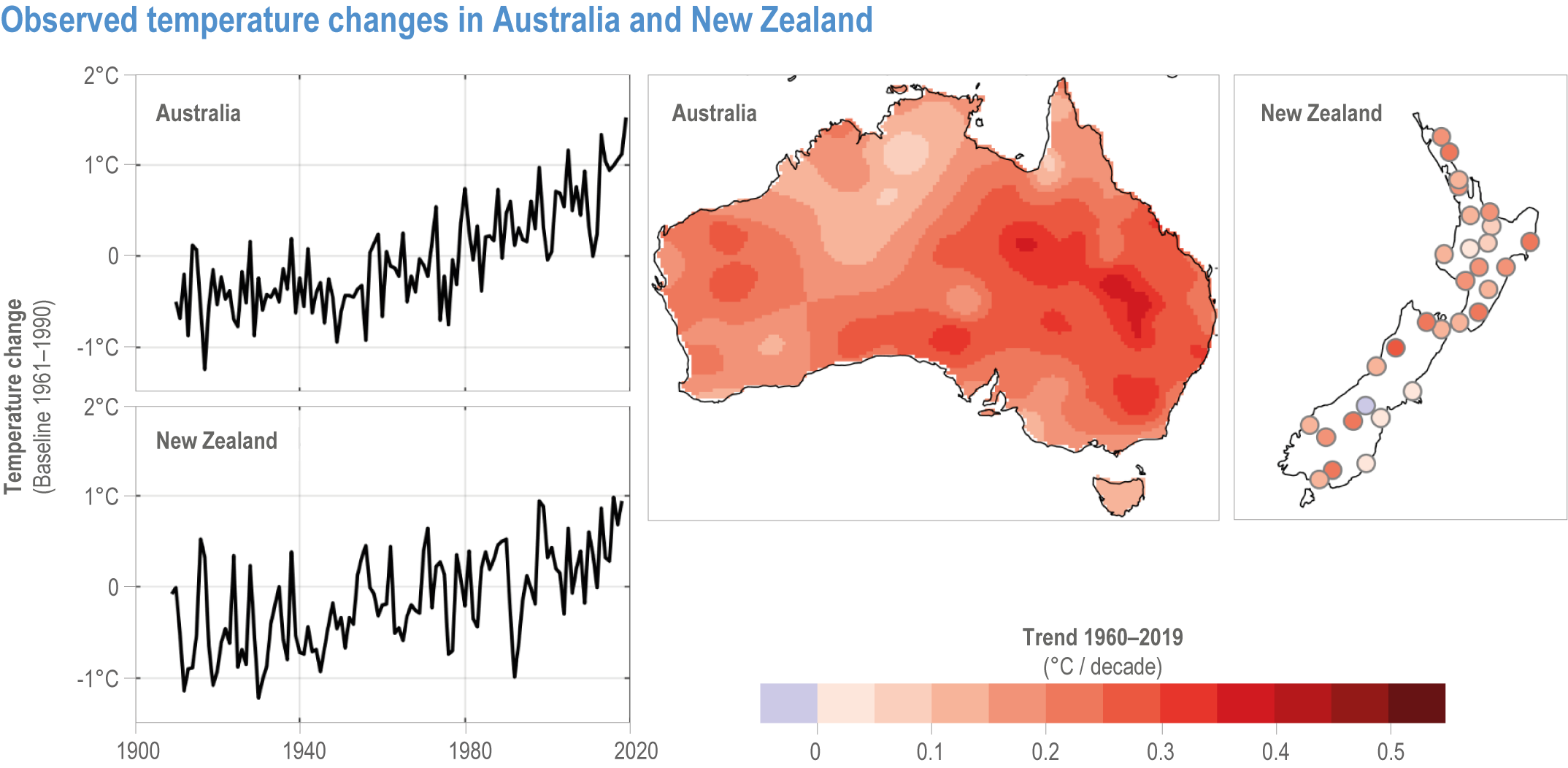

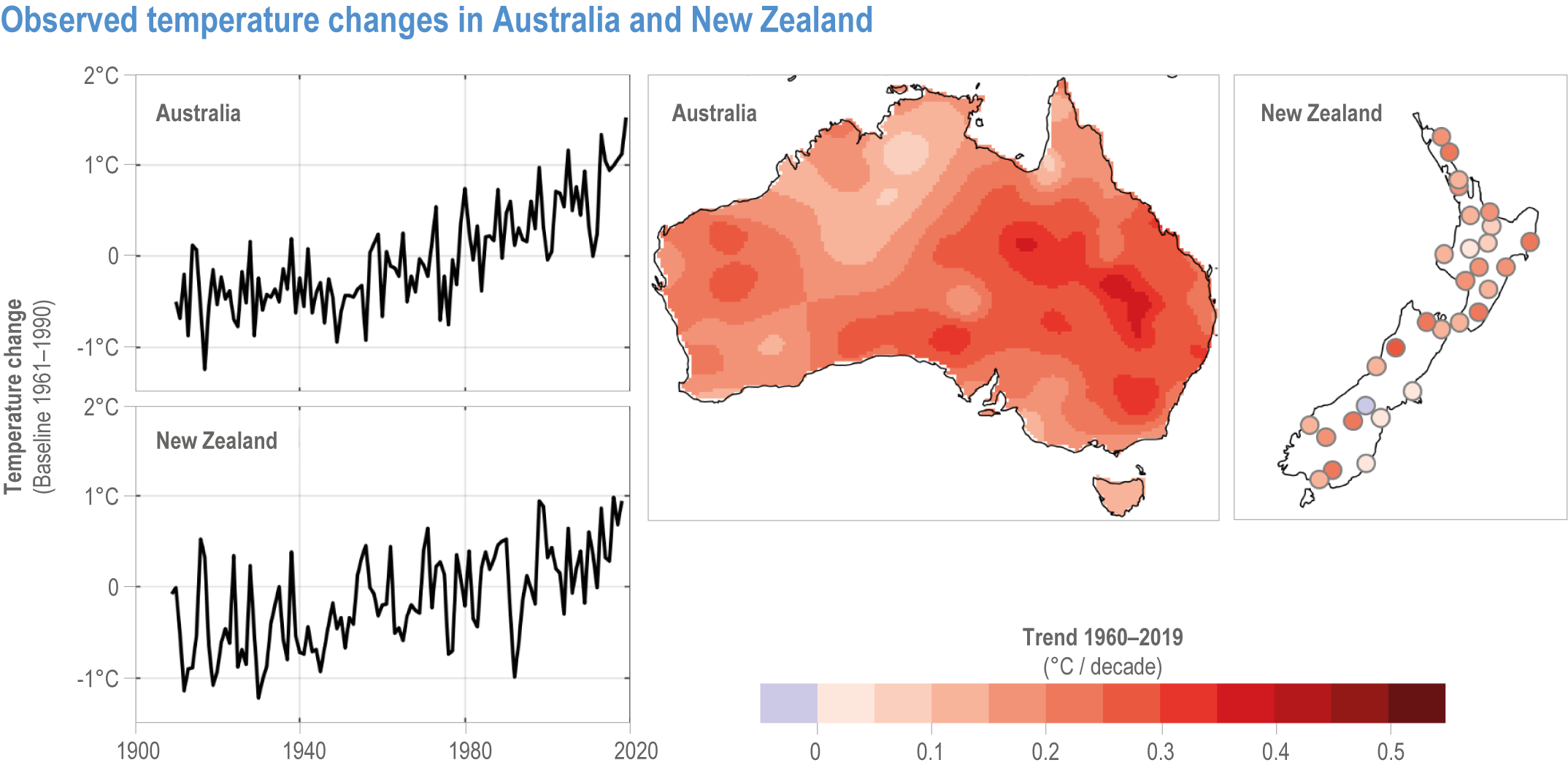

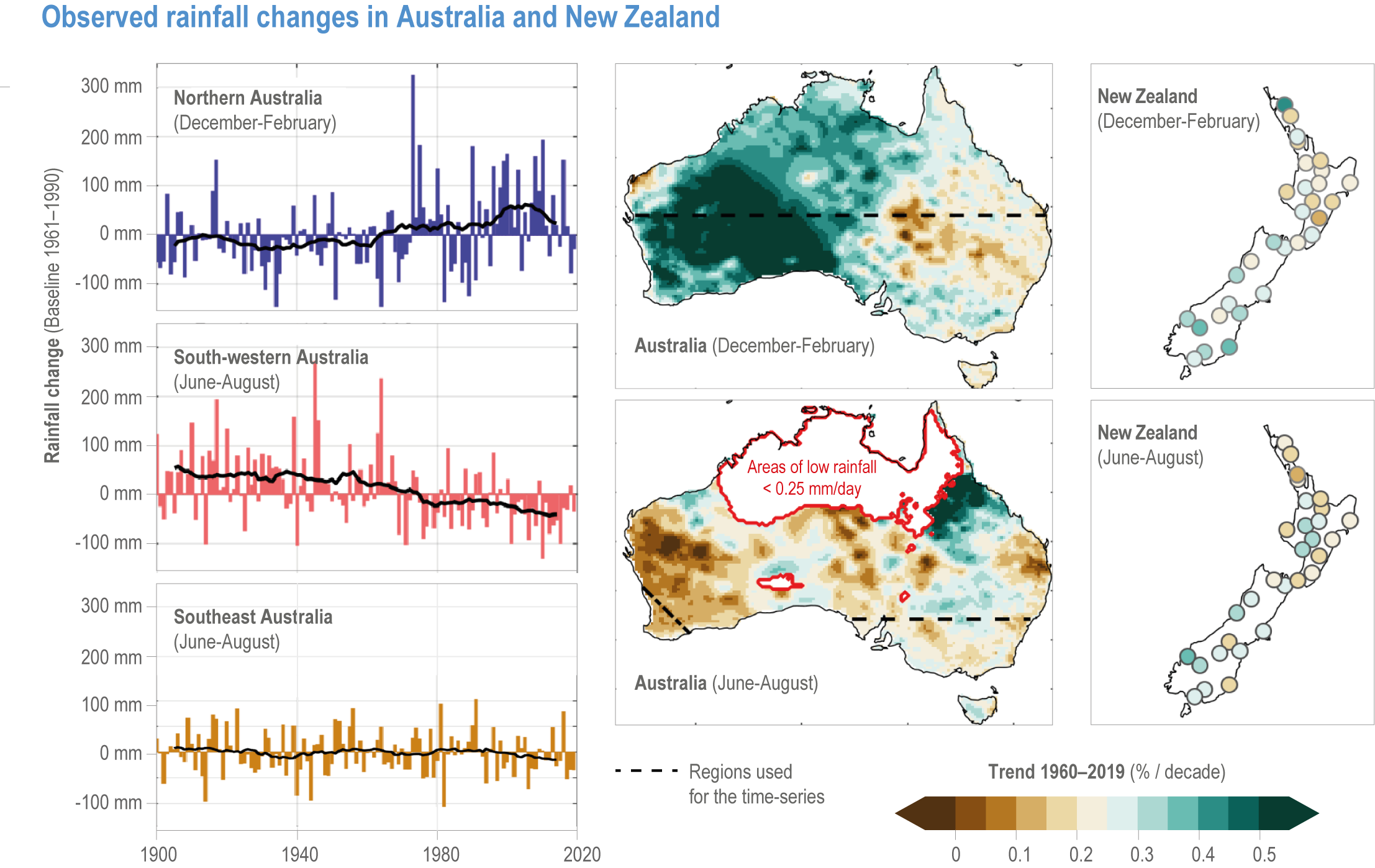

Regional climate change has continued since AR5 was released in 2014, with trends exacerbating many extreme events (very high confidence). The following changes are quantified with references in Tables 11.2a and 11.2b. The region has continued to warm (Figure 11.1), with more extremely high temperatures and fewer extremely low temperatures. Snow depths and glacier volumes have declined. Sea level rise and ocean acidification have continued. Northern Australia has become wetter, while April–October rainfall has decreased in south-western and south-eastern Australia. In New Zealand, most of the south has become wetter, while most of the north has become drier (Figure 11.2). The frequency, severity and duration of extreme fire weather conditions have increased in southern and eastern Australia and eastern New Zealand. Changes in extreme rainfall are mixed. There has been a decline in tropical cyclone frequency near Australia.

Figure 11.1 | Observed temperature changes in Australia and New Zealand. Annual temperature change time series are shown for 1910–2019. Mean annual temperature trend maps are shown for 1960–2019 using contours for Australia and individual sites for New Zealand. Data courtesy of BOM and NIWA.

Figure 11.2 | Observed rainfall changes in Australia and New Zealand. Rainfall change time series for 1900–2019 are shown for Northern Australia (December–February: DJF), southwest Australia (June–August: JJA) and southeast Australia (JJA). Dashed lines on the maps for Australia show regions used for the time series. Rainfall trend maps are shown for 1960–2019 (DJF and JJA) using contours for Australia and individual sites for New Zealand. Areas of low Australian rainfall (less than 0.25 mm/day) are shaded white in JJA. Data courtesy of BOM and NIWA.

Reliable measurements are limited for some types of storms, particularly thunderstorms, lightning, tornadoes and hail (Walsh et al., 2016). Many high-impact events are a combination of interacting physical processes across multiple spatial and temporal scales (e.g., fires, heatwaves and droughts), and better understanding of these extreme and compound events is needed (Zscheischler et al., 2018).

Some of the observed trends and events can be partly attributed to anthropogenic climate change, as documented in Chapter 16. Examples include regional warming trends and sea level rise (SLR), terrestrial and marine heatwaves, declining rainfall and increasing fire weather in southern Australia and extreme rainfall and severe droughts in New Zealand.

11.2.2 Projected Climate Change

There are three main sources of uncertainty in climate projections: emission scenarios, regional climate responses and internal climate variability (CSIRO and BOM, 2015). Emission scenario uncertainty is captured in Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) for greenhouse gases and aerosols. RCP2.6 represents low emissions, RCP4.5 medium emissions and RCP8.5 high emissions. Regional climate response uncertainty and internal climate variability uncertainty are captured in climate model simulations driven by the RCPs.

Further climate change is inevitable, with the rate and magnitude largely dependent on the emission pathway (very high confidence) (IPCC, 2021). Preliminary projections based on Climate Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models are described in the IPCC Working Group I Atlas. For Australia, the CMIP6 projections broadly agree with CMIP5 projections except for a group of CMIP6 models with greater warming and a narrower range of summer rainfall change in the north and winter rainfall change in the south (Grose et al., 2020). For New Zealand, the CMIP6 projections are similar to CMIP5, but the CMIP6 models indicate greater warming, a smaller increase in summer precipitation and a larger increase in winter precipitation (Gutiérrez et al., 2021).

Dynamical and statistical downscaling offer the prospect of improved representation of regional climate features and extreme weather events (IPCC 2021: Working Group I Chapter 10 (Doblas-Reyes et al., 2021)), but the added value of downscaling is complex to evaluate (Ekström et al., 2015; Rummukainen, 2015; Virgilio et al., 2021). Downscaled simulations are available for New Zealand (MfE, 2018) and various Australian regions (Gutiérrez et al., 2021). Further downscaling was recommended by the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements (CoA, 2020e). Projections for rainfall, thunderstorms, hail, lightning and tornadoes have large uncertainties (Walsh et al., 2016; MfE, 2018).

Future changes in climate variability are affected by the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Southern Annular Mode (SAM), Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO). An increase in strong El Niño and La Niña events is projected (Cai, 2015), along with more extreme positive phases of the IOD (Cai et al., 2018) and a positive trend in SAM (Lim et al., 2016), but potential changes in the IPO are unknown (NESP ESCC, 2020). There is uncertainty about regional climate responses to projected changes in ENSO (King et al., 2015; Perry et al., 2020; Virgilio et al., 2021).

Australian climate projections are quantified with references in Table 11.3a. Further warming is projected, with more hot days, fewer cold days, reduced snow cover, ongoing sea level rise (SLR) and ocean acidification (very high confidence). Winter and spring rainfall and soil moisture are projected to decrease, with higher evaporation rates, decreased wind over southern mainland Australia, increased wind over Tasmania, and more extreme fire weather in southern and eastern Australia (high confidence). Heavy rainfall intensity is projected to increase, with more droughts over southern and eastern Australia (medium confidence). Increased winter rainfall is projected over Tasmania, with decreased rainfall in southwestern Victoria in autumn and in western Tasmania in summer, fewer tropical cyclones with a greater proportion of severe cyclones and decreased soil moisture in the north (medium confidence). Hailstorm frequency may increase (low confidence).

Table 11.3a | Projected climate change for Australia. Projections are given for different RCPs (RCP2.6 is low, RCP4.5 is medium, RCP8.5 is high) and years (e.g., 20-year period centred on 2090). Uncertainty ranges are generally 10th–90th percentile, and median projections are given in square brackets where possible. The four Australian regions are shown in Chapter 2 of (CSIRO and BOM, 2015). Preliminary projections based on CMIP6 models are included for some climate variables from the IPCC (2021) WGI report.

Climate variable | Projected change (year, RCP) relative to 1986–2005 | References |

Air temperature | Annual mean temperature

| |

Sea surface temperature |

| |

Air temperature extremes |

| |

Rainfall | Annual mean rainfall

| |

Rainfall extremes | Intensity of daily total rain with 20-year recurrence interval

| |

Drought | Time in drought (Standardised Precipitation Index below −1)

| |

Wind speed | 0–5% decrease over southern mainland Australia and 0–5% increase over Tasmania (2090, RCP8.5) | |

Sea level rise |

These projections have not been updated to include an Antarctic dynamic ice sheet factor which increased global sea level projections for RCP8.5 by approx. 10 cm. Preliminary CMIP6 projections indicate +40–50 cm (2090, SSP1-RCP2.6) and +70–90 cm (2090, SSP5-RCP8.5) | |

Sea level extremes | Increase in the allowance for a storm tide event with 1% annual exceedance probability (100-year return period)

| |

Fire |

| (Clarke and Evans, 2019; Dowdy et al., 2019; Virgilio et al., 2019; Clarke et al., 2020; NESP ESCC, 2020; Clark et al., 2021) |

Tropical cyclones and other storms |

| |

Snow and ice |

| (Bhend et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2016; Di Luca et al., 2018) |

Ocean acidification | pH is projected to drop by about 0.1 (2090, RCP2.6) to 0.3 (2090, RCP8.5) |

New Zealand climate projections are quantified with references in Table 11.3b. Further warming is projected, with more hot days, fewer cold days, less snow and glacial ice, ongoing sea level rise (SLR) and ocean acidification (very high confidence). Increases in winter and spring rainfall are projected in the west of the North and South Islands, with drier conditions in the east and north, caused by stronger westerly winds (medium confidence). In summer, wetter conditions are projected in the east of both islands, with drier conditions in the west and central North Island (medium confidence). Fire weather indices are projected to increase over northern and eastern New Zealand (medium confidence). Heavy rainfall intensity is projected to increase over most regions, with increased extreme wind speeds in eastern regions, especially in Marlborough and Canterbury, and reduced relative humidity almost everywhere, except for the west coast in winter (medium confidence). Drought frequency may increase in the north (medium confidence).

11.3 Observed Impacts, Projected Impacts and Adaptation

This section assesses observed impacts, projected risks and adaptation for 10 sectors and systems. Boxes provide more details on specific issues. Risk is considered in terms of vulnerability, hazards (impact driver), exposure, reasons for concern and complex and cascading risks (Chapter 1; Figure 1.2).

11.3.1 Terrestrial and Freshwater Ecosystems

11.3.1.1 Observed Impacts

Widespread and severe impacts on ecosystems and species are now evident across the region (very high confidence) (Table 11.4). Climate impacts reflect both ongoing change and discrete extreme weather events (Harris et al., 2018), and the climatic change signal is emerging despite confounding influences (Hoffmann et al., 2019). Fundamental shifts are observed in the structure and composition of some ecosystems and associated services (Table 11.4). Impacts documented for species include global and local extinctions, severe regional population declines and phenotypic responses (Table 11.4). In terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, land use impacts are interacting with climate, resulting in significant changes to ecosystem structure, composition and function (Bergstrom et al., 2021), with some landscapes experiencing catastrophic impacts (Table 11.4). Some of the observed changes may be irreversible where projected impacts on ecosystems and species persist (Table 11.5). Of note is the global extinction of an endemic mammal species, the Bramble Cay melomys (Melomys rubicola), from the loss of habitat attributable in part to sea level rise (SLR) and storm surges in the Torres Strait (Table 11.4).

Natural forest and woodland ecosystem processes are experiencing differing impacts and responses depending on the climate zone (high confidence). In Australia, an overall increase in the forest fire danger index, associated with warming and drying trends (Table 11.2a), has been observed particularly for southern and eastern Australia in recent decades (Box 11.1). The 2019–2020 mega wildfires of south eastern Australia burnt between 5.8 and 8.1 million hectares of mainly temperate broadleaf forest and woodland, but with substantial areas of rainforest also impacted, and were unprecedented in their geographic location, spatial extent and forest types burnt (Boer et al., 2020; Nolan et al., 2020; Abram et al., 2021; Collins et al., 2021; Godfree et al., 2021). The human influence on these events is evident (Abram et al., 2021; van Oldenborgh et al., 2021) (Box 11.1). The fires had significant consequences for wildlife (Hyman et al., 2020; Nolan et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2020) (Box 11.1) and flow-on impacts for aquatic fauna (Silva et al., 2020). In southern Australia, deeply rooted native tree species can access soil and groundwater resources during drought, providing a level of natural resilience (Bell and Nikolaus Callow, 2020; Liu et al., 2020). However, the Northern Jarrah forests of south western Australia have experienced tree mortality and dieback from long-term precipitation decline and acute heatwave-compounded drought (Wardell-Johnson et al., 2015; Matusick et al., 2018). While there is limited information on observed impacts for New Zealand, increased mast seeding events in beech forest ecosystems that stimulate invasive population irruptions have been recorded (Schauber et al., 2002; Tompkins et al., 2013).

Table 11.2a | Observed climate change for Australia.

Climate variable | Observed change | References |

Air temperature over land | Increased by 1.4°C from 1910 to 2019, with 2019 being the warmest year; 9 of the 10 warmest on record have occurred since 2005; clear anthropogenic attribution. | (BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ; Trewin et al., 2020; BoM, 2021a; Gutiérrez et al., 2021) |

Sea surface temperature | Increased by 1.0°C from 1900 to 2019 (0.09°C/decade), with an increase of 0.16°C–0.20°C/decade since 1950 in the southeast. Eight of the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 2010. | |

Air temperature extremes over land | More extremely hot days and fewer extremely cold days in most regions. Weaker warming trends in minimum temperatures in southeast Australia compared to elsewhere during 1960–2016. Frost frequency in southeast and southwest Australia has been relatively unchanged since the 1980s. Very high monthly maximum or minimum temperatures that occurred around 2% of the time in the past (1960–1989) now occur 11–12% of the time (2005–2019). Multi-day heatwave events have increased in frequency and duration across many regions since 1950. In 2019, the national average maximum temperature exceeded the 99th percentile on 43 days (more than triple the number in any of the years prior to 2000) and exceeded 39°C on 33 days (more than the number observed from 1960 to 2018 combined). | (Perkins-Kirkpatrick et al., 2016; Alexander and Arblaster, 2017; Pepler et al., 2018; BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ; Perkins-Kirkpatrick and Lewis, 2020; Trancoso et al., 2020) |

Sea temperature extremes | Intense marine heatwave in 2011 near western Australia (peak intensity 4°C, duration 100 days). The likelihood of an event of this duration is estimated to be about five times higher than under pre-industrial conditions. Marine heatwave over northern Australia in 2016 (peak intensity 1.5°C, duration 200 days). Marine heatwave in the Tasman Sea and around southeast mainland Australia and Tasmania from September 2015 to May 2016 (peak intensity 2.5°C, duration 250 days)—likelihood of an event of this intensity and duration has increased about 50-fold. Marine heatwave in the Tasman Sea from November 2017 to March 2018 (peak intensity 3°C, duration 100 days). Marine heatwave on the GBR in 2020 (peak intensity 1.2°C, duration 90 days) | (BoM and CSIRO, 2018 ; BoM, 2020; Laufkötter et al., 2020; Oliver et al., 2021) |

Rainfall | Northern Australian rainfall has increased since the 1970s, with an attributable human influence. April to October rainfall has decreased 16% since the 1970s in southwestern Australia (partly due to human influence) and 12% from 2000–2019 in south-eastern Australia. The lowest recorded average rainfall in Australia occurred in 2019. | (Delworth and Zeng, 2014; Knutson and Zeng, 2018; Dey et al., 2019; BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ; BoM, 2021a) |

Rainfall extremes | Hourly extreme rainfall intensities increased by 10–20% in many locations between 1966 to1989 and 1990 to 2013. Daily rainfall associated with thunderstorms increased 13–24% from 1979 to 2016, particularly in northern Australia. Daily rainfall intensity increased in the northwest from 1950 to 2005 and in the east from 1911 to 2014 and decreased in the southwest and Tasmania from 1911 to 2010. | (Donat et al., 2016; Alexander and Arblaster, 2017; Evans et al., 2017; Guerreiro et al., 2018; Dey et al., 2019; BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ; Bruyère et al., 2020; Dowdy, 2020; Dunn et al., 2020; Gutiérrez et al., 2021) |

Drought | Major Australian droughts occurred in 1895–1902, 1914–1915, 1937–1945, 1965–1968, 1982–1983, 1997–2009 and 2017–2019. Fewer droughts have occurred across most of northern and central Australia since the 1970s, and more droughts have occurred in the southwest since the 1970s; drought trends in the southeast have been mixed since the late 1990s. | (Gallant et al., 2013; Delworth and Zeng, 2014; Alexander and Arblaster, 2017; Dai and Zhao, 2017; Knutson and Zeng, 2018; Dey et al., 2019; Spinoni et al., 2019; Dunn et al., 2020; Rauniyar and Power, 2020; BoM, 2021b; Seneviratne et al., 2021) |

Wind speed | Wind speed decreased 0.067 m/s/decade over land in the period 1941–2016, with a decrease of 0.062 m/s/decade over land from 1979 to 2015, and a decrease of 0.05–0.10 m/s/decade over land from 1988 to 2019. Wind speed increased 0.02 m/s/year across the Southern Ocean during 1985–2018. | (Troccoli et al., 2012; Young and Ribal, 2019; Blunden and Arndt, 2020; Azorin-Molina et al., 2021) |

Sea level rise | Relative SLR was 3.4 mm/year from 1993 to 2019, which includes the influence of internal variability (e.g., ENSO) and anthropogenic greenhouse gases. | |

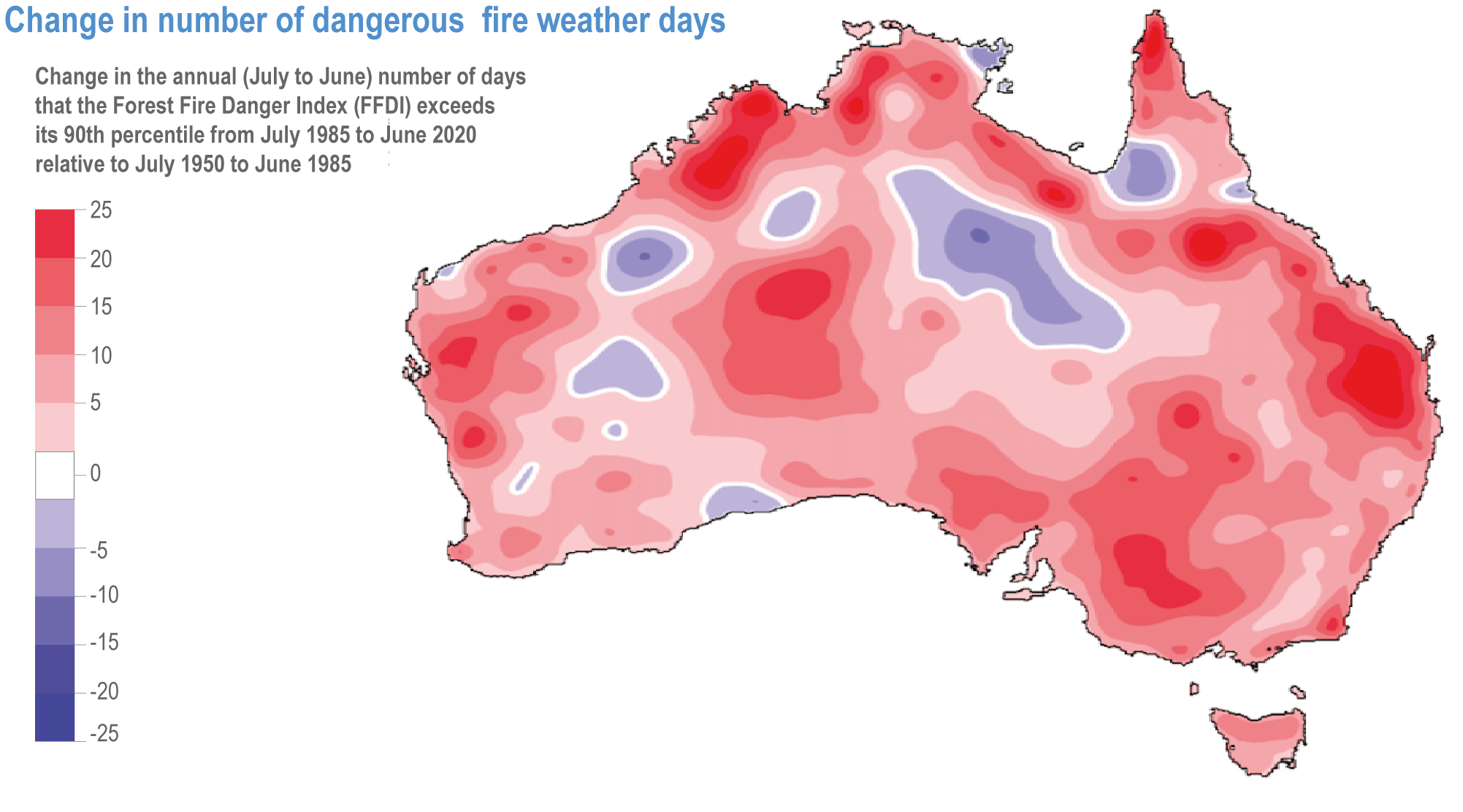

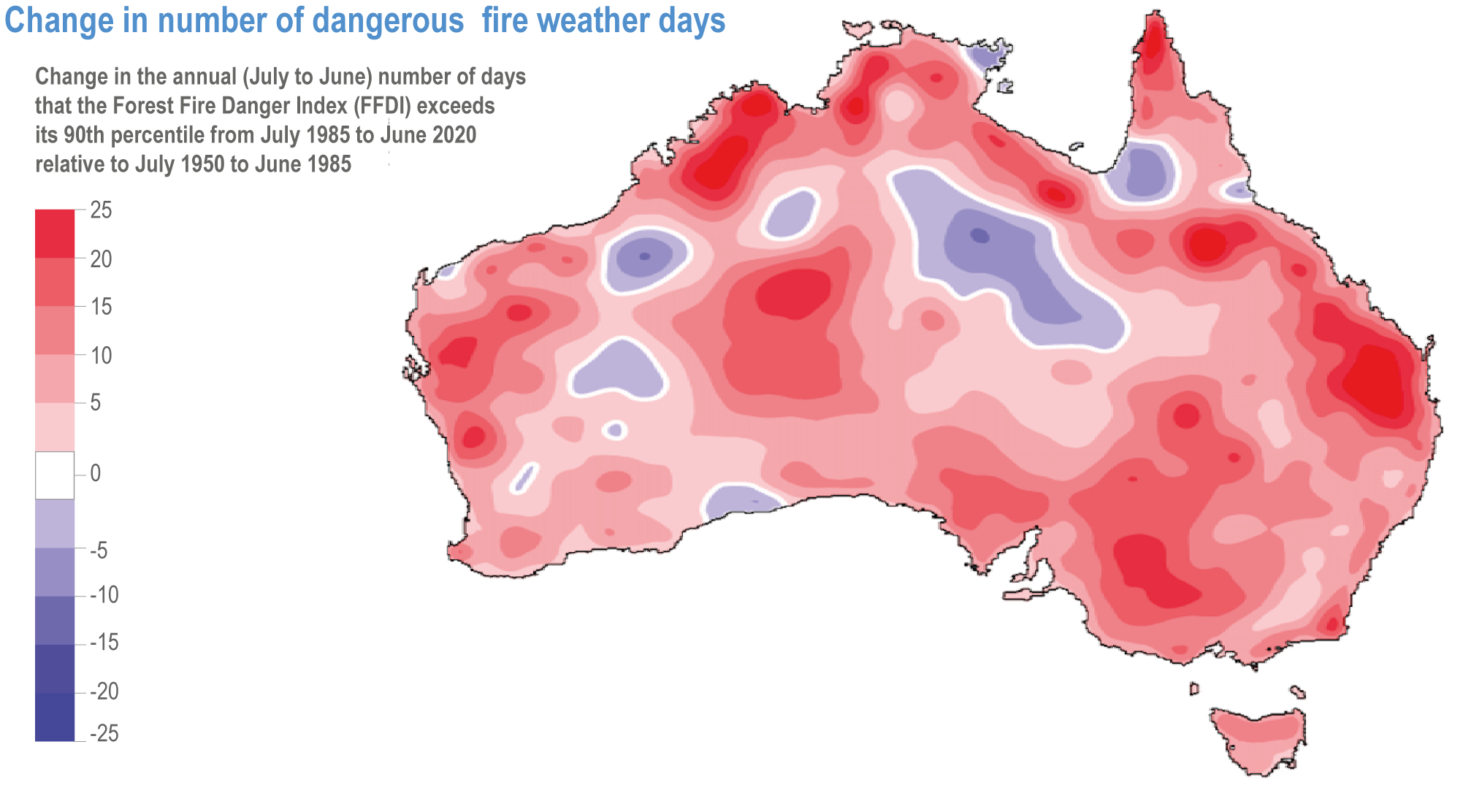

Fire | An increase in the number of extreme fire weather days from July 1950 to June 1985 compared to July 1985 to June 2020, especially in the south and east, partly attributed to climate change. More dangerous conditions for extreme pyro convection events since 1979, particularly in south-eastern Australia. Extreme fire weather in 2019–2020 was at least 30% more likely due to climate change. | (Dowdy and Pepler, 2018; BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ; van Oldenborgh et al., 2021) |

Tropical cyclones and other storms | Fewer tropical cyclones since 1982, with a 22% reduction in translation speed over Australian land areas in the period1949–2016. No significant trend in the number of East Coast Lows. From 1979 to 2016, thunderstorms and dry lightning decreased in spring and summer in northern and central Australia, decreased in the north in autumn, and increased in the southeast in all seasons. Convective rainfall intensity per thunderstorm increased by about 20% in the north and 10% in the south. An increase in the frequency of large to giant hail events across southeastern Queensland and northeastern and eastern New South Wales in the most recent decade. Seven major hail storms over eastern Australia from 2014 to 2020 and three major floods over eastern Australia from 2019 to 2021. | (Pepler et al., 2015b; Ji et al., 2018; Kossin, 2018; BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ; Dowdy, 2020; ICA, 2021; Bruyère et al., 2020) |

Snow | At Spencers Creek (1830 m elevation) in NSW, annual maximum snow depth decreased 10% and length of snow season decreased 5% during 2000–2013 relative to 1954–1999. At Rocky Valley Dam (1650 m elevation) in Victoria, annual maximum snow depth decreased 5.7 cm/decade from 1954 to 2011. At Mt Hotham, Mt Buller and Falls Creek (1638–1760 m elevation), annual maximum snow depth decreased 15%/decade from 1988 to 2013. | (Bhend et al., 2012; Fiddes et al., 2015; Pepler et al., 2015a; BoM and CSIRO, 2020 ) |

Ocean acidification | Average pH of surface waters has decreased since the 1880s by about 0.1 (over 30% increase in acidity). |

Table 11.3b | Projected climate change for New Zealand. Projections are given for different RCPs (RCP2.6 is low, RCP4.5 is medium, RCP8.5 is high) and years (e.g., 20-year period centred on 2090). Uncertainty ranges are 5th–95th percentiles, and median projections are given in square brackets where possible. Preliminary projections (10th–90th percentiles) based on CMIP6 models are included for some climate variables from the IPCC (2021) WGI report.

Climate variable | Projected change (year, RCP) relative to 1986–2005 | References |

Air temperature | Annual mean temperature

| (MfE, 2018); |

Sea surface temperature |

| |

Air temperature extremes |

| |

Rainfall | Annual mean rainfall

| |

Rainfall extremes | Intensity of daily rain with 20-year recurrence interval

| |

Drought | Increase in potential evapotranspiration deficit

| |

Wind speed | 99th percentile of daily mean wind speed

| |

Sea level rise |

These projections have not been updated to include an Antarctic dynamic ice sheet factor which increased global sea level projections for RCP 8.5 by approx. 10 cm. Preliminary CMIP6 projections indicate 40–50 cm (2090, SSP1-RCP2.6) and 70–90 cm (2090, SSP5-RCP8.5). | |

Sea level extremes | For a rise in sea level of 30 cm, the 1-in-100-year high water levels may occur about

| |

Fire |

| |

Tropical cyclones and other storms | Poleward shift of mid-latitude cyclones and potential for a small reduction in frequency | |

Snow and ice |

| (Hendrikx et al., 2013; MfE, 2018; Marzeion et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2021) |

Ocean acidification | pH is projected to drop by about 0.1 (2090, RCP2.6) to 0.3 (2090 RCP8.5). |

Table 11.4 | Observed impacts on terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and species in the region where there is documented evidence that these are directly (e.g., a species thermal tolerances are exceeded) or indirectly (e.g., through changed fire regimes) the result of climate change pressures.

Ecosystem | Climate-related pressure | Impact | Source |

Australia | |||

Forest and woodlands of southern and southwestern Australia | 30-year declining rainfall | Drought-induced canopy dieback across a range of forest and woodland types (e.g., northern jarrah) | |

Multiple wildfires in short succession resulting from increased fire risk conditions, including declining winter rainfall and increasing hot days | Local extirpations and replacement of dominant canopy tree species and replacement by woody shrubs due to seeders having insufficient time to reach reproductive age (alpine ash) or vegetative regeneration capacity is exhausted (snow gum woodlands) | (Slatyer, 2010; Bowman et al., 2014; Fairman et al., 2016; Harris et al., 2018; Zylstra, 2018) | |

Background warming and drying created soil and vegetation conditions that are conducive to fires being ignited by lightning storms in regions that have rarely experienced fire over the last few millennia | Death of fire-sensitive trees species from unprecedented fire events (Palaeo-endemic pencil pine forest growing in sphagnum, Tasmania, killed by lightning-ignited fires in 2016) | ||

Australian Alps Bioregion and Tasmanian alpine zones | Severe winter drought; warming and climate-induced biotic interactions | Shifts in dominant vegetation with a decline in grasses and other graminoids and an increase in forb and shrub cover in Bogong High Plains, Victoria, Australia | |

Snow loss, fire, drought and temperature changes | Changing interactions within and among three key alpine taxa related to food supply and vegetation habitat resources: The mountain pygmy-possum (Burramys parvus), the mountain plum pine (Podocarpus lawrencei) and the bogong moth (Agrostis infusia) | ||

Retreat of snow line | Increased species diversity in alpine zone | ||

Reduced snow cover | Loss of snow-related habitat for alpine zone endemic and obligate species | (ACE CRC, 2010; Pepler et al., 2015a; Thompson, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2019) | |

Wet Tropics World Heritage Area | Warming and increasing length of dry season | Some vertebrate species have already declined in both distribution area and population size, both earlier and more severely than originally predicted | |

Sub-Antarctic Macquarie island | Reduced summer water availability for 17 consecutive summers, and increases in mean wind speed, sunshine hours and evapotranspiration over four decades | Dieback in critically endangered habitat-forming cushion plant Azorella macquariensis in the fellfield and herb field communities | |

Mass mortality of wildlife species (flying foxes, freshwater fish) | Extreme heat events; rising water temperatures, temperature fluctuations, altered rainfall regimes including droughts and reduced in-flows | Flying foxes—thermal tolerances of species exceeded; fish—amplified extreme temperature fluctuations, increasing annual water basin temperatures, extreme droughts and reduced runoff after rainfall | |

Bramble Cay melomys (mammal) Melomys rubicola | SLR and storm surges in Torres Strait | Loss of habitat and global extinction | (Lunney et al., 2014; Gynther et al., 2016; Waller et al., 2017; CSIRO, 2018) |

Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus | Increasing drought and rising temperatures, compounding impacts of habitat loss, fire and increasing human population | Population declines and enhanced risk of local extinctions | |

Tawny dragon lizard, Ctenophorus decresii | Desiccation stress driven by higher body temperatures and declining rainfall | Population decline and potential local extinction in Flinders Ranges, south Australia | |

Birds | Changing thermal regimes including increasing thermal stress and changes in plant productivity are identified as being causal | Changes in body size, mass and condition and other traits linked to heat exchange | (Gardner et al., 2014a; Gardner et al., 2014b; Campbell-Tennant et al., 2015; Gardner et al., 2018; Hoffmann et al., 2019) |

New Zealand | |||

Forest birds | Warming | Increasing invasive predation pressure on endemic forest birds surviving in cool forest refugia, particularly larger-bodied bird species that nest in tree cavities and are poor dispersers | |

Coastal ecosystems | More severe storms and rising sea levels | Erosion of coastal habitats, including dunes and cliffs, is reducing habitat | |

Beech forest ecosystems | Increasing mean temperatures and indirectly through effects of events like ENSO | Increased beech mast seeding events that stimulate population irruptions for invasive rodents and mustelids, which then prey on native species | |

11.3.1.2 Projected Impacts

In the near term (2030–2060), climate change is projected to become an increasingly dominant stress on the region’s biodiversity, with some ecosystems experiencing irreversible changes in composition and structure and some threatened species becoming extinct (high confidence). Climate change will interact with current ecological conditions, threats and pressures, with cascading ecological impacts, including population declines, heat-related mortalities, extinctions and disruptions for many species and ecosystems (high confidence) (Table 11.5). These include inadequate allocation of environmental flows for freshwater fish (Vertessy et al., 2019), native forest logging for old-growth-forest-dependent fauna (Lindenmayer et al., 2015; Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020a; Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020b), and invasive species (Scott et al., 2018). Climate change has synergistic and compounding impacts, particularly in bioregions already experiencing ecosystem degradation, threatened endemics and collapse of keystone species, including those of value to Indigenous Peoples, and high extinction rates as a consequence of human activities (Table 11.4) (Gordon, 2009; Australia SoE, 2016; Weeks et al., 2016; Cresswell and Murphy, 2017; Hare et al., 2019; MfE, 2019; Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020a; Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020b; Bergstrom et al., 2021). Some native species are projected to have potentially greater geographic range if they can colonise new areas, while other species may be resilient to projected climate change impacts (Bulgarella et al., 2014; K.E. Lawrence et al., 2017; Conroy et al., 2019; Rizvanovic et al., 2019).

Table 11.5 | An indicative selection of projected climate-change impacts on terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and species in Australia and New Zealand respectively.

Ecosystem, species | Climate-related pressure | Projected Impact | Source |

Australia | |||

Floristic composition of vegetation communities | Increases in temperature and reductions in annual precipitation by 2070. Many plant species based on median projection from five global climate models (ACCESS1.0, CNRM-CM5, HADGEM2-CC, MIROC5, NorESM1-M) centred on the decade 2070 under RCP8.5 | 47% of vegetation types have characteristic plant species at risk of their climatic tolerances being exceeded from increasing mean annual temperature by 2070 with only 2% at risk from reductions in annual precipitation by 2070 | |

Some south east Australian temperate forests | Reduction in winter rainfall and rising spring temperatures resulting in an increase in the frequency of very high fire weather conditions and increased risk of catastrophic wildfires; based on output from 15 CMIP5 GCMs using RCP8.5 for years for 2060–2079 as compared to 1990–2009 | Increase in fire frequency prevents recruitment of obligate seeder resulting in changing dominant species and vegetation structure including long lasting or irreversible shift in formation from tall wet temperate eucalypt forests dominated by obligate seeder trees (e.g., alpine ash) to open forest or in worst case to shrubland Declining rainfall and regolith drying, more unplanned, intense fires and declining productivity place stress on tree growth and compromise biodiversity in northern jarrah forest | (Doherty et al., 2017; Zylstra, 2018; Bowman et al., 2019; Dowdy et al., 2019; Naccarella et al., 2020) |

Tree line stasis or regression (snow gum) | (Doherty et al., 2017); (Bowman et al., 2019; Naccarella et al., 2020) | ||

Increase in lightning-ignited landscape fires along with contracting palaeo-endemic refugia due to warmer and drier climates | Population collapse and severe range contraction of slow-growing, fire-sensitive palaeo-endemic temperate rainforest species (e.g., pencil pine) | ||

Rhizosphere responses or accelerated rates of soil organic matter decomposition | Plant nutrient availability may be enhanced | ||

Alpine ecosystems | Increasing global warming and rising temperatures, ongoing reduction in snow cover and winter rain and increasing frequency and magnitude of wildfires | Loss of alpine vegetation communities (snow patch feldmark and short alpine herb fields) and increased stress on snow-dependent plant and animal species; changing suitability for invasive species | (Slatyer, 2010; Morrison and Pickering, 2013; Pepler et al., 2015a; Williams et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2017) |

Northern tropical savannahs | Rainfall and CO2 effects | Potentially resulting in an increase in ecosystem carbon storage | |

Murray-Darling River Basin | Drought | Reduced river flow; mass fish kills | |

Unimpaired river basins | Elevated CO2 levels | Increase plant water use reduces stream flow | |

Bearded dragons (lizards), Pogona spp. | Changes in precipitation | P. henrylawsoni and P. microlepidota to gain suitable habitat, P. nullarbor and P. vitticeps showing the most potential loss | |

Xeric bees | Broad temperate tolerances, arid climate adapted | Climate-resilient, only small response | |

Great desert skink Liopholis kintorei | Buffering capacity of underground microclimates, for nocturnal and crepuscular ectotherms | Warming impacts projected to be indirect | |

22 narrow-range fish species in imminent risk of extinction | Projected changes in rainfall, run-off, air temperatures and the frequency of extreme events (drought, fire, flood) compound risk from other key threats especially invasive species | Extinction projected within next 20 years | |

Freshwater taxa (freshwater fish, crayfish, turtles and frogs) | Changed hydrological regimes | Substantial changes to the composition of faunal assemblages in Australian rivers well before the end of this century, with gains/losses balanced for fish but suitable habitat area predicted to decrease for many crayfish and turtle species and nearly all frog species | |

New Zealand | |||

Modified lowland wetlands | Intersection of warming, drought and heavy rainfall (ex-tropical cyclones) | Prolonged anoxic conditions in waterways (blackwater events) leading to mortality of fish (e.g., shortfin eels) and invertebrates, while botulism outbreaks can lead to impacts on waterfowl | |

Native forests and lands | Elevated CO2 levels, warming, increased precipitation. | Short-term beneficial effects on carbon storage; droughts in eastern areas would decrease productivity and rates of carbon storage in the medium term | |

Increased fire intensity and frequency in hot and dry parts of New Zealand | Much of the native vegetation has no fire adaptations, causing vulnerability to local extinction due to ‘interval squeeze’ | ||

Freshwater rivers | Rainfall variation | Cascading effects of warming, drought, floods and algal blooms compounded by water abstraction | |

Three species of naturalised woody weeds | Warming and increased CO2 levels | Increased geographic range | |

Kauri tree, Agathis australis | Lower than average rainfall stimulates a drought-deciduous response in this evergreen species | Increased litter fall | |

Windmill palm | Warming | Increased geographic range | |

New Zealand tussock grasslands | Warming | Enhanced respiration | |

Invasive species | Warming | Increased invasive species abundance and increased predation on native species | |

Warming | Expanded ranges of invasive species in higher/cooler areas | ||

Warming | Change in flowering phenology and pollination competition | ||

Warming | Increase in invasive plants, insects and pathogens from sub-tropical/tropical climates | ||

Tuatara (reptile), Sphenodon punctatus | Warming | Temperature-dependent sex determination with more male hatches threatening small, isolated populations | |

Warming | Increased geographic range | ||

Cattle tick | Warming | Increased geographic range and risk of tick-spread anaemia in cattle | (K.E. Lawrence et al., 2017) |

Brown mudfish, Neochanna apoda | Drought | Reduced flow regimes associated with drought interact with reduced habitat due to land use change, leading to population declines and potential local extinction | |

Suter’s skink (lizard)Oligosoma suteri | Warming | Increased suitable range but unclear if dispersal is possible because habitats are isolated | |

Threatened endemic passerine bird, Notiomystis cincta | Fluctuations in total precipitation, particularly increased and more variable rainfall | Heavy rainfall can flood nests and kill fledglings while droughts can cause population-wide reproductive failure | |

Feral cats | Warming | Increased geographic range |

In southern Australia, some forest ecosystems (alpine ash, snow gum woodland, pencil pine, northern jarrah) are projected to transition to a new state or collapse due to hotter and drier conditions with more fires (high confidence) (Table 11.5). In Australia, most native eucalyptus forest plants have a range of traits that enable them to persist with recurrent fire through recovery buds (sprouters) or regenerate through seeding (Collins, 2020), affording them a high level of resilience. For high-end projected 2060–2080 fire weather conditions in southeast Australia (Clarke and Evans, 2019), stand-killing wildfires could occur at a severity and frequency greater than the regenerative capacity of seeders (Enright et al., 2015; Clarke and Evans, 2019). Most New Zealand native plants are not fire resistant and are projected to be replaced by fire-resistant introduced species following climate-change-related fires (Perry et al., 2014).

A loss of alpine biodiversity in the southeast Australian Alps bioregion is projected in the near-term as a result of less snow on snow patch feldmark and short alpine herb fields as well as increased stress on snow-dependent plant and animal species (high confidence) (Table 11.3, Table 11.5). In Australia, invasive plants’ and weeds’ response rates are expected to be faster than for native species, and climate change could foster the appearance of a new set of weed species, with many bioregions facing increased impacts from non-native plants (medium confidence) (Gallagher et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2014; March-Salas and Pertierra, 2020) (Table 11.5), along with declines in some listed weeds (Duursma et al., 2013; Gallagher et al., 2013). In New Zealand, climate change is projected to enable invasive species to expand to higher elevations and southwards (medium confidence) (Table 11.5) (Giejsztowt et al., 2020; MfE, 2020a).

Projected responses of ecosystem processes are uncertain in part due to complex interactions of climate change with soil respiration, plant nutrient availability (Hasegawa et al., 2015; Orwin et al., 2015; Ochoa-Hueso et al., 2017) and changing fire regimes (Table 11.5) (Scheiter et al., 2015; Dowdy et al., 2019). For aquatic biota, responses will reflect seasonal differences in water temperature (Wallace et al., 2015) and changes in rainfall intensity, productivity and biodiversity (Jardine et al., 2015). Extreme floods may have negative impacts on New Zealand river biota, by mobilising nutrients, sediments and toxic chemicals and aiding the dispersal of invasive species. These effects are compounded by homogenisation of rivers through channelisation (Death et al., 2015).

Improved coastal modelling, experiments and in situ studies are reducing uncertainties at a local scale about the impact of future sea level rise (SLR) on coastal freshwater terrestrial wetlands (medium confidence) (Shoo et al., 2014; Bayliss et al., 2018; Grieger et al., 2019). Low-lying coastal wetlands are susceptible to saltwater intrusion from sea level rise (SLR) (Shoo et al., 2014; Kettles and Bell, 2015; Finlayson et al., 2017) with consequences for species dependent on freshwater habitats (Houston et al., 2020). Saline habitat conditions will move inland and new coastal ecosystem states may emerge, including the World Heritage listed Kakadu’s freshwater wetland (Bayliss et al., 2018) (Table 11.5). Increasingly, sea level rise (SLR) will shrink the intertidal zone, having implications for wading birds which use this zone (Tait and Pearce, 2019) (Box 11.6). The ecology of freshwater wetlands in New Zealand are projected to be impacted by the intersection of warming, drought and heavy rainfall (Pingram et al., 2021) (Table 11.5).

The impacts on species from projected global warming depend on their physiological and ecological responses for which knowledge is limited (Table 11.5) (Bulgarella et al., 2014; Carter et al., 2018; Green et al., 2021). Knowledge of projected impacts is constrained by uncertainties about the influence of physiological limits, barriers to dispersal, competition, the availability of habitat resources (Worth et al., 2014) and disruptions to ecological interactions (Lakeman-Fraser and Ewers, 2013; Parida et al., 2015; Porfirio et al., 2016). Gaps in ecological modelling of future climate impacts include consideration of long-term rainfall and temperature changes (Grimm-Seyfarth et al., 2017; Grimm-Seyfarth et al., 2018), species dispersal rates, evolutionary capacity and phenotypic plasticity and the thresholds at which they are considered adequate to counter the impacts of climate change (Ofori et al., 2017b), as well as indirect effects including sea level rise (SLR) and altered fire regimes (Shoo et al., 2014; Cadenhead et al., 2016; He et al., 2016).

11.3.1.3 Adaptation

Managing climate change risks to ecosystems is primarily based on reducing the impact of other anthropogenic pressures, including invasive species, and facilitating natural adaptation (high confidence). This approach is most feasible within protected areas on public, private and Indigenous land and sea (Bellard et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2020) but is also applicable elsewhere (Barnes et al., 2015). Effective strategies promote ecosystem resilience by changing unsustainable land uses and management practices, increasing habitat connectivity, controlling introduced species, restoring habitats, implementing appropriate fire management, integrated risk assessment and adaptation planning (B. Frame et al., 2018; Lindenmayer et al., 2020; Macinnis-Ng et al., 2021). Complementary approaches include ex situ seed banks (Morrison and Pickering, 2013; Christie et al., 2020).

Best practice conservation adaptation planning is informed by data on key habitats, including refugia, and restoration that facilitates species movements and employs adaptive pathways (very high confidence) (Guerin and Lowe, 2013; Reside et al., 2014; Shoo et al., 2014; Keppel et al., 2015; Andrew and Warrener, 2017; Baumgartner et al., 2018; Harris et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2018a; Das et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2019; Molloy et al., 2020). Landscape planning (Bond et al., 2014; McCormack, 2018) helps reduce habitat loss, facilitates species dispersal and gene flow (McLean et al., 2014; Shoo et al., 2014; Lowe et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2018; McCormack, 2018) and allows for new ecological opportunities (Norman and Christidis, 2016). Coastal squeeze is a threat to freshwater wetlands and requires planning for the potential inland shift (Grieger et al., 2019). Adaptations that maintain critical volumes and periodicity of environmental flows will help protect freshwater biodiversity (Box 11.3) (Yen et al., 2013; Barnett et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018b).

Adaptation planning for ecosystems and species requires monitoring and evaluation to identify trigger points and thresholds for new actions to be implemented (high confidence) (Tanner-McAllister et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2020). Best planning practice includes keeping options open (Barnett et al., 2015; Dunlop et al., 2016; Finlayson et al., 2017) and updating management plans in light of new information. New insights are emerging into how species’ natural adaptive capacities can inform adaptation planning (Llewelyn et al., 2016; Steane et al., 2017; Hoeppner and Hughes, 2019). Physiological limits to adaptation in some species are being identified (Barnett et al., 2015; Sorensen et al., 2016), and where natural responses are not feasible, human-assisted translocations may be warranted (Becker et al., 2013; Chauvenet et al., 2013; Innes et al., 2019) for some species (Ofori et al., 2017a; Ofori et al., 2017b). Legal reform may be needed to better enable climate adaptation for biodiversity conservation that recognises species’ natural adjustments to their distributions and the difficulties encountered in predicting the consequences for ecological interactions and ecosystem services (McCormack, 2018; McDonald et al., 2019).

Adaptation research priorities include understanding of the interactions and cumulative impacts of existing stressors and climate change and the implications for managing ecosystems and natural resources (Williams et al., 2020). For Australia, research on implementation strategies for conservation and managing threats, stress and natural assets is a priority (Williams et al., 2020). For New Zealand, understanding how terrestrial ecosystems and species respond to climate change is a priority, and where existing stressors are affecting freshwater quantity and quality, in situ monitoring to detect and evaluate projections of climate change impacts on biodiversity and a national data repository are lacking (MfE, 2020a). The projected increase in invasive species indicates the importance of a step-up in pest management efforts to ensure native species persistence as invasive species spread from climate change (Firn et al., 2015). There remains a gap between the knowledge generated, potential adaptation strategies and their incorporation into conservation instruments (medium confidence) (Graham et al., 2019; Hoeppner and Hughes, 2019), though there is increasing recognition of the need to improve governance and management structures for their implementation (Christie et al., 2020).

Box 11.1 | Escalating Impacts and Risks of Wildfire

Fire activity depends on weather, ignition sources, land management practices and fuel flammability, availability and continuity (Bradstock et al., 2014). Increased fire activity in southeast Australia associated with climate change has been observed since 1950 (Abram et al., 2021), though trends vary regionally (medium confidence) (Bradstock et al., 2014). In New Zealand, there has been an increased frequency of major wildfires in plantations (FENZ, 2018) and at the rural–urban interface (medium confidence) (Pearce, 2018). In northern Australia, increased wet season rainfall (Gallego et al., 2017) has increased dry season fuel loads (Harris et al., 2008).

In Australia, the frequency and severity of dangerous fire weather conditions is increasing, with partial attribution to climate change (very high confidence) (Dowdy and Pepler, 2018; Abram et al., 2021) (11.2.1, Figure Box 11.1.1), especially in southern and eastern Australia during spring and summer (Harris and Lucas, 2019). Although Australia’s eucalyptus forests and woodlands are fire adapted (Collins, 2020), increasing intensity and frequency of fires may exceed their resilience because of the shorter intervals between high-severity fires (Bowman et al., 2014; Etchells et al., 2020; Lindenmayer and Taylor, 2020a). Recent fires have severely impacted eastern rainforests, including significant Gondwana refugia (Abram et al., 2021). In New Zealand, the trends in very high and extreme fire weather (1997–2019) have not yet been attributed to climate change (MfE, 2020a).

Figure Box 11.1.1 | Change in the annual (July to June) number of days that the Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) exceeds its 90thpercentile from July 1985 to June 2020 relative to July 1950 to June 1985 (BoM and CSIRO, 2020; Abram et al. , 2021).

Fire weather is projected to increase in frequency, severity and duration for southern and eastern Australia (high confidence) and most of New Zealand (medium confidence) (11.2.2), with projected increases in pyro-convection risk for parts of southern Australia (Dowdy et al., 2019) and increased dry-lightning and fire ignition for southeast Australia (Mariani et al., 2019; Dowdy, 2020). Increased fire risk in spring may reduce opportunities for prescribed fuel-reduction burning in some regions (Harris and Lucas, 2019; Di Virgilio et al., 2020). Fuel dryness is a key constraint on wildfire occurrence (Ruthrof et al., 2016). Vegetation change will affect fuel load and fire risk in different areas in complex ways (Watt et al., 2019; Alexandra and Max Finlayson, 2020; Clarke et al., 2020; Sanderson and Fisher, 2020).

Direct effects of wildfire include death and injury to people and animals and damage to ecosystems, property, agriculture, water supplies and other infrastructure (Brodison, 2013; Pearce, 2018; de Jesus et al., 2020; Johnston et al., 2020; Maybery et al., 2020). Indirect effects include electricity and communication blackouts leading to cascading impacts on services, infrastructure and communities (Bowman, 2012; Schavemaker and van der Sluis, 2017).

For New Zealand, there has been recent increased frequency and magnitude of property losses due to wildfire (Pearce, 2018). The 1660-hectare Port Hills fire in 2017 resulted in the greatest house losses (9) in almost 100 years (Langer et al., 2018), but the subsequent 5540-hectare Lake Ohau fire destroyed 53 houses in 2020 (Waitaki District Council, 2020).

In Australia, between 1987 and 2016, there were 218 deaths, 1000 injuries, 2600 people left homeless and 69,000 people affected by wildfire (Deloitte, 2017b). Wildfires cost about AUD$1.1 billion per year on average (11.5.2).

The Australian wildfires of 2019–2020 resulted in 33 deaths, over 3000 houses destroyed, AUD$2.3 billion in insured losses and AUD$3.6 billion in losses for tourism, hospitality, agriculture and forestry (CoA, 2020e; Filkov et al., 2020) (Figure Box 11.1.2). Smoke caused a further 429 deaths and 3230 hospitalisations as a result of respiratory distress and illness, with health costs totalling AUD$1.95 billion (Johnston et al., 2020). These fires burnt about 5.8 to 8.1 million hectares of forest in eastern Australia (Ward et al., 2020; Godfree et al., 2021), resulting in the loss or displacement of nearly 3 billion vertebrate animals (CoA, 2020e; Wintle et al., 2020). Further, 114 listed threatened species lost at least 50% of their habitat, and 49 lost 80% (Wintle et al., 2020), among other severe ecological impacts (Hyman et al., 2020). Smoke carried over 4000 km to New Zealand, where it increased snow/glacier melt through darkening surfaces and produced a detectable odour (Pu et al. 2021;(Filkov et al., 2020). The fire season of 2019–2020 was at least 30% more likely than a century ago due to the influence of climate change (van Oldenborgh et al., 2021). Following the fires, a Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements made 80 recommendations, most of which were accepted by government, including establishing a disaster advisory body and a resilience and recovery agency (11.5.2.3) (CoA, 2020e).

In the face of climate change and the increased cost of fire damage and suppression, there has been considerable investment in fire risk reduction (Table Box 11.1.1). Recent analysis of 8800 fires in Australia shows resource constraints in response capacity are a barrier to effectively containing fires (Collins et al., 2018b), compounded by lengthened and more extreme fire seasons.

Table Box 11.1.1 | Examples of adaptation options and enablers to reduce wildfire risk (Hart and Langer, 2011; Mitchell, 2013; Price et al. , 2015; Tolhurst and McCarthy, 2016; Deloitte, 2017b; Miller et al., 2017; Steffen et al., 2017; Kornakova and Glavovic, 2018; Newton et al., 2018; Pearce, 2018; CoA, 2020e; McKemey et al., 2020).

Land management | Communications | Infrastructure |

Prescribed burning to reduce fuel load close to built assets. | Clearer communication of existing exposure and vulnerability to enable informed decisions about risk tolerance and management, including sites of key biodiversity that are sensitive or susceptible to fire. | Enhanced training and support for firefighters and aerial firefighting assets, including sharing of resources nationally and internationally to address the increasing overlap of fire seasons, which are lengthening across the world. |

Engagement with Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples to utilise and learn from their fire management knowledge and skills to assist in landscape management and greenhouse gas mitigation. | Increased research to understand interactions between fire, fuel, weather, climate and human factors to enhance projections of fire occurrence and behaviour. | Nationally consistent response to exceedance of air quality standards. |