Chapter 12: Climate Change Information for Regional Impact and for Risk Assessment

Executive Summary

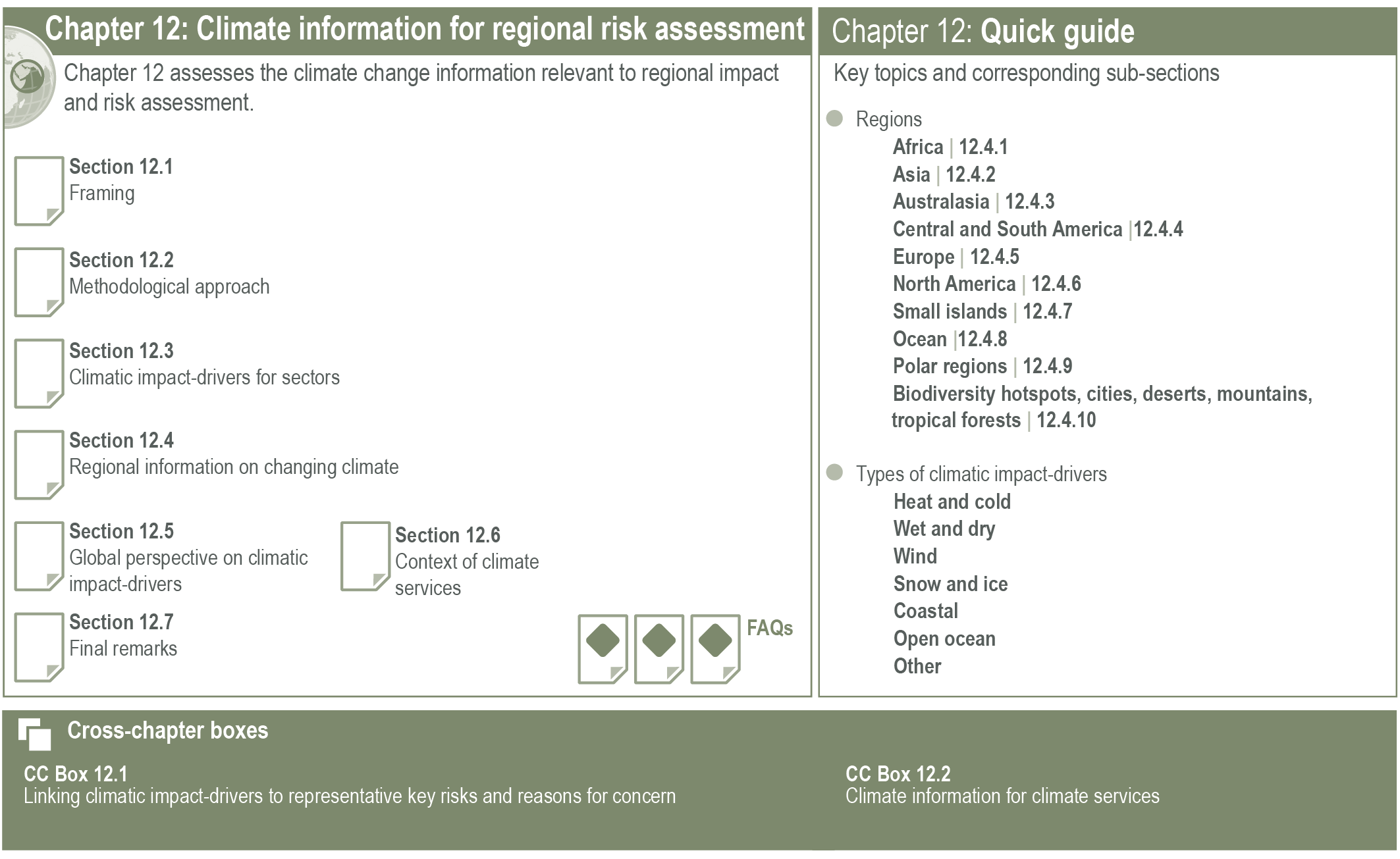

Climate change information is increasingly available and robust at regional scale for impacts and risk assessment. Climate services and vulnerability, impacts and adaptation studies require regional scale multi-decadal climate observations and projections. Since the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), the increased availability of coordinated ensemble regional climate model projections and improvements in the level of sophistication and resolution of global and regional climate models, completed by attribution and sectoral vulnerability studies, have enabled the investigation of past and future evolution of a range of climatic quantities that are relevant to socio-economic sectors and natural systems. Chapter 12 consolidates core physical knowledge from preceding AR6 Working Group I (WGI) chapters and post-AR5 climate impact assessment literature to assess the spatio-temporal evolution of the climatic conditions that may lead to regional scale impacts and risks (following the sectoral classes adopted by AR6 WGII) in the world’s regions (presented in Chapter 1). {12.1}

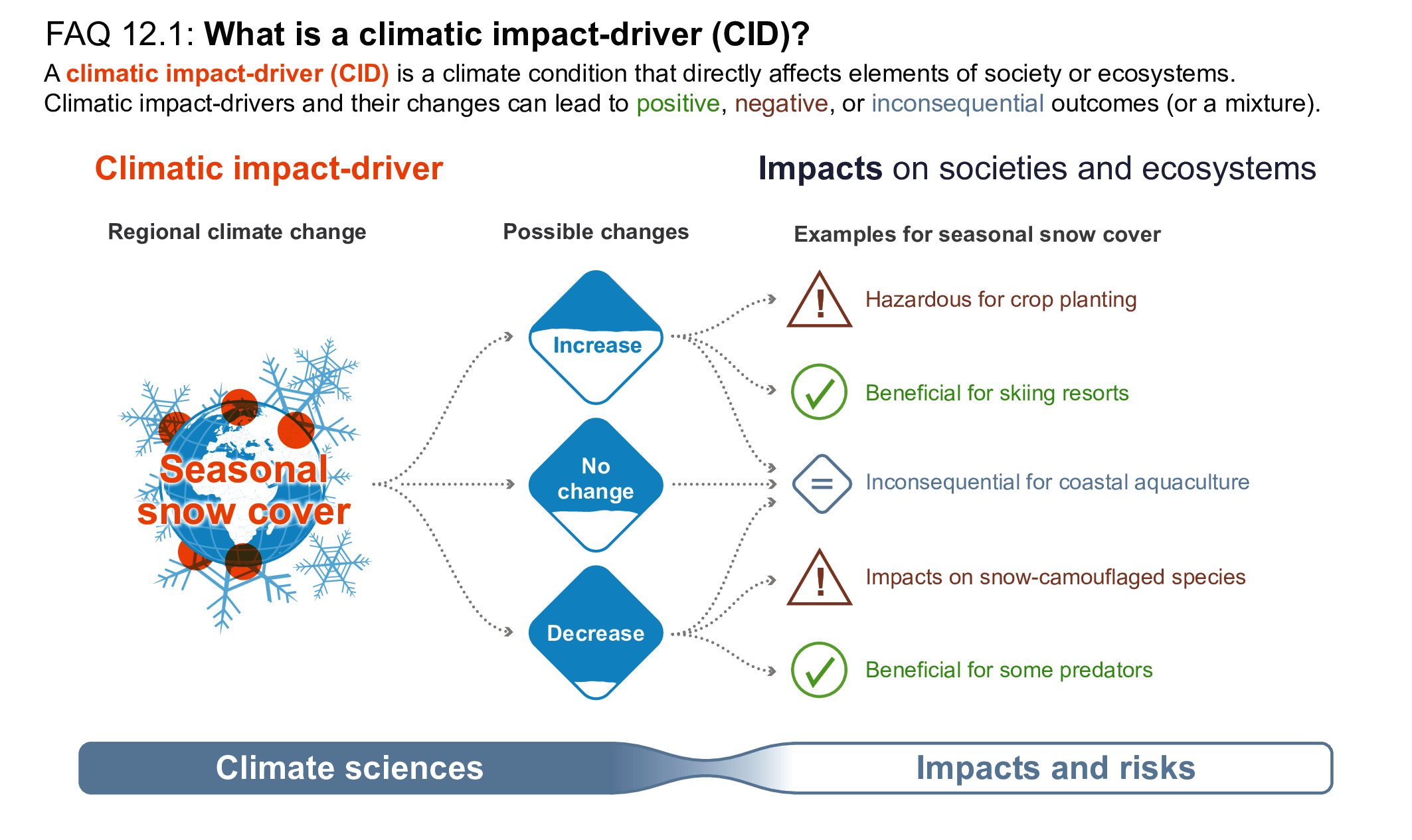

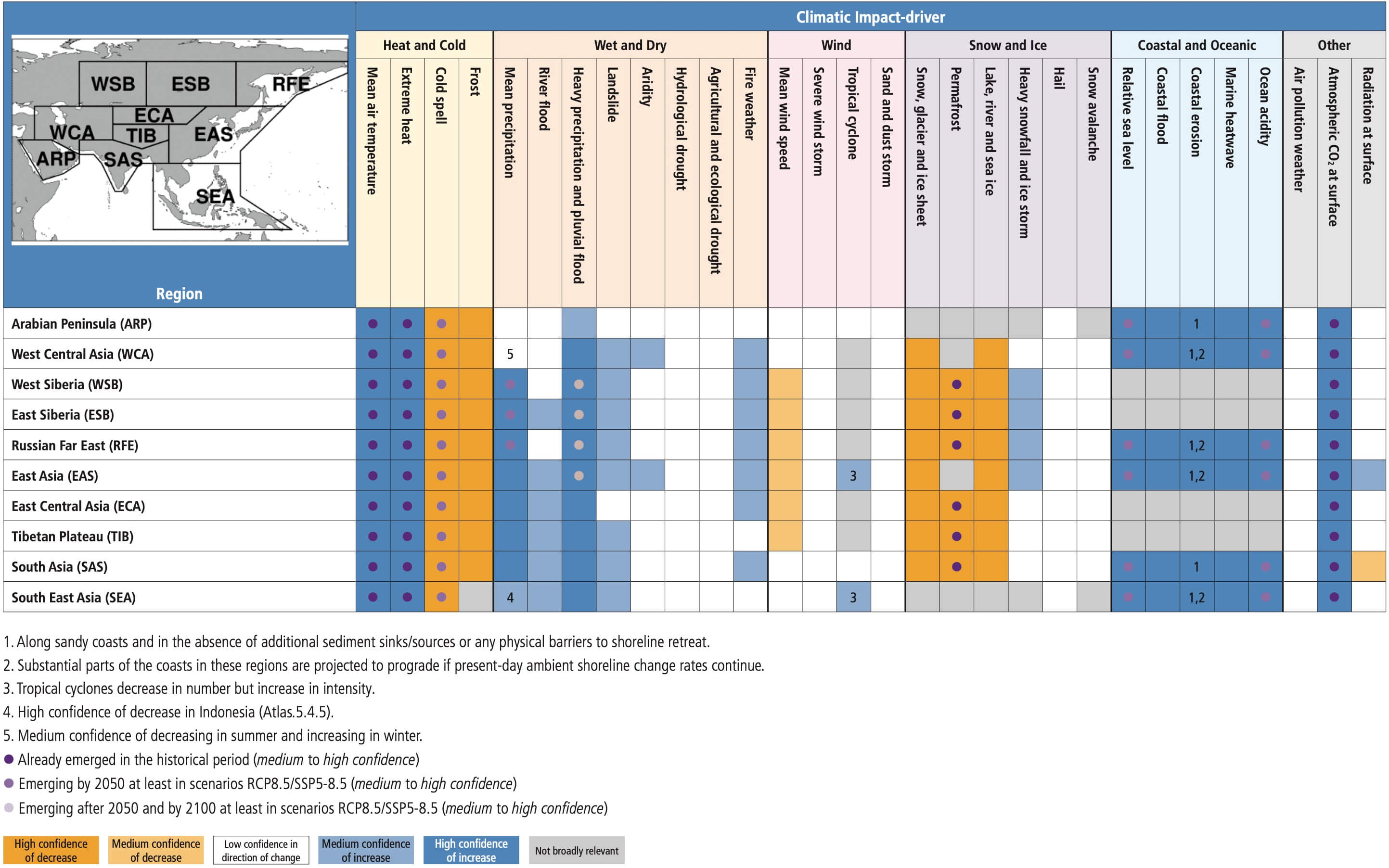

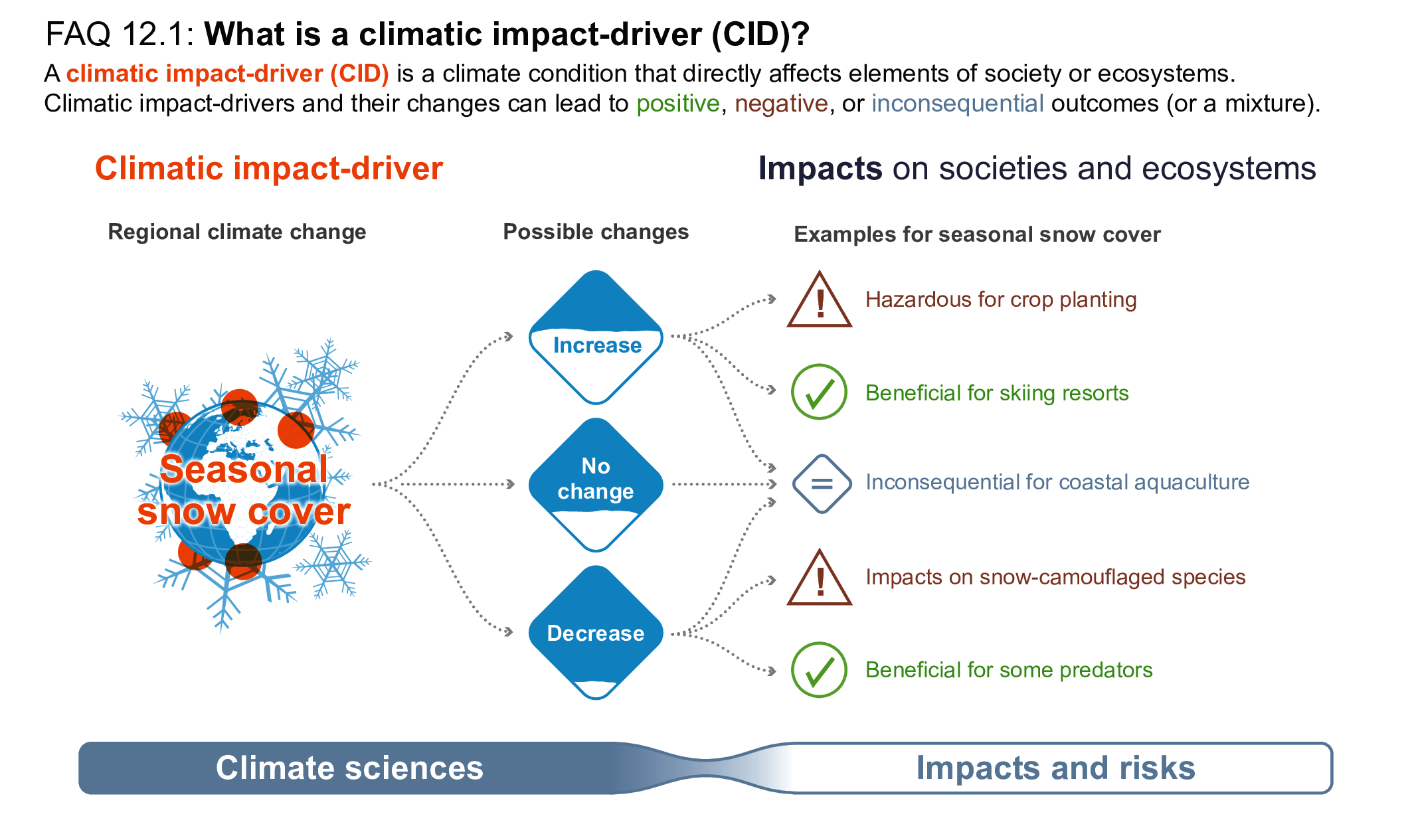

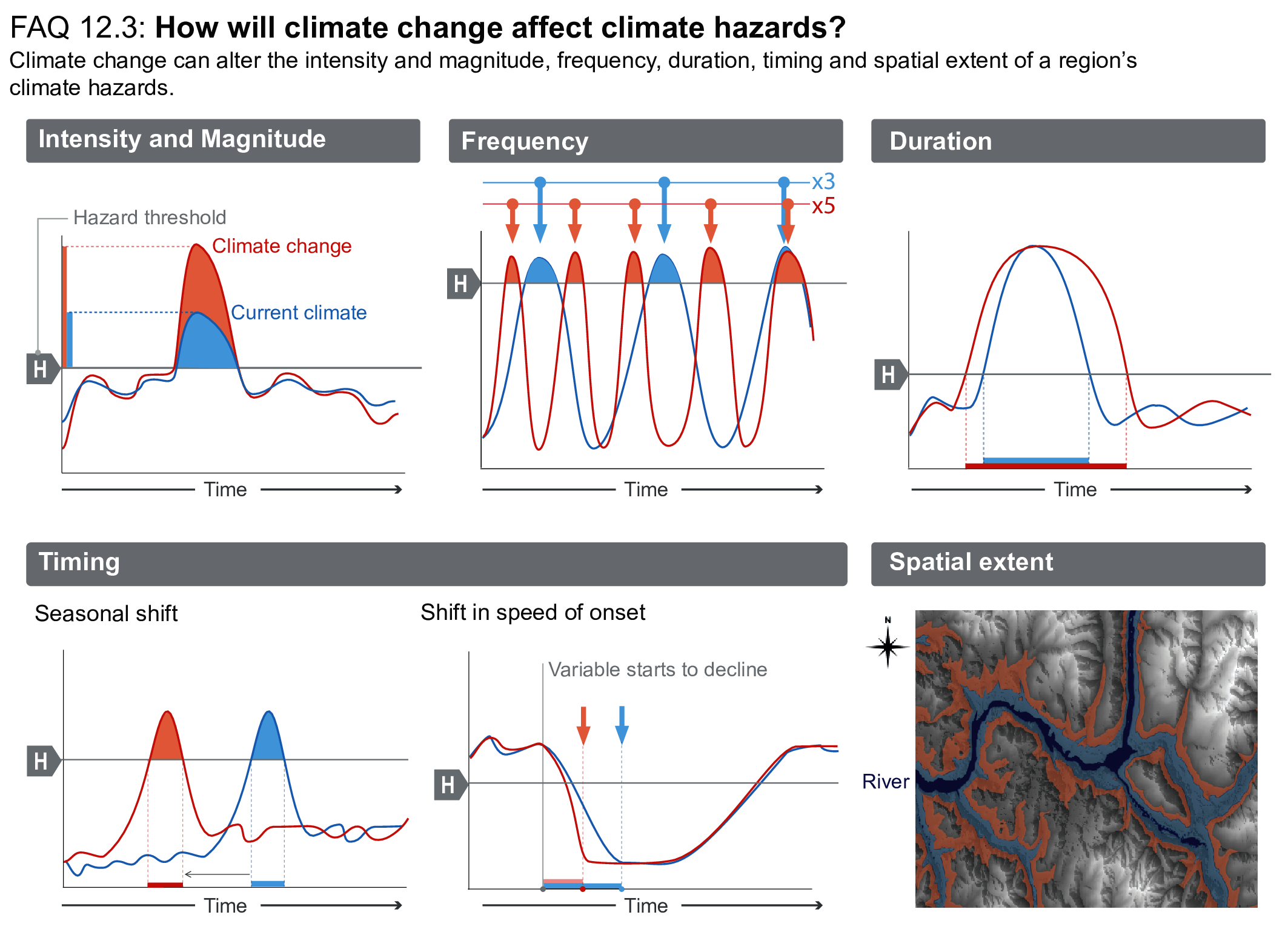

The climatic impact-driver (CID) framework adopted in Chapter 12 allows for assessment of changing climate conditions that are relevant for regional impacts and risk assessment. CIDs are physical climate system conditions (e.g., means, events, extremes) that affect an element of society or ecosystems and are thus a priority for climate information provision. Depending on system tolerance, CIDs and their changes can be detrimental, beneficial, neutral or a mixture of each across interacting system elements, regions and society sectors. Each sector is affected by multiple CIDs and each CID affects multiple sectors. A CID can be measured by indices to represent related tolerance thresholds. {12.1–12.3}

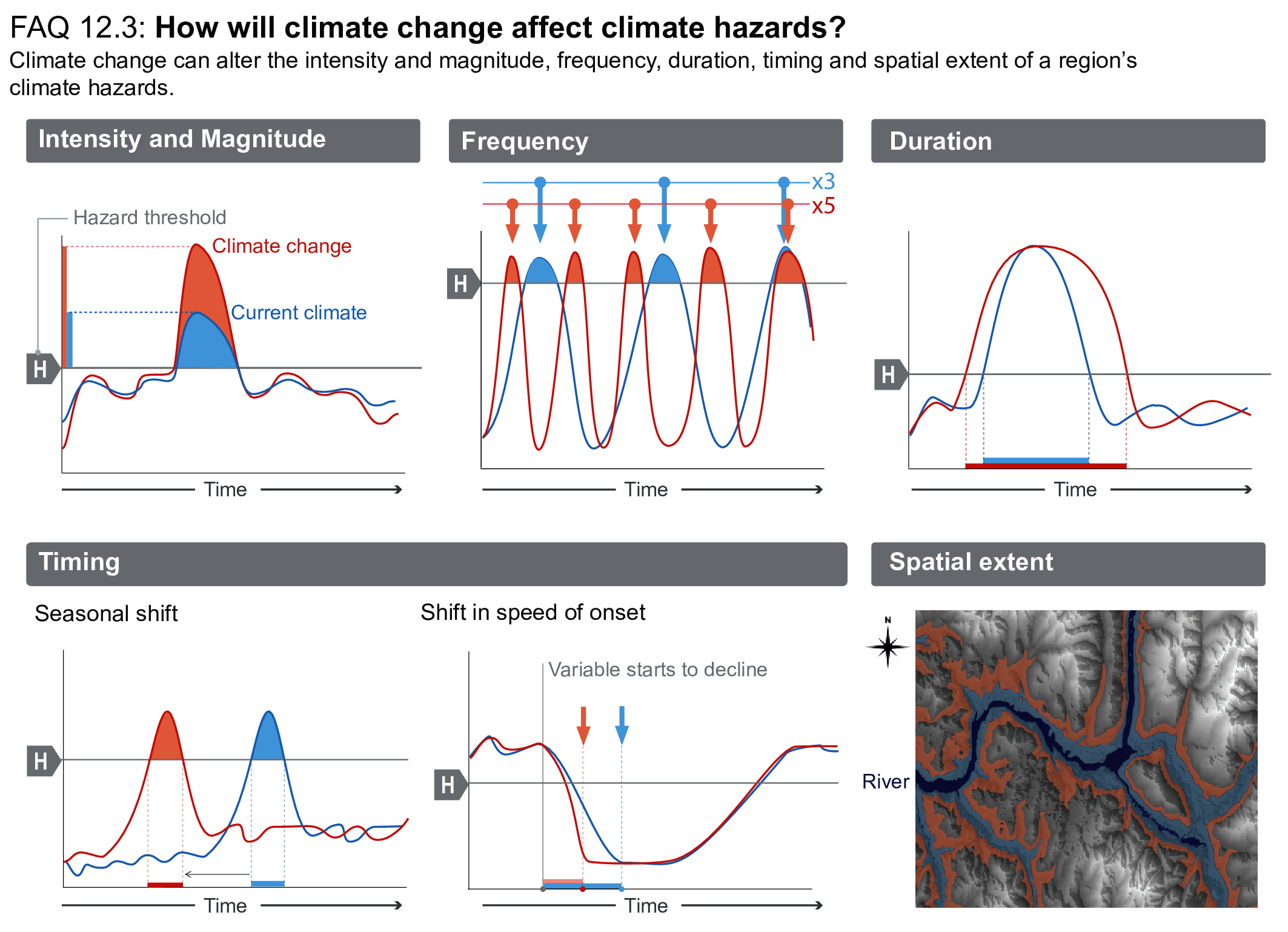

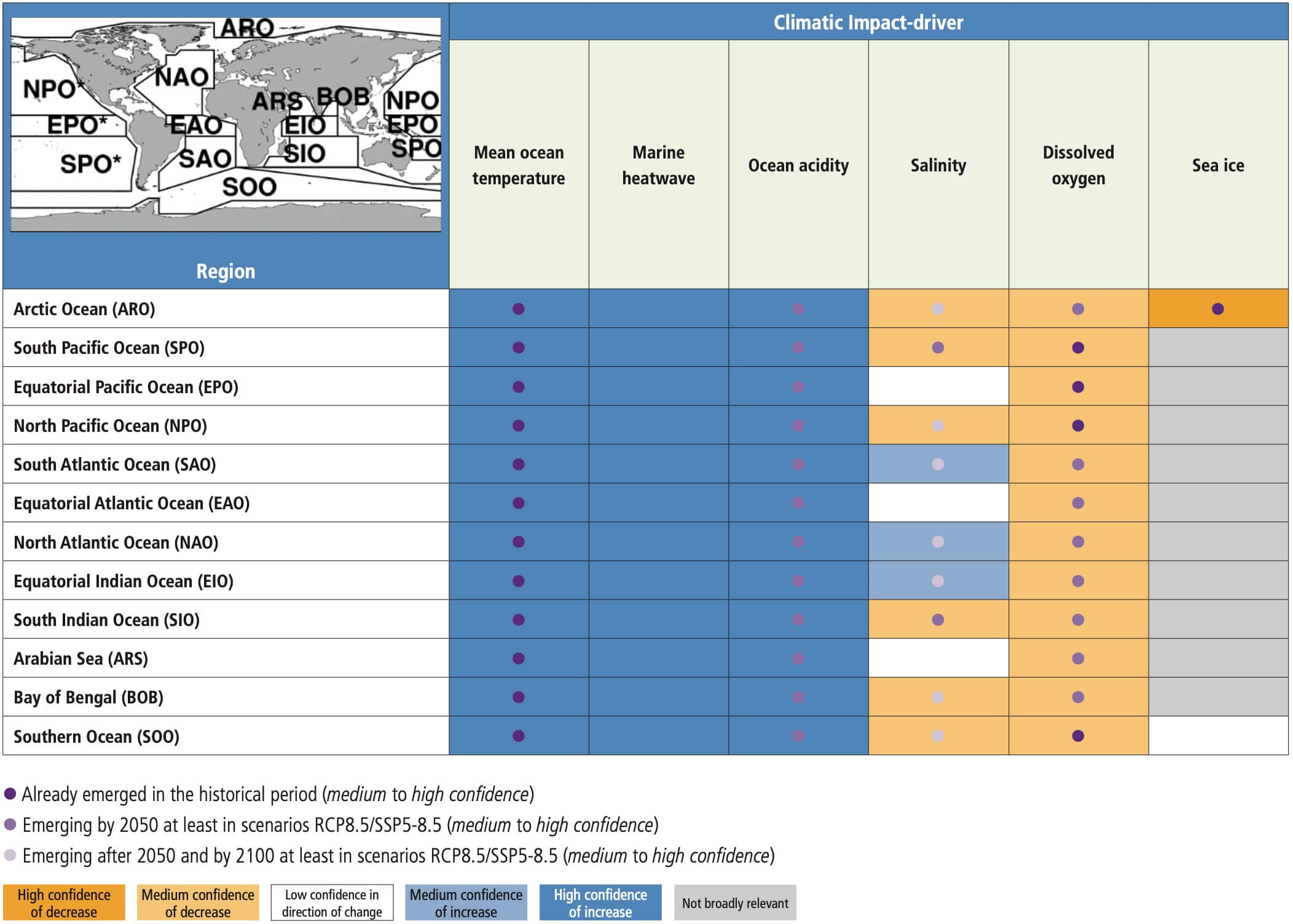

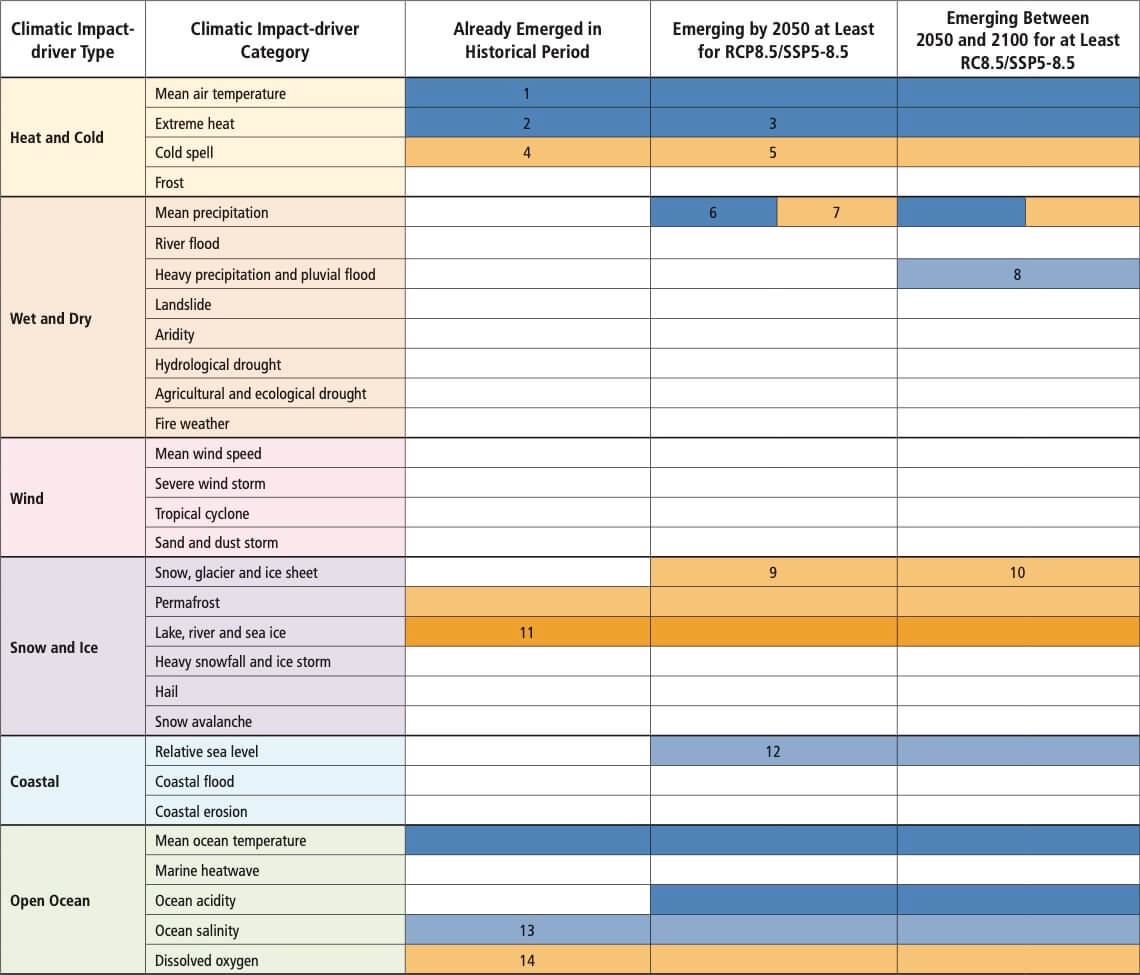

The current climate in most regions is already different from the climate of the early or mid-20th century with respect to several CIDs. Climate change has already altered CID profiles and resulted in shifts in the magnitude, frequency, duration, seasonality and spatial extent of associated indices (high confidence). Changes in temperature-related CIDs such as mean temperatures, growing season length, extreme heat and frost have already occurred and many of these changes have been attributed to human activities (medium confidence). Mean temperatures and heat extremes have emerged above natural variability in all land regions (high confidence). In tropical regions, recent past temperature distributions have already shifted to a range different to that of the early 20th century (high confidence). Ocean acidification and deoxygenation have already emerged over most of the global open ocean, as has reduction in Arctic sea ice (high confidence). Using CID index distributions and event probabilities accurately in both current and future risk assessments requires accounting for the climate change-induced shifts in distributions that have already occurred. {12.4, 12.5}

Several impact-relevant changes have not yet emerged from the natural variability but will emerge sooner or later in this century depending on the emissions scenario (high confidence). Increasing precipitation is projected to emerge before the middle of the century in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (high confidence). Decreasing precipitation will emerge in a very few regions (Mediterranean, Southern Africa, south-western Australia) (medium confidence) by mid-century (medium confidence). The anthropogenic forced signal in near-coast relative sea level rise will emerge by mid-century RCP8.5 in all regions with coasts, except in the West Antarctic region where emergence is projected to occur before 2100 (medium confidence). The signal of ocean acidification in the surface ocean is projected to emerge before 2050 in every ocean basin (high confidence). However, there is limited evidence of drought trends emerging above natural variability in the 21st century. {12.5}

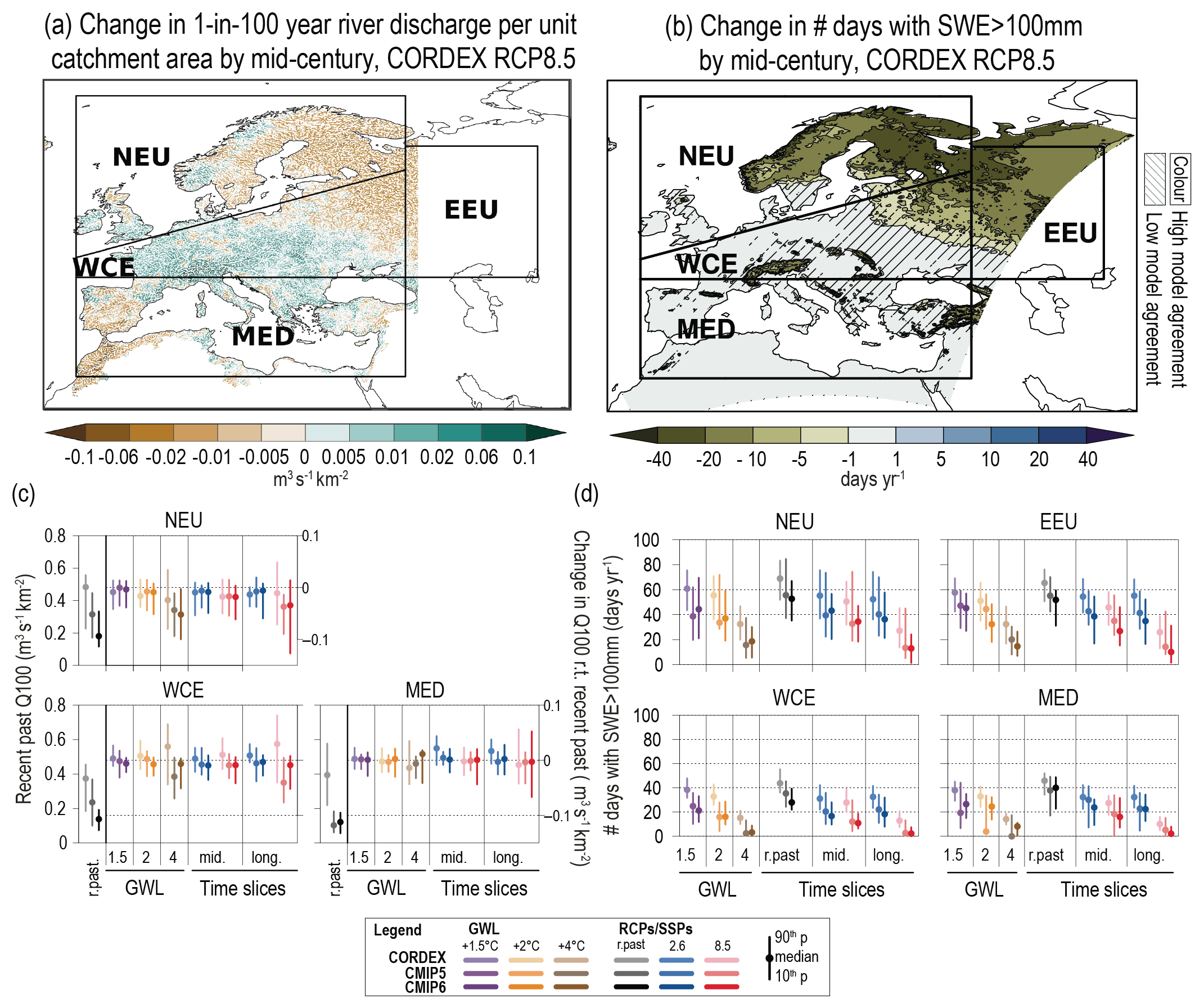

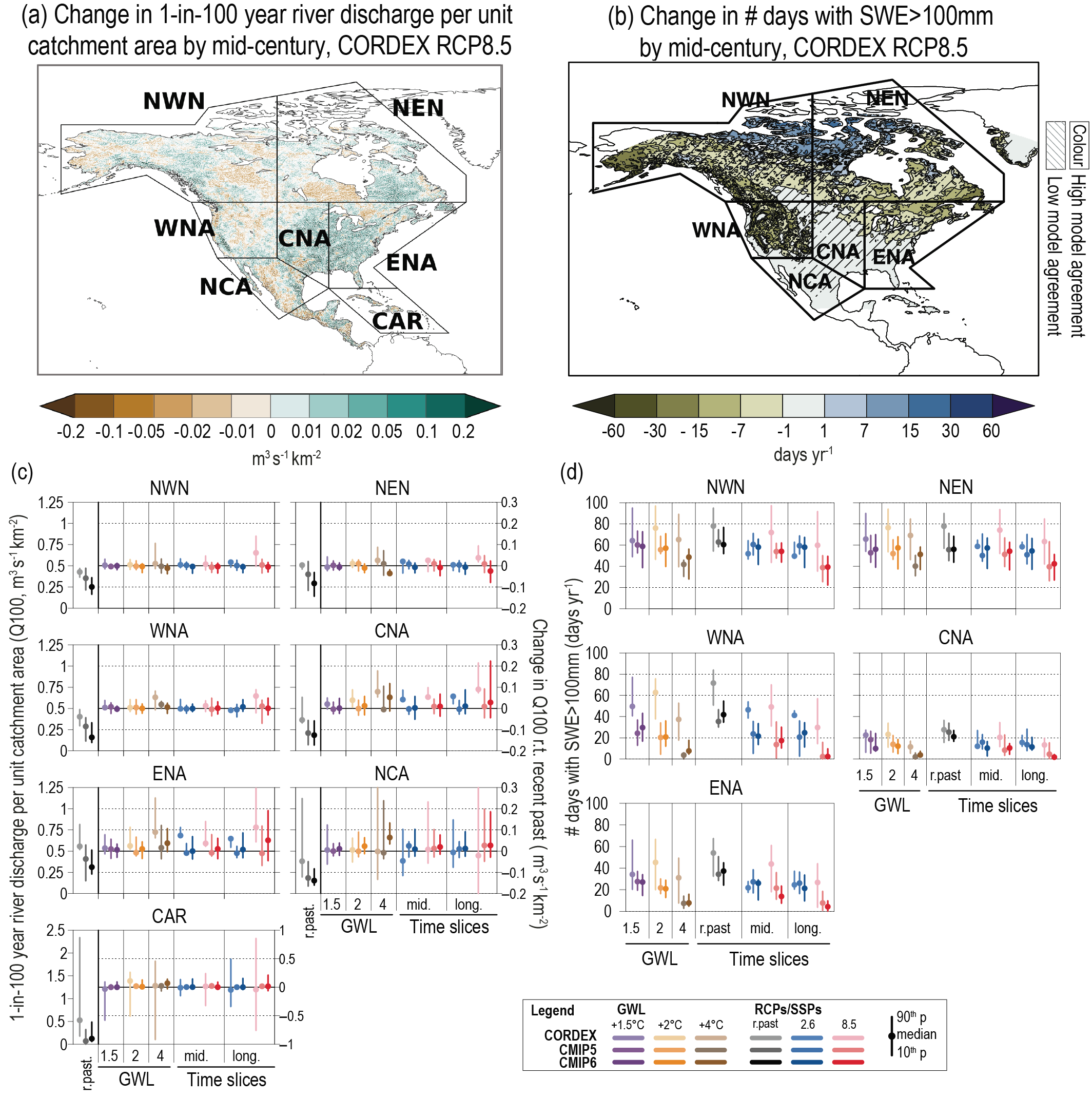

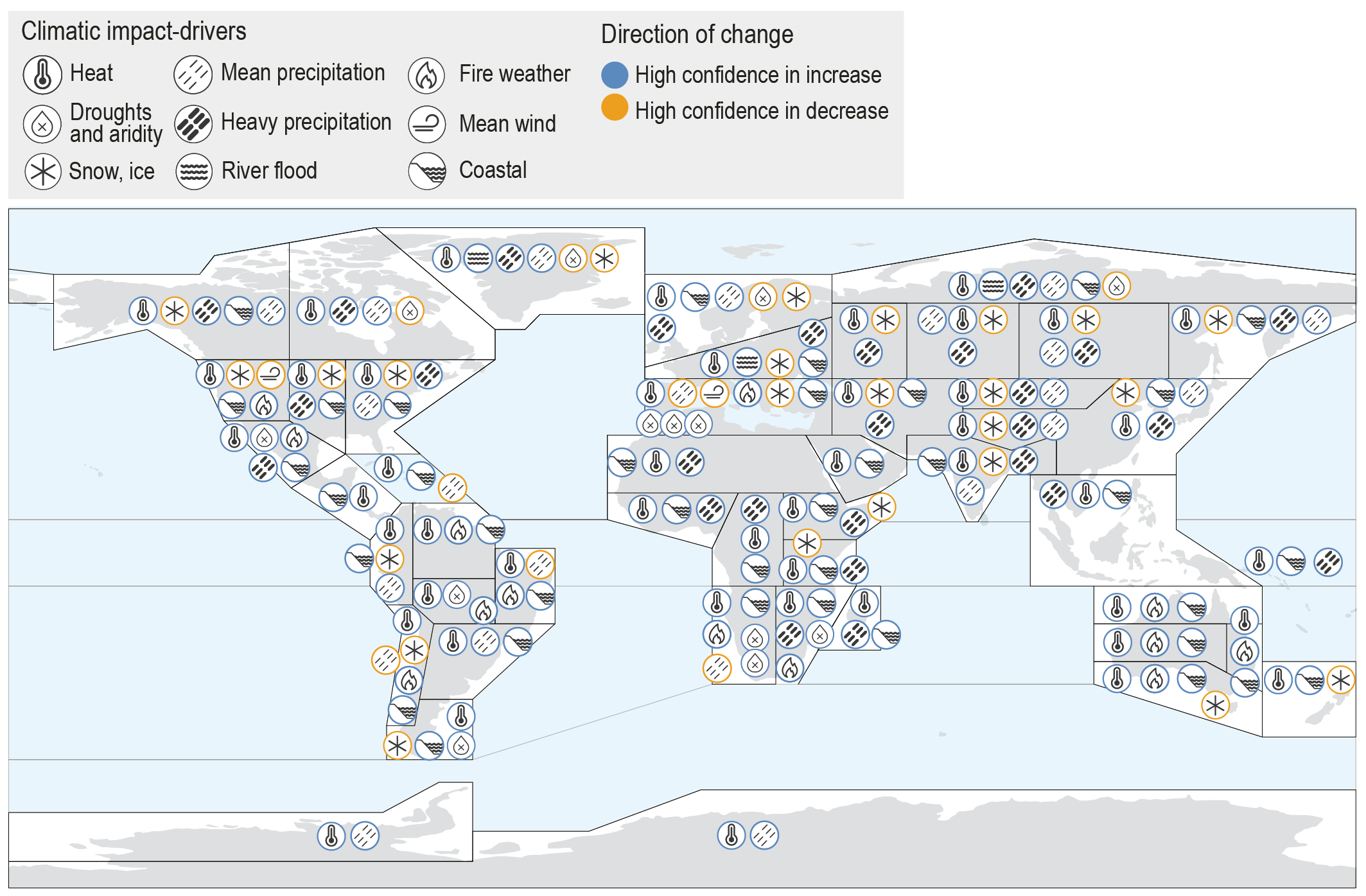

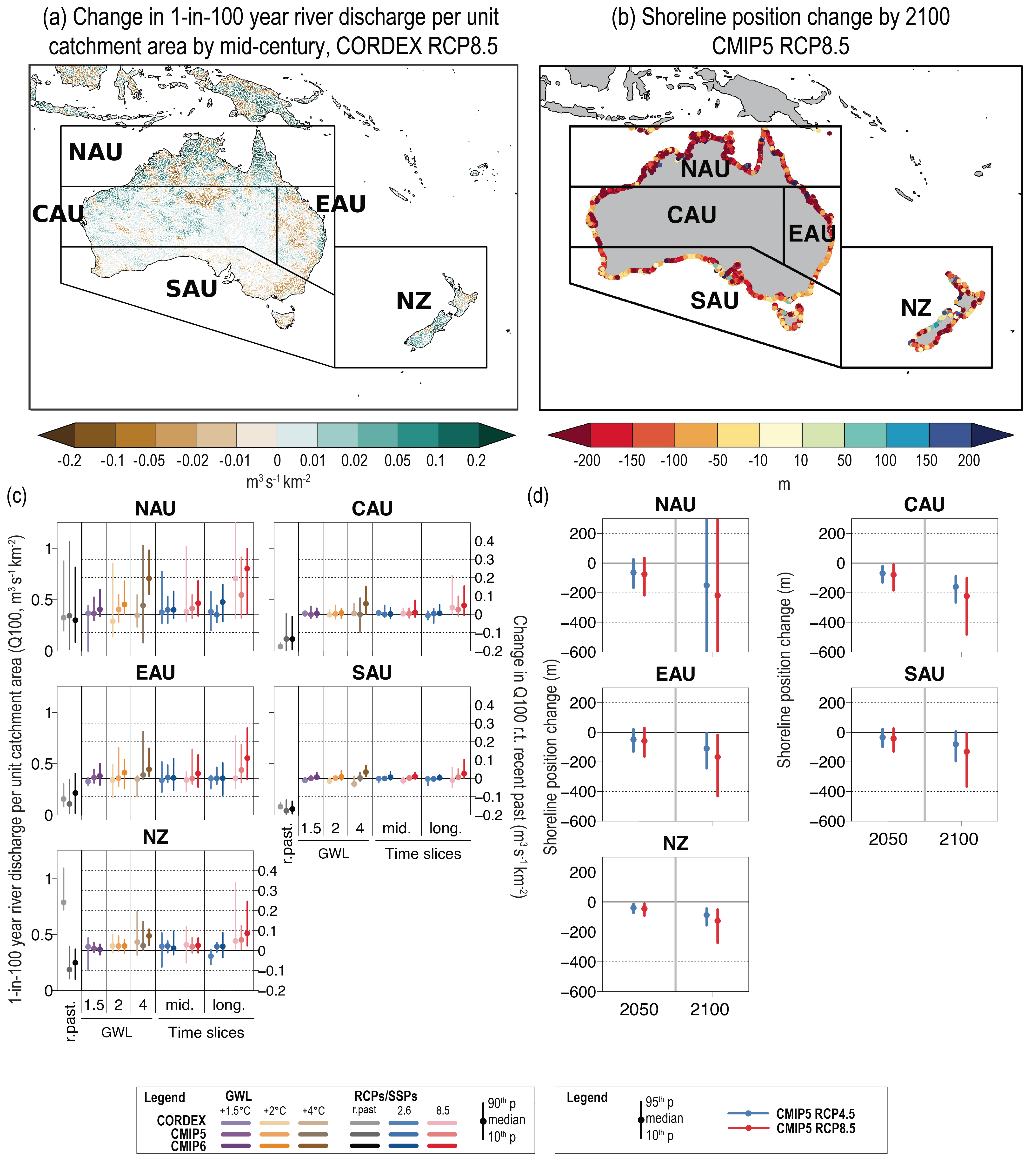

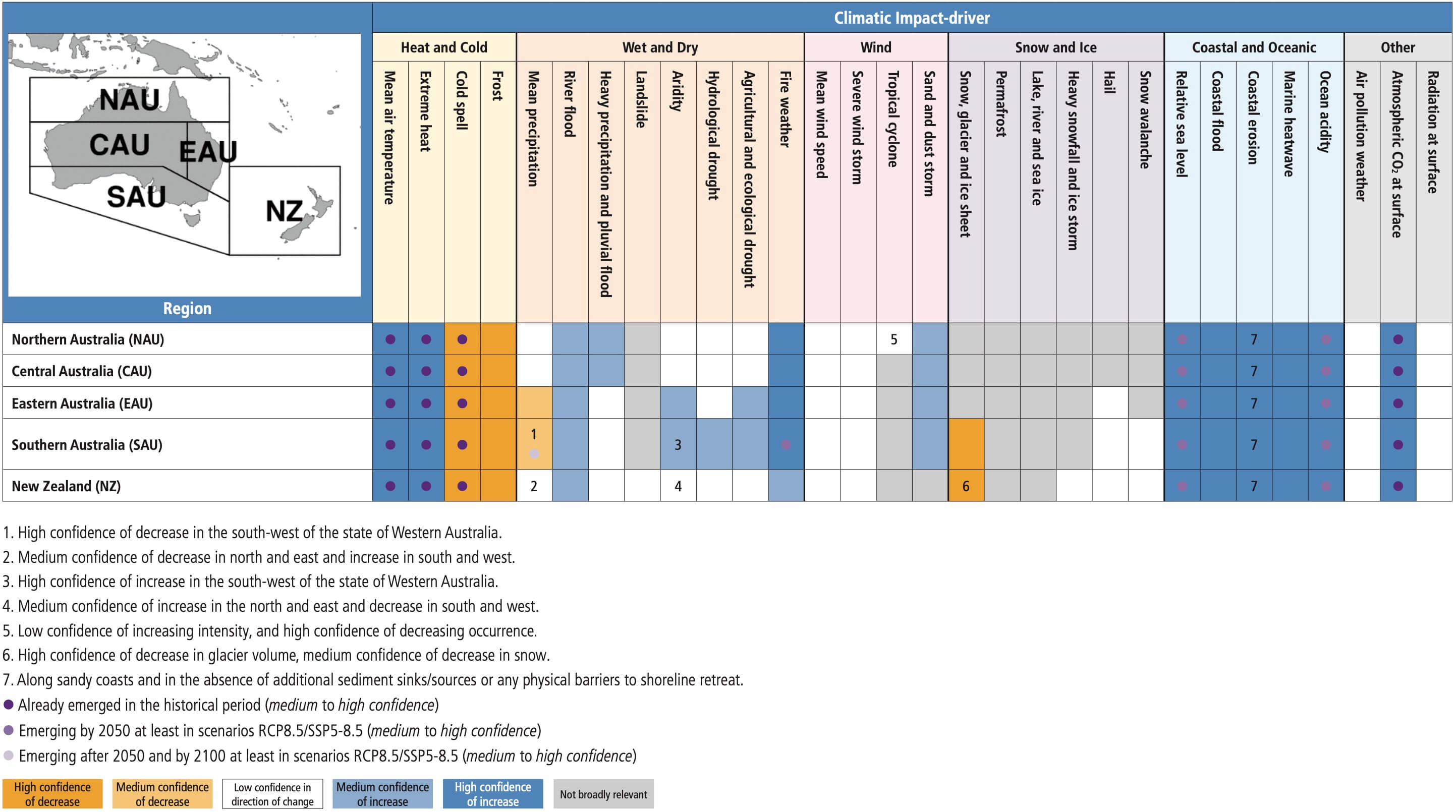

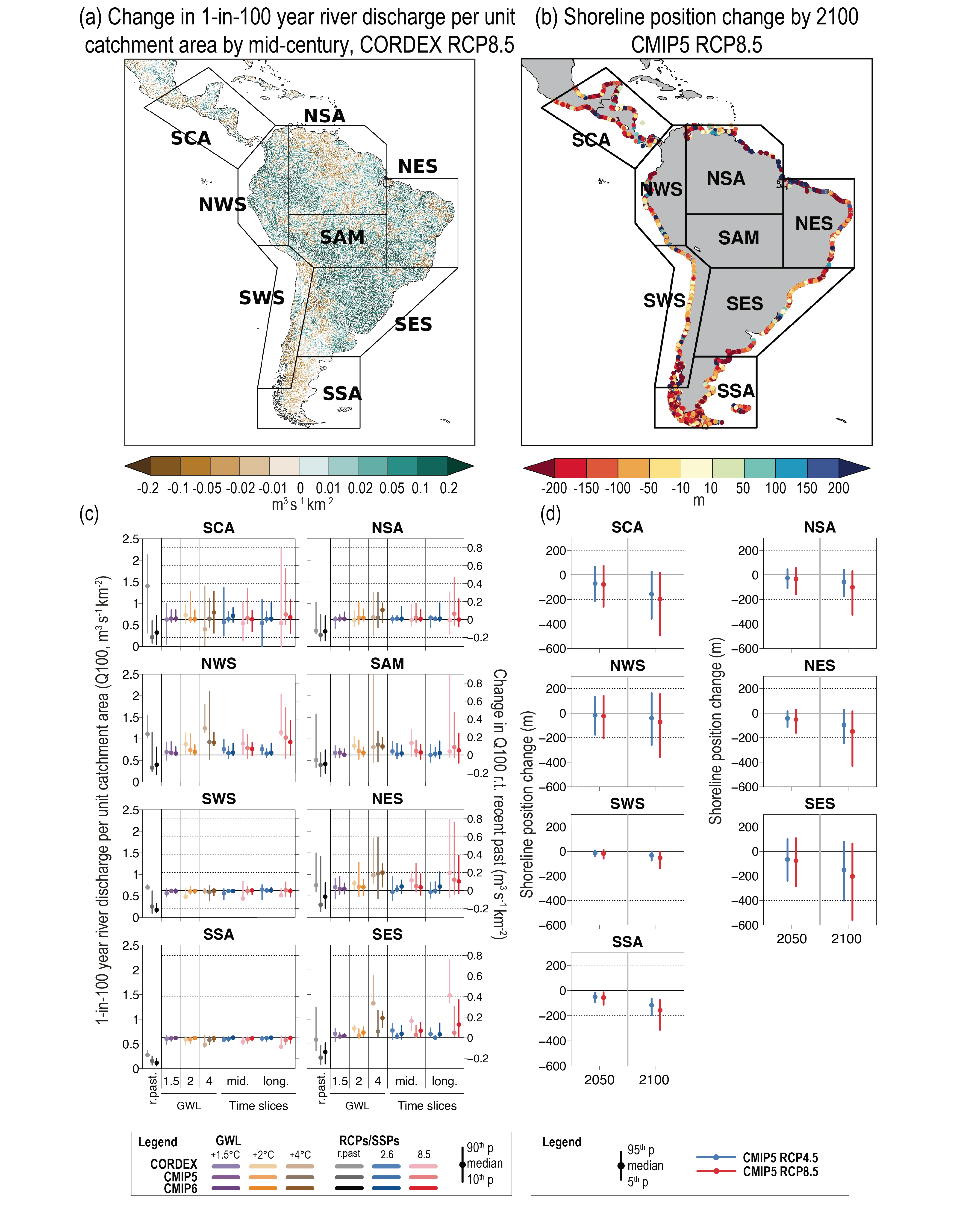

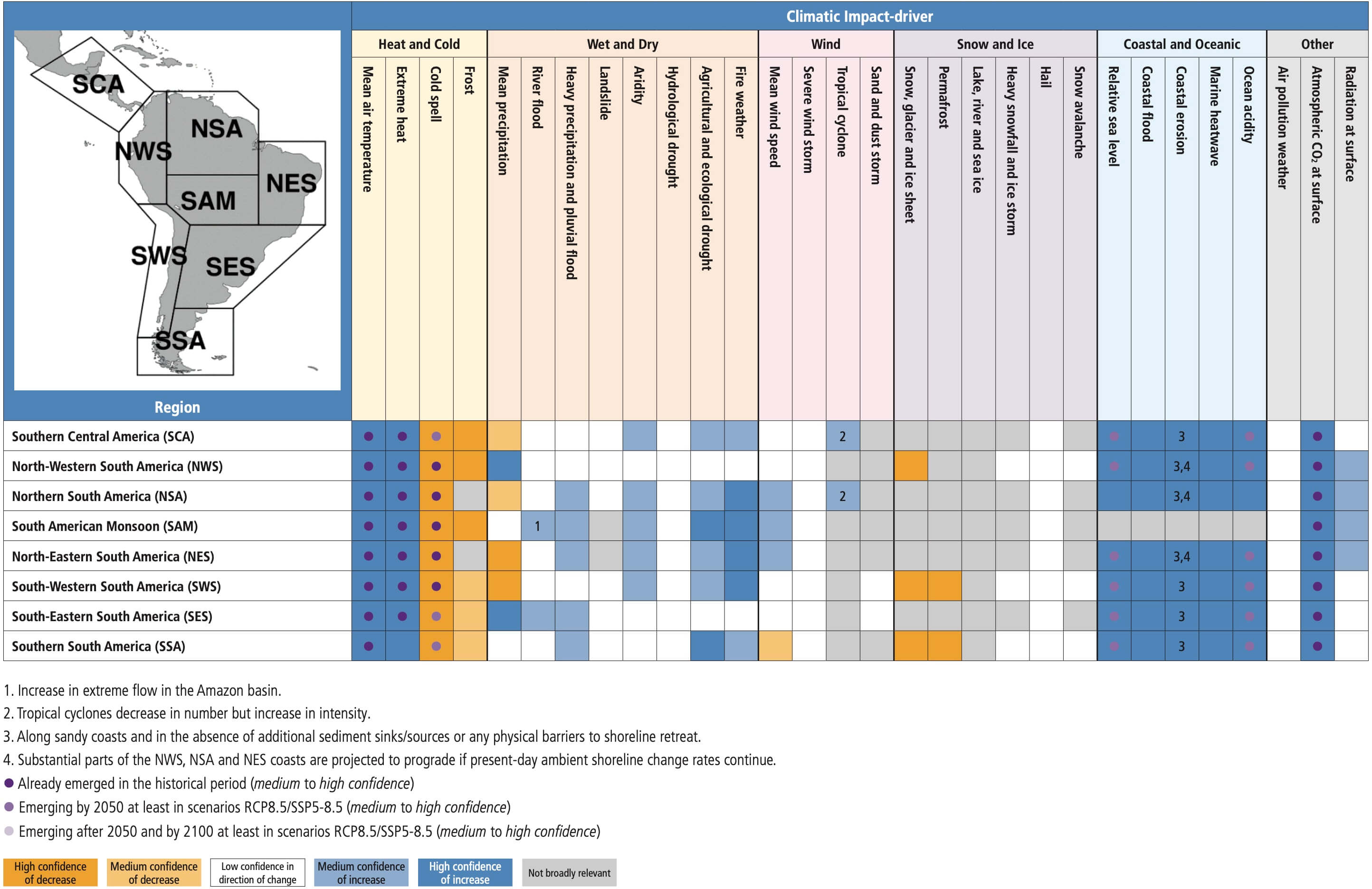

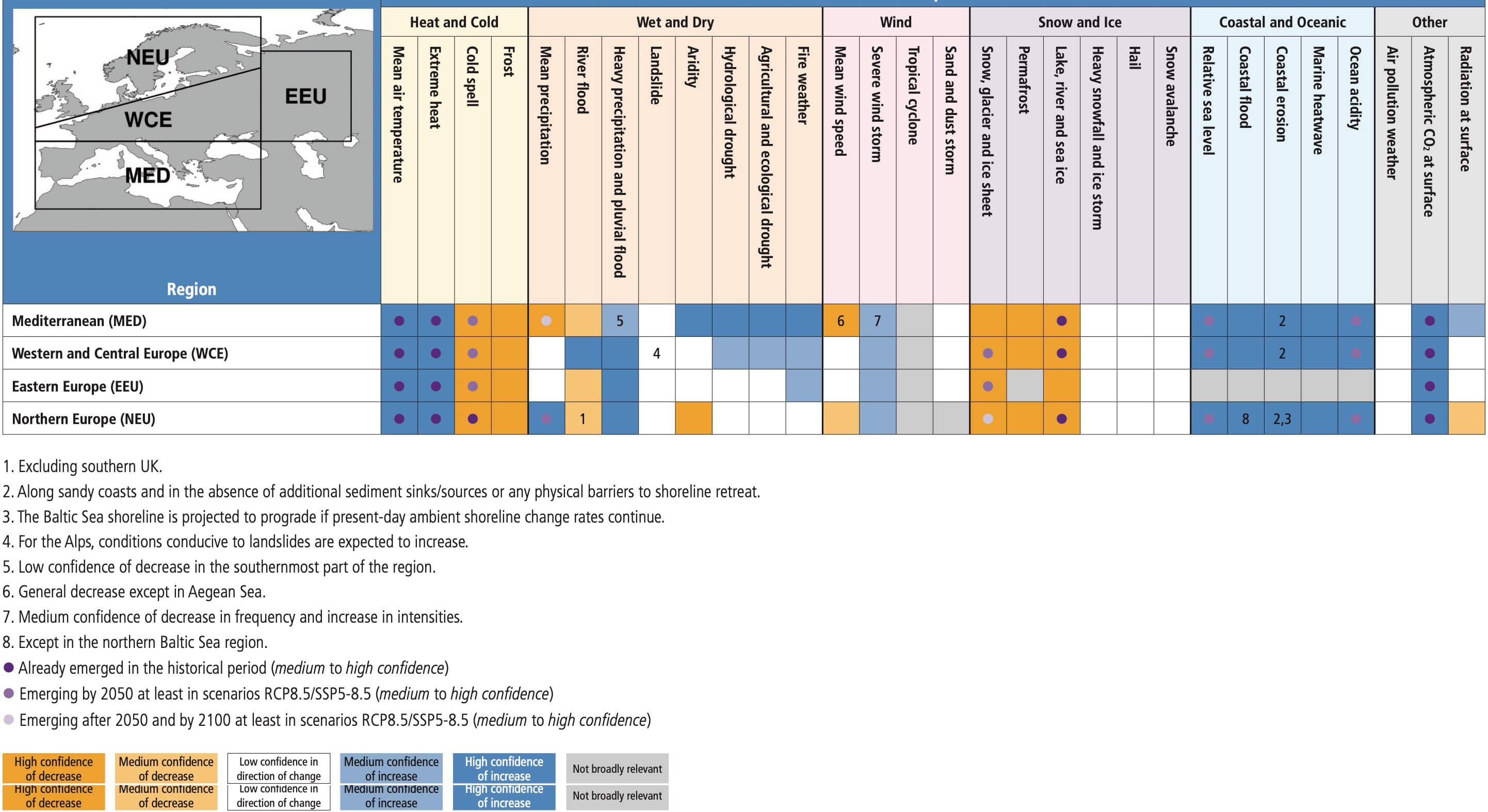

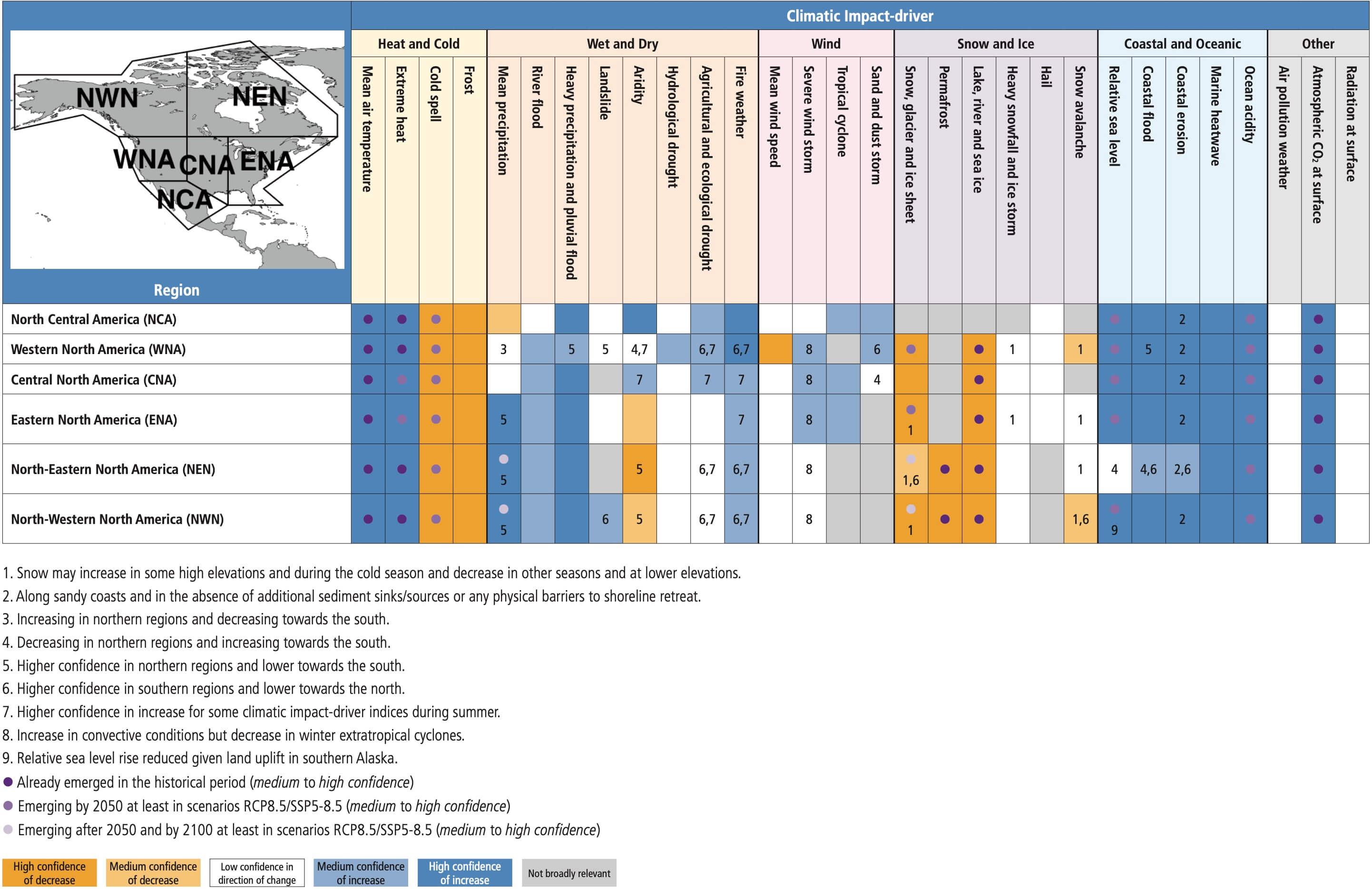

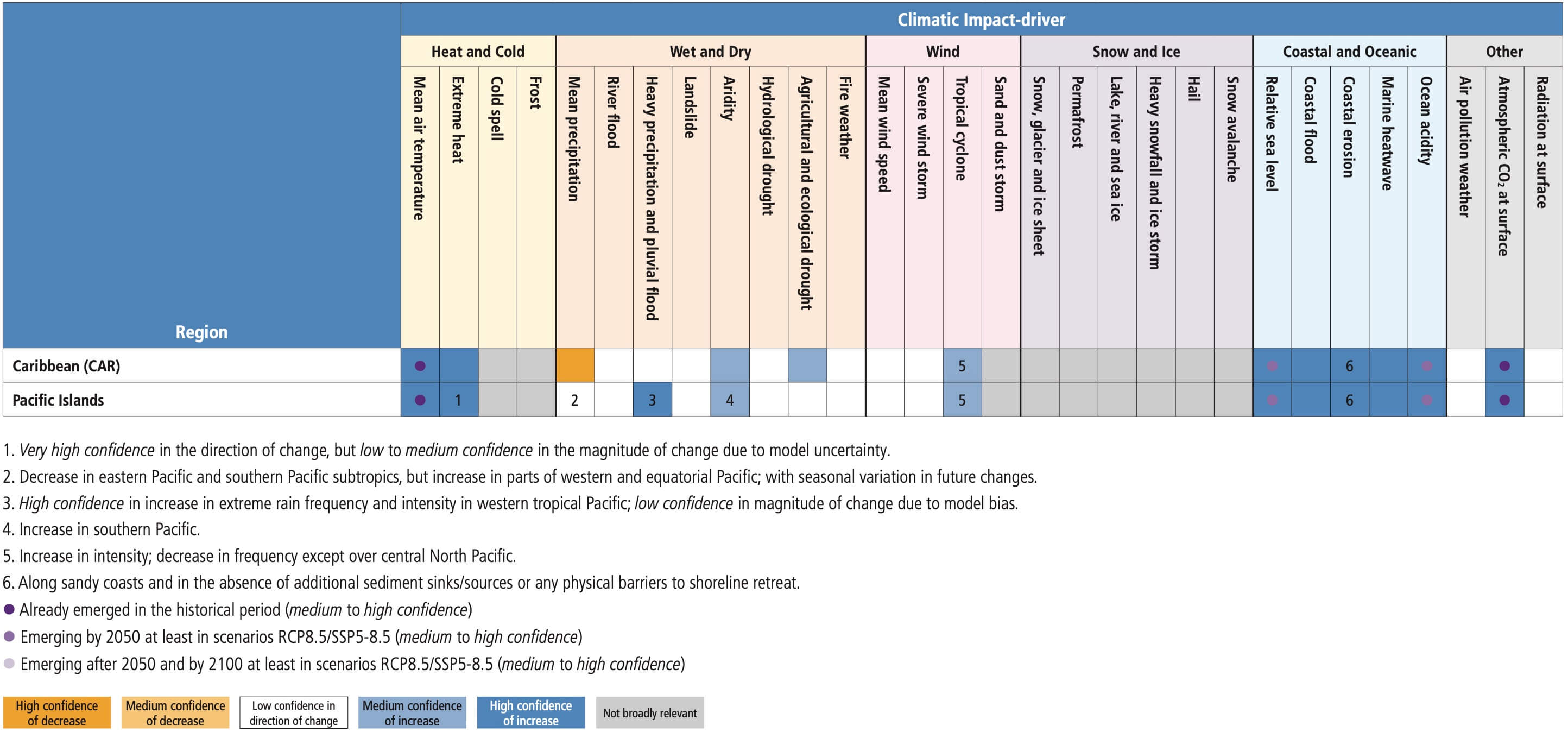

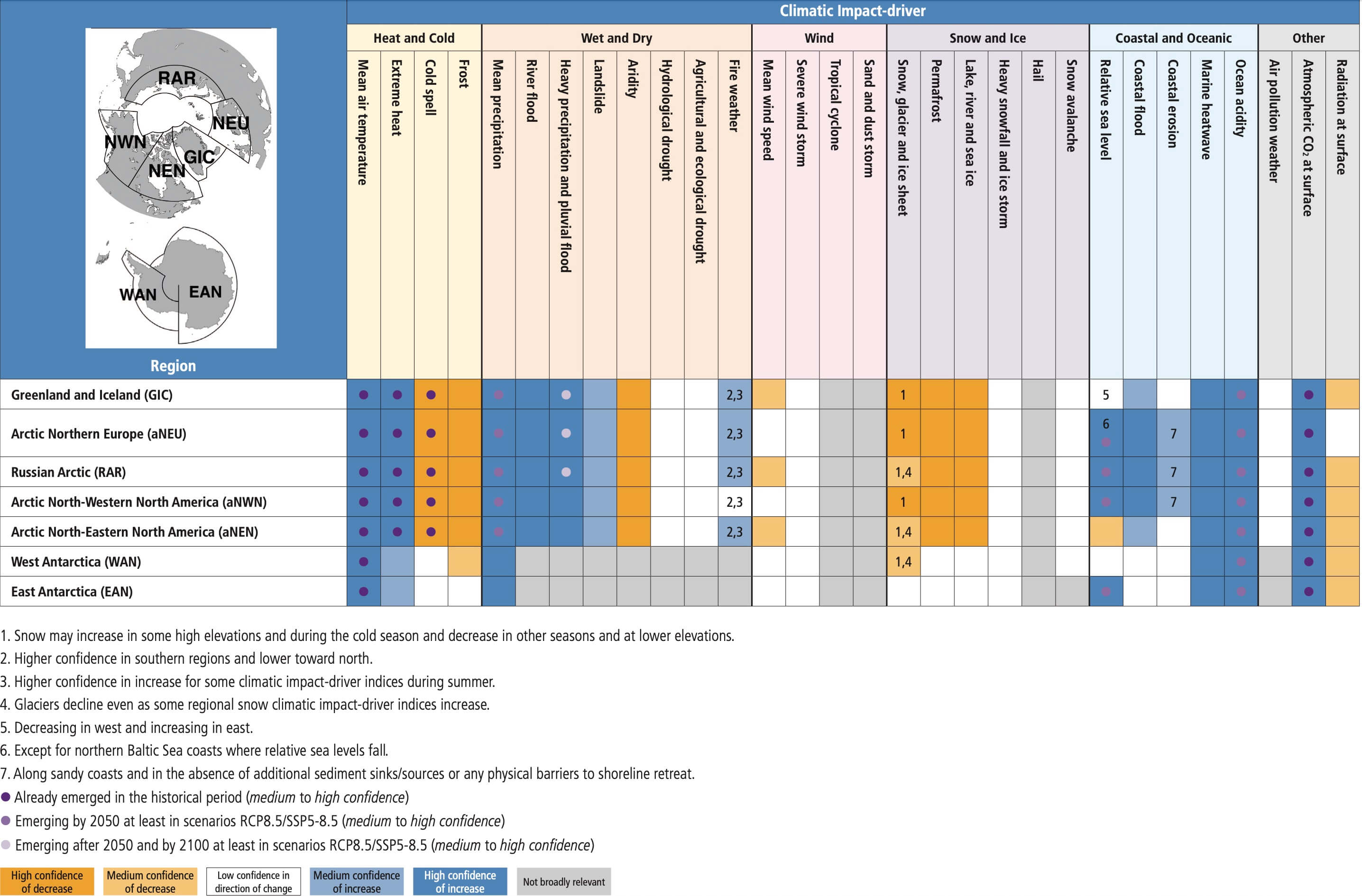

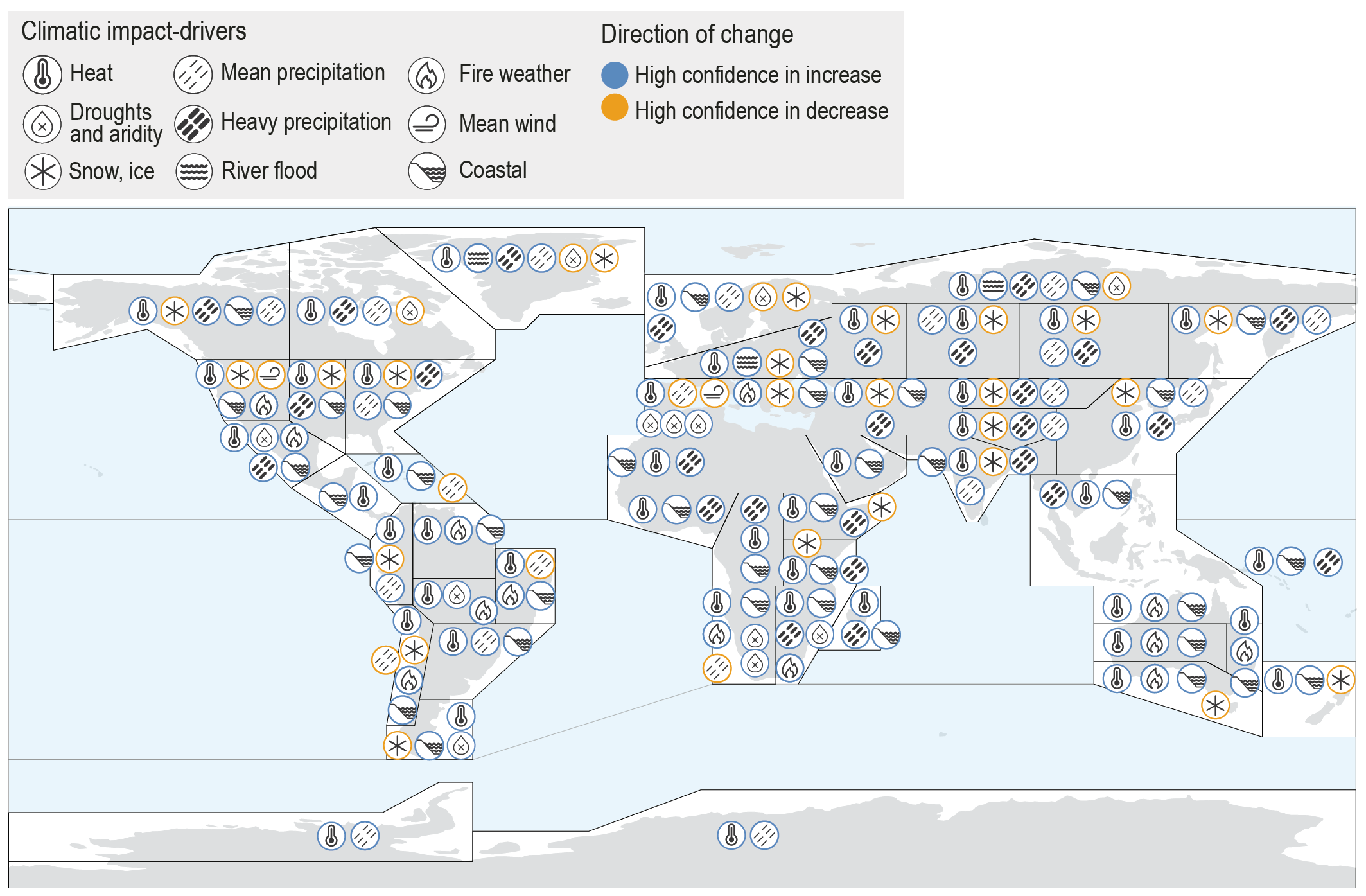

Every region of the world will experience concurrent changes in multiple CIDs by mid-century (high confidence), challenging the resilience and adaptation capacity of the region. Changes in heat, cold, snow and ice, coastal, oceanic, and CO2 at surface CIDs are projected with high confidence in most regions, indicating worldwide challenges, while additional region-specific changes are projected in other CIDs that may lead to more regional challenges. High confidence increases in some of the drought, aridity and fire weather CIDs will challenge, for example, agriculture, forestry, water systems, health and ecosystems in Southern Africa, the Mediterranean, North Central America, Western North America, the Amazon regions, South-Western South America, and Australia. High confidence changes in snow, ice and pluvial or river flooding will pose challenges for, for example, energy production, river transportation, ecosystems, infrastructure and winter tourism in North America, Arctic regions, Andes regions, Europe, Siberia, Central, South and East Asia, Southern Australia and New Zealand. Only a few CIDs are projected to change with high confidence in the Sahara, Madagascar, Arabian Peninsula, Western Africa and Small Islands; however, the lower confidence levels for CID changes in these regions can originate from knowledge gaps or model uncertainties, and does not necessarily mean that these regions have relatively low risk. {12.5}

Worldwide changes in heat, cold, snow and ice, coastal, oceanic and CO2-related CIDs will continue over the 21st century, albeit with regionally varying rates of change, regardless of the climate scenario (high confidence). In all regions there is high confidence that, by 2050, mean temperature and heat extremes will increase, and there is high confidence that sea surface temperature will increase in all oceanic regions except the North Atlantic. Apart from a few regions with substantial land uplift, relative sea level rise is very likely to virtually certain (depending on the region) to continue in the 21st century, contributing to increased coastal flooding in most low-lying coastal areas (high confidence) and coastal erosion along most sandy coasts (high confidence), while ocean acidification is virtually certain to increase. It is virtually certain that atmospheric CO2 at the surface will increase in all emissions scenarios until net zero emissions are achieved. Glaciers will continue to shrink and permafrost to thaw in all regions where they are present (high confidence). These changes will lead to climate states with no recent analogue that are of particular importance for specific regions such as tropical forests or biodiversity hotspots. {12.4}

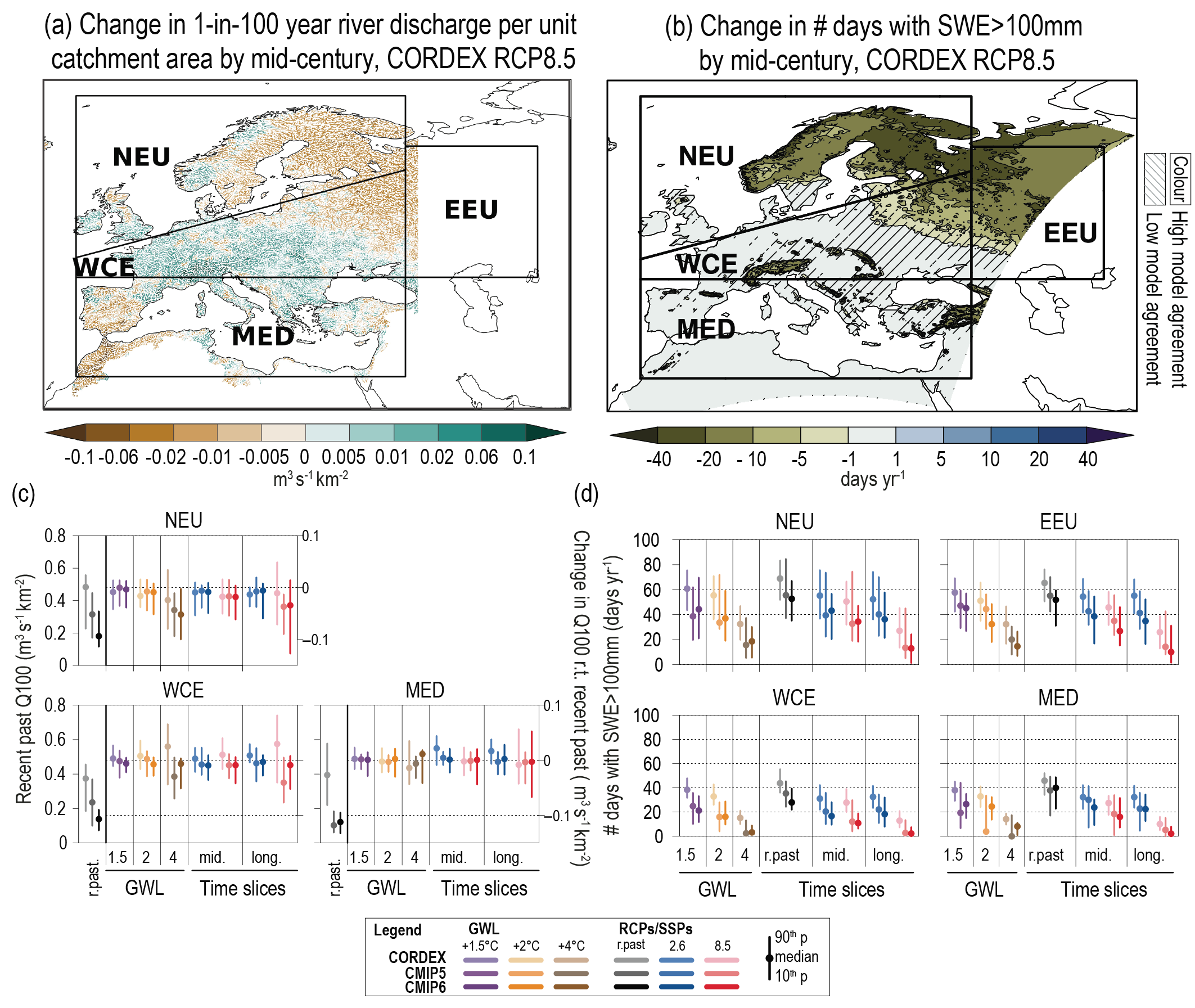

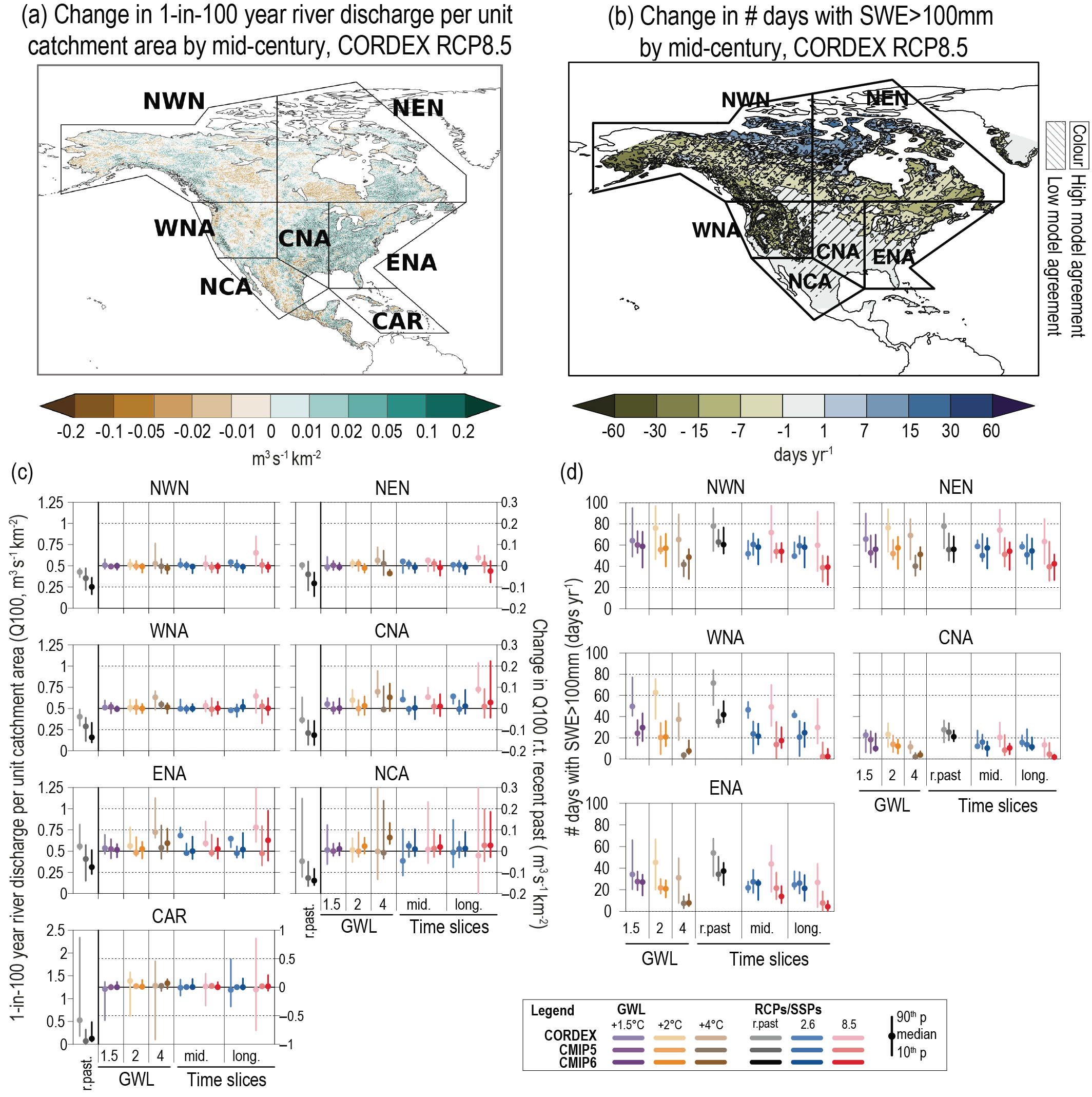

A wide range of region-specific CID changes relative to recent past are expected with high ormedium confidence, by 2050 and beyond. Most of these changes concern CIDs related to the water cycle and storms. Agricultural and ecological drought changes are generally of higher confidence than hydrological drought changes, with increases projected in North and Southern Africa, Madagascar, Southern and Eastern Australia, some regions of Central and South America, Mediterranean Europe, Western North America and North Central America (medium to high confidence). Fire weather conditions will increase by 2050 under RCP4.5 or above in several regions in Africa, Australia, several regions of South America, Mediterranean Europe, and North America (medium to high confidence). Extreme precipitation and pluvial flooding will increase in many regions around the world (high confidence). Increases in river flooding are also expected in Western and Central Europe and in polar regions (high confidence), most of Asia, Australasia, North America, the South American Monsoon region and South-Eastern South America (medium confidence). Mean winds are projected to slightly decrease by 2050 over much of Europe, Asia and Western North America, and increase in many parts of South America except Patagonia, West and South Africa and the eastern Mediterranean (medium confidence). Extratropical storms are expected to have a decreasing frequency but increasing intensity over the Mediterranean, increasing intensity over most of North America, and an increase in both intensity and frequency over most of Europe (medium confidence). Enhanced convective conditions are expected in North America (medium confidence). Tropical cyclones are expected to increase in intensity despite a decrease in frequency in most tropical regions (medium confidence). Climate change will modify multiple CIDs over Small Islands in all ocean basins, most notably those related to heat, aridity and droughts, tropical cyclones and coastal impacts. {12.4}

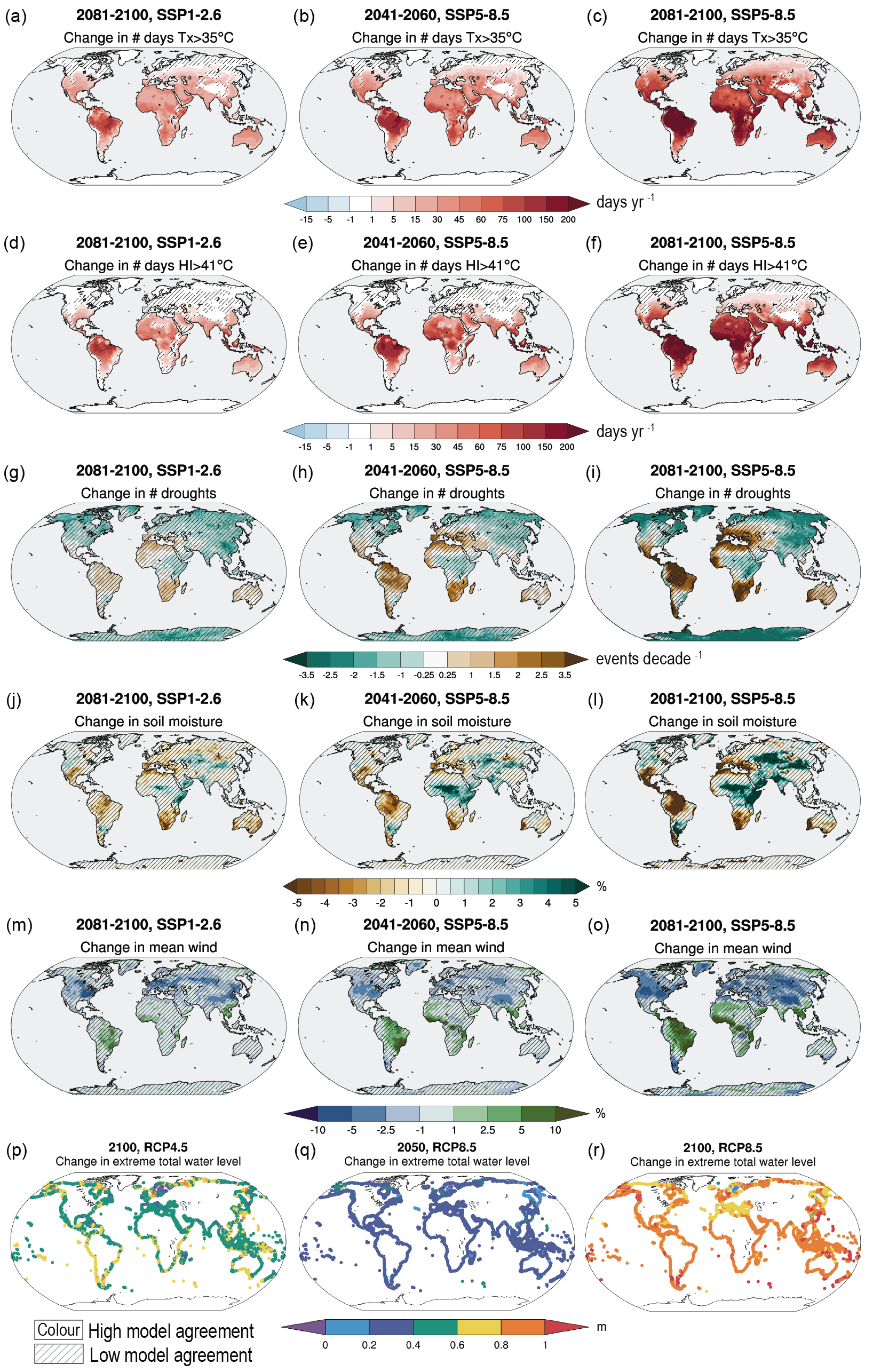

The level of confidence in the projected direction of change in CIDs and the intensity of the signal depend on mitigation efforts over the 21st century, as reflected by the differences between end-century projections for different climate scenarios. Dangerous humid heat thresholds, such as the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Heat Index (NOAA HI) of 41°C, will be exceeded much more frequently under the SSP5-8.5 scenario than under SSP1-2.6 and will affect many more regions (high confidence). In many tropical regions, the number of days per year where an HI of 41°C is exceeded will increase by more than 100 days relative to the recent past under SSP5-8.5, while this increase will be limited to less than 50 days under SSP1-2.6 (high confidence). The number of days per year where temperature exceeds 35°C will increase by more than 150 days in many tropical areas, such as the Amazon basin and South East Asia under SSP5-8.5, while it is expected to increase by less than two months in these areas under SSP1-2.6 (except for the Amazon Basin). There is high confidence that sandy shorelines will retreat in most regions of the world, in the absence of additional sediment sources or physical barriers to shoreline retreat. The total length of sandy shorelines around the world that are projected to retreat by more than 100 m by the end of the century is about 35% greater under RCP8.5 (about 130,000 km) compared to that under RCP 4.5 (about 95,000 km). The frequency of the present-day 1-in-100 year extreme sea level event (represented here by extreme total water level) is also projected to increase substantially in most regions (high confidence). In a globally averaged sense, the 1-in-100 year extreme sea level is projected to become an event that occurs multiple times per year under RCP8.5, while under RCP4.5 it is projected to become a one-in-five-year event, representing at least a five fold increase from RCP4.5 to RCP8.5. {12.4, 12.5}

There is low confidence in past and future changes of several CIDs. In nearly all regions there is low confidence in changes in hail, ice storms, severe storms, dust storms, heavy snowfall and avalanches, although this does not indicate that these CIDs will not be affected by climate change. For such CIDs, observations are short term or lack homogeneity, and models often do not have sufficient resolution or accurate parametrization to adequately simulate them over climate change time scales. {12.4}

Many global- and regional-scale CIDs have a direct relation to global warming levels (GWLs) and can thus inform the hazard component of ‘Representative Key Risks’ and ‘Reasons for Concern’ assessed by AR6 WGII. These include both mean and extreme heat, cold, wet and dry hazards; cryospheric hazards (snow cover, ice extent, permafrost); and oceanic hazards (marine heatwaves) (high confidence). For some of these, a quantitative relation can be drawn (high confidence). For example, with each degree of global surface air temperature (GSAT) warming, the magnitude and intensity of many heat extremes show a linear change, while some changes in frequency of threshold exceedances are exponential: Arctic temperatures warm about twice as fast as GSAT; global sea surface temperatures increase by about 80% of GSAT change; Northern Hemisphere spring snow cover decreases by about 8% per 1°C. For other hazards (e.g., ice-sheet behaviour, glacier mass loss, global mean sea level rise, coastal floods and coastal erosion) the time and/or scenario dimensions remain critical and a simple relation with GWLs cannot be drawn (high confidence), but still quantitative estimates assuming specific time frames and/or stabilized GWLs can be derived (medium confidence). Model uncertainty challenges the link between specific GWLs and tipping points and irreversible behaviour, but their occurrence cannot be excluded and their chances increase with warming levels (medium confidence). {CCB 12.1}

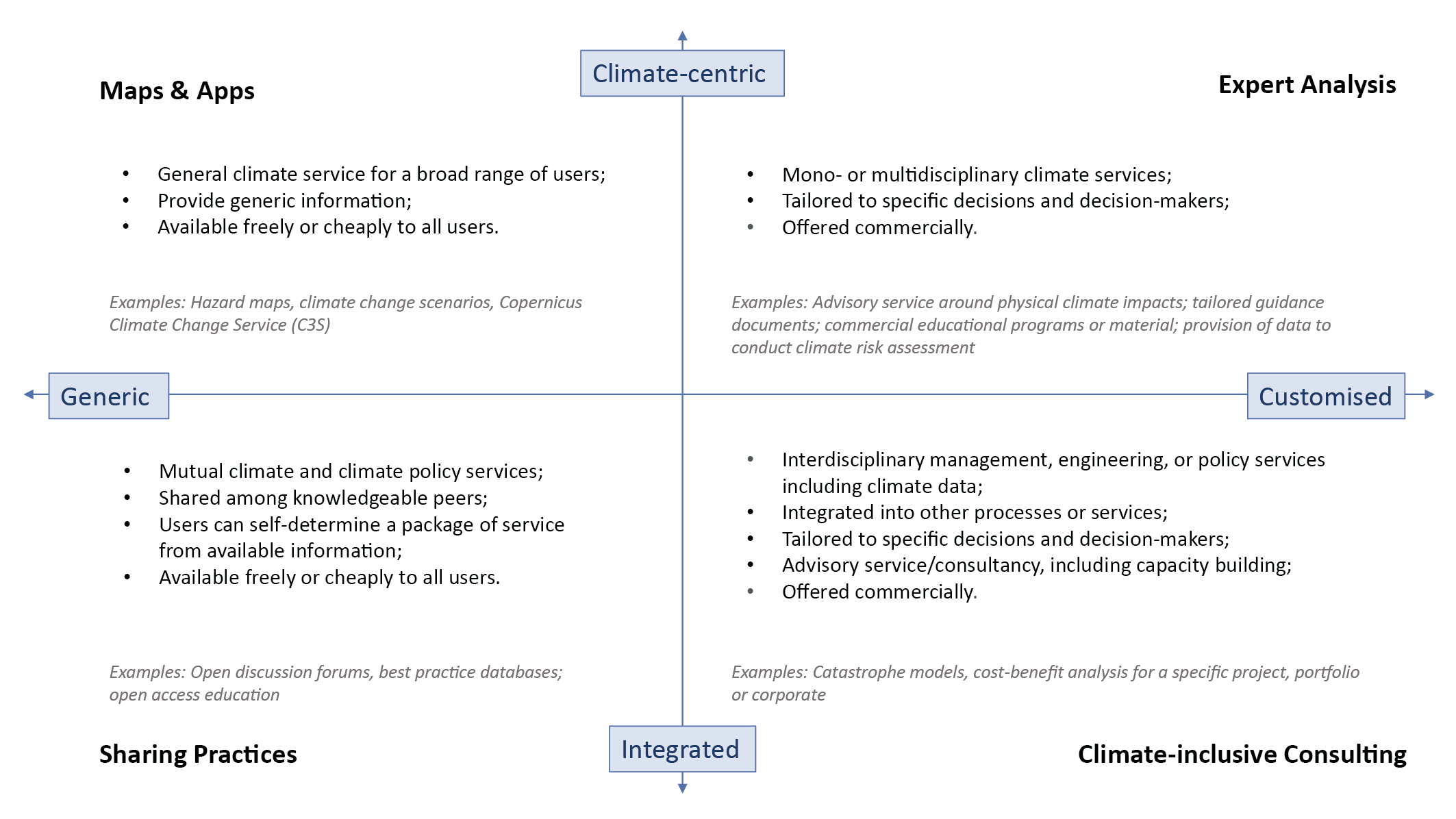

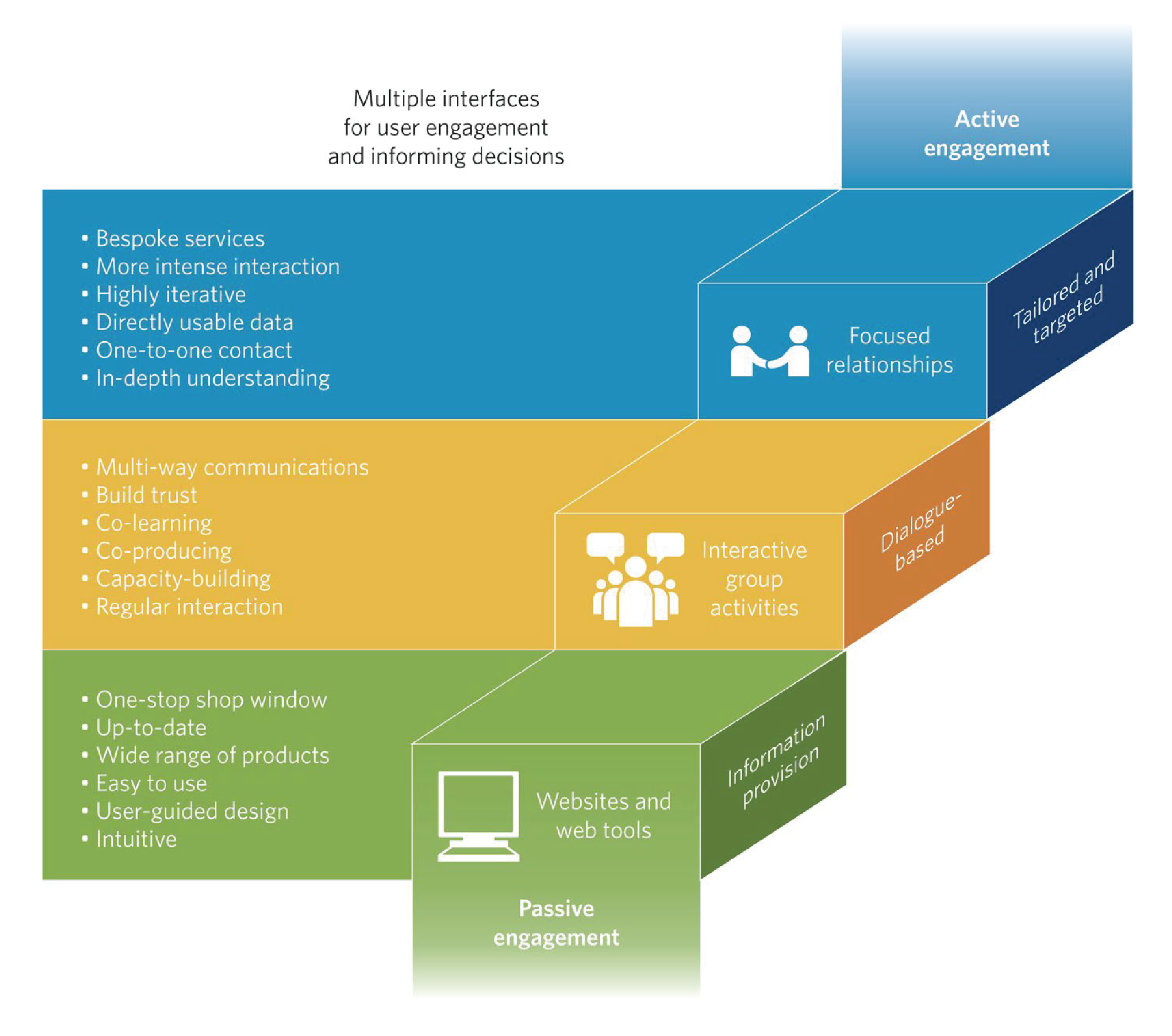

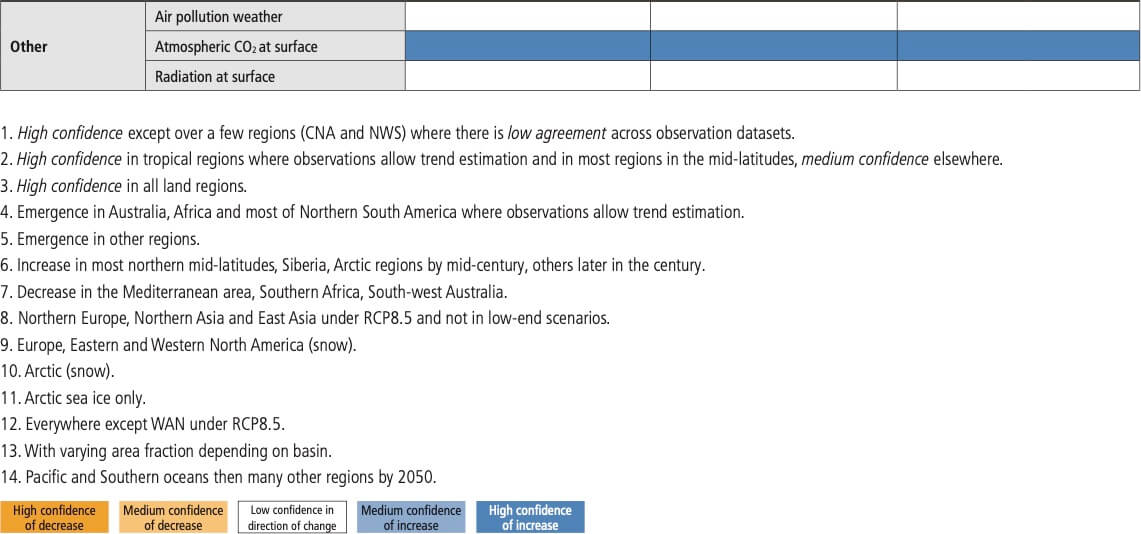

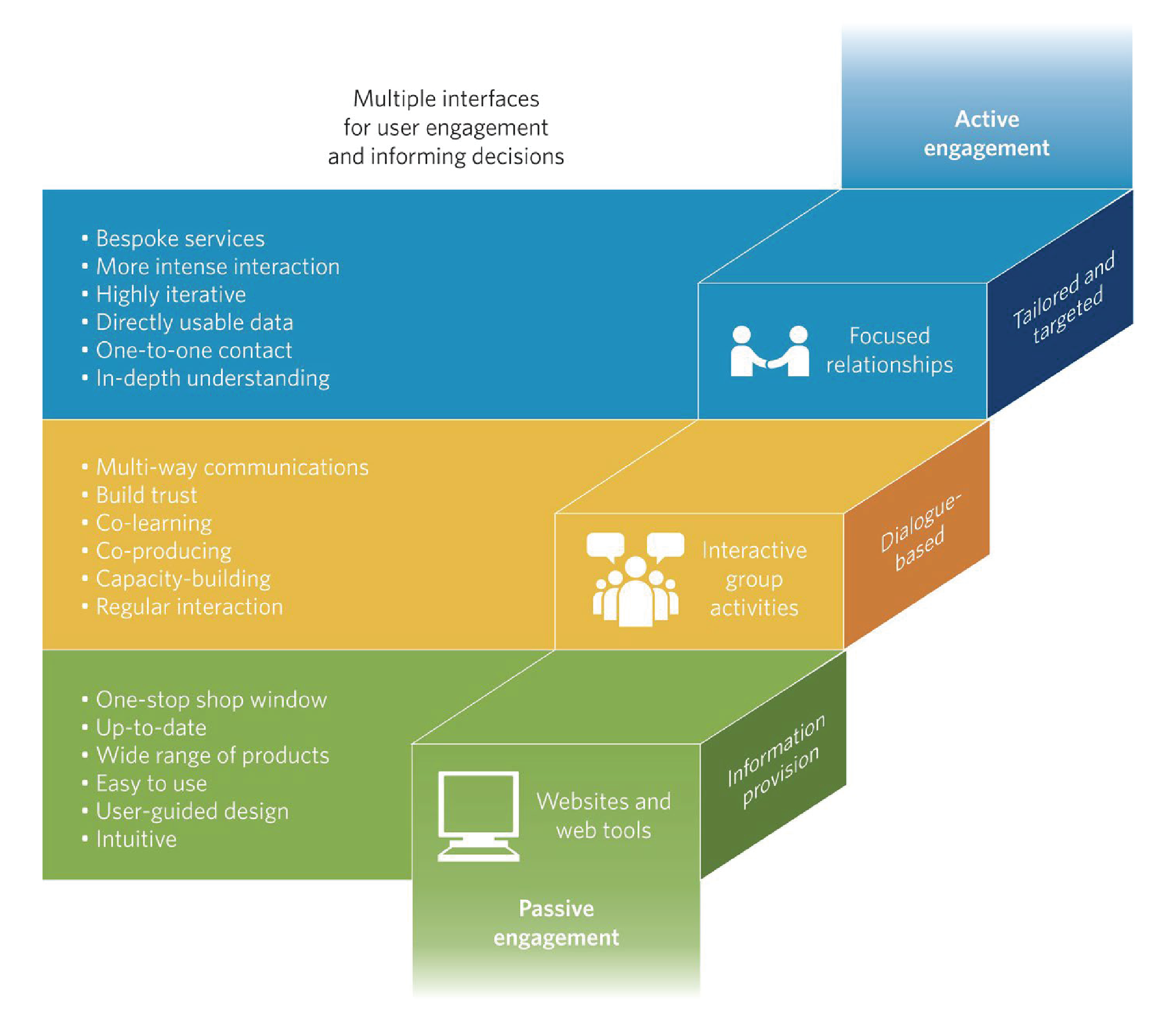

Since AR5, climate change information produced in climate service contexts has increased significantly due to scientific, technological advancements and growing user demand (very high confidence). Climate services involve the provision of climate information in such a way as to assist decision-making. These services include appropriate engagement from users and providers, are based on scientifically credible information and expertise, have an effective access mechanism, and respond to user needs. Climate services are being developed across regions, sectors, time scales and target users. {12.6}

Climate services are growing rapidly and are highly diverse in their practices and products (very high confidence). The decision-making context, level of user engagement and co-production between scientists, practitioners and intended users are important determinants of the type of climate service developed and its utility supporting adaptation, mitigation and risk management decisions. User needs and decision-making contexts are very diverse and there is no universal approach to climate services. {12.6}

Realization of the full potential of climate services is often hindered by limited resources for the co-design and co-product ion process, including sustained engagement between scientists, service providers and users (high confidence). Further challenges relate to climate services development, provision of climate services, generation of climate service products, communication with users, and evaluation of the quality and socio-economic value of climate services. The development of climate services often uncovers and presents new research challenges to the scientific community. {12.6}

12.1 Framing

Climate change is already resulting in significant societal and environmental impacts and will induce major socio-economic damages in the future (AR5 WGII). The society, at large, benefits from information related to climate change risks, which enables the development of options to protect lives, preserve nature, build resilience and prevent avoidable loss and damage. Climate change can also lead to beneficial conditions that can be taken into account in adaptation strategies.

This chapter assesses climate change information relevant for regional impact and for risk assessment. It complements other WGI chapters that focus on the physical processes determining changes in the climate system and on methods for estimating regional changes.

Impacts of climate change are driven not only by changes in climate conditions, but also by changes in exposure and vulnerability (Cross-Chapter Box 1.3). This chapter concentrates on drivers of impacts that are of climatic origin (see also the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR1.5, IPCC, 2018), and Section 1.3.2 in this Report), referred to in WGI as ‘climatic impact-drivers’ (CIDs). CIDs are physical climate system conditions (e.g., means, events, extremes) that affect an element of society or ecosystems. Depending on system tolerance, CIDs and their changes can be detrimental, beneficial, neutral, or a mixture of each across interacting system elements and regions. However, this chapter largely focuses on drivers commonly connected to hazards, and adopts the IPCC risk framework (Cross-Chapter Box 1.3) since the main objective of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is to ‘prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’ (Article 2).

In some cases, risk assessments may require climate information beyond the CIDs identified in this chapter, with further impacts or risk modelling often driven by historical climate forcing datasets (e.g., Ruane et al., 2021) and full climate scenario time series (e.g., Lange, 2019) produced using methods described in Chapter 10. Chapter 12 focuses on the assessment of a finite number of drivers and how they are projected to evolve with climate change, in order to inform impact and risk assessments.

This chapter is new in IPCC WGI assessment reports, in that it represents a contribution to the ‘IPCC risk framework’. Within this framework, climate-related impacts and risks are determined through an interplay between the occurrence of climate hazards and their consequences depending on the exposure of the affected human or natural system and its vulnerability to the hazardous conditions. In Chapter 12, we are assessing climatic impact-drivers that could lead to hazards or to opportunities, from the literature and model results since AR5. This will particularly support the assessment of key risks related to climate change by WGII (Chapter 16). Despite the fact that impacts may also be induced by climate adaptation and mitigation policies themselves, as well as by socio-economic trends, changes in vulnerability or exposure, and external geophysical hazards such as volcanoes, the focus here is only on climatic impacts and risks induced by shifts in physical climate phenomena that directly influence human and ecological systems (Cross-chapter Box 1.3).

This chapter follows the terminology associated with the framing introduced in Chapter 1 (Cross-Chapter Box 1.2) and as found in Annex VII: Glossary. The highlighted terms below are introduced and used extensively in this chapter:

- Indices for climatic impact-drivers: numerically computable indices using one or a combination of climate variables designed to measure the intensity of the climatic impact-driver, or the probability of exceedance of a threshold. For instance, an index of heat inducing human health stress is the Heat Index (HI) that combines temperature and relative humidity (e.g., Burkart et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2012; Kent et al., 2014) and is used by the NOAA for issuing heat warnings.

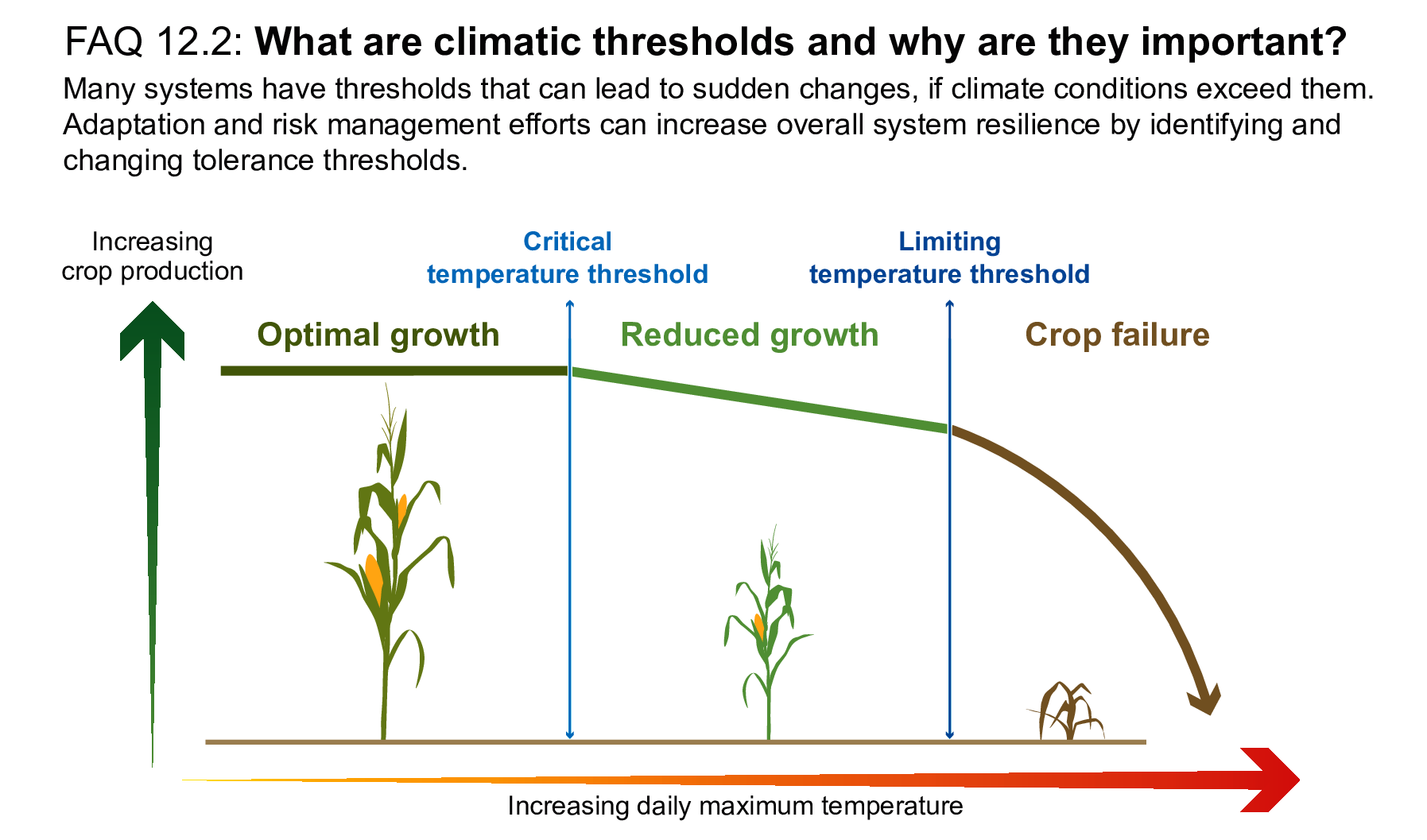

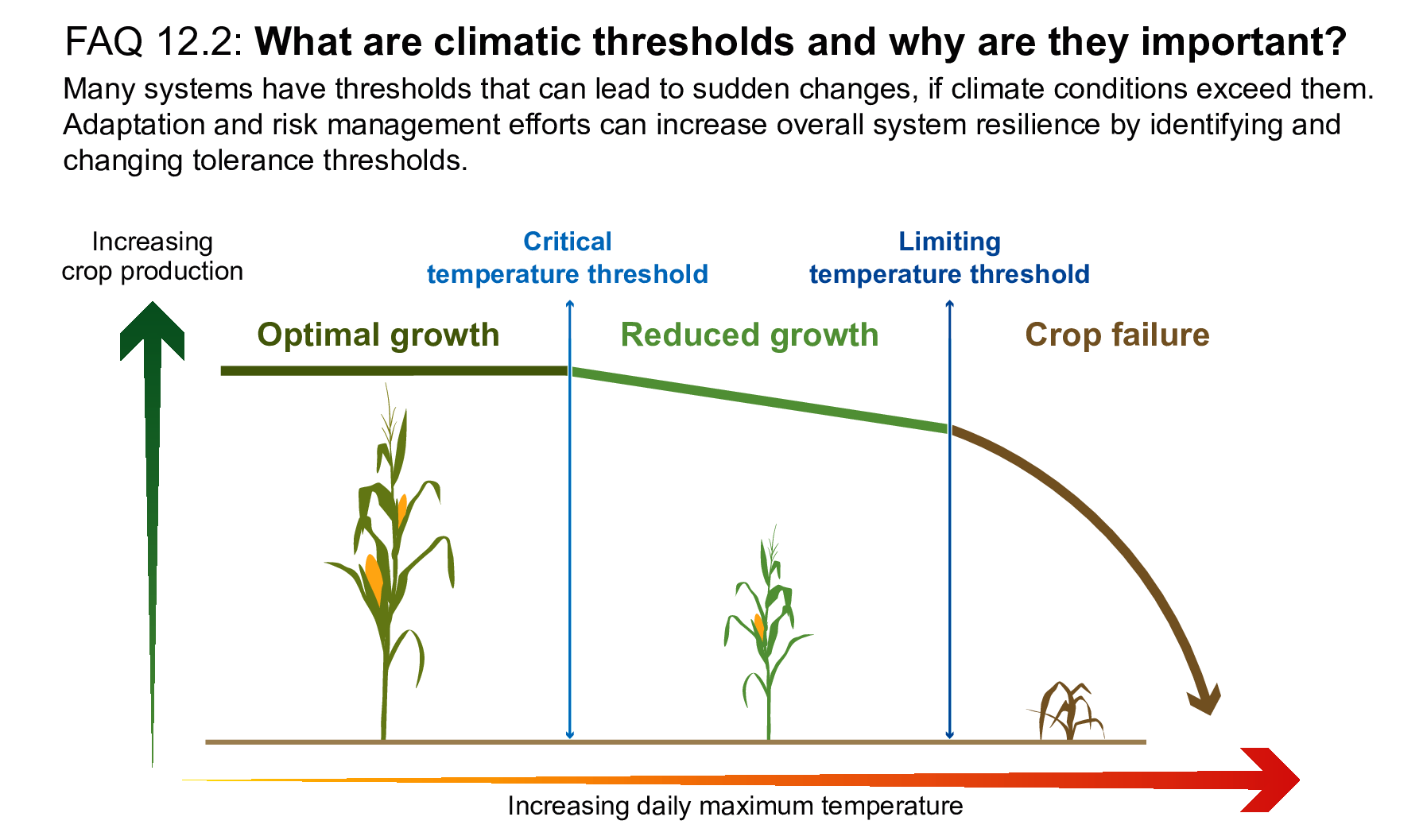

- Thresholds for climatic impact-drivers: an identified index value beyond which a climatic impact-driver interacts with vulnerability or exposure to create, increase or reduce an impact, risk or opportunity. Thresholds can be used to measure various aspects of the climatic impact-driver (magnitude or intensity, duration, frequency, timing, and spatial extent of threshold exceedance). For instance, a threshold of daily maximum temperature above 35°C is considered critical for maize pollination and production (e.g., Schauberger et al., 2017; Tesfaye et al., 2017).

The approach adopted here is consistent with the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, which aims to face disaster consequences (including but not limited to climate disasters) and reduce risks in natural, managed and built environments (Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2015; UNISDR, 2015). The classification of climatic impact-drivers in this chapter is largely consistent with the classification of hazards used in the Sendai Framework. However, the UNISDR hazard list spans a wider range of hazards inducing damage to society, including hazards that are not directly related to climate (such as volcanoes and earthquakes), which are excluded from the assessment herein. Furthermore, the UNISDR classification of hazards does not include mean climatic conditions, which are also discussed as climatic impact-drivers in this chapter. The first priority mentioned in the Sendai Framework is understanding disaster risk as a necessary step for action. Facilitating such an understanding is a clear goal of this chapter.

The chapter adopts a regional perspective (continental regions as defined in Chapter 1 and used in WGII; see Figure 1.18) on climatic impact-drivers to support decision-making across a wide audience of global and regional stakeholders in addition to governments (e.g., civil society organizations, public and private sectors, academia). While the focus here is on future changes, it also describes current levels and observed trends of CIDs as an important point of reference for informing adaptation strategies.

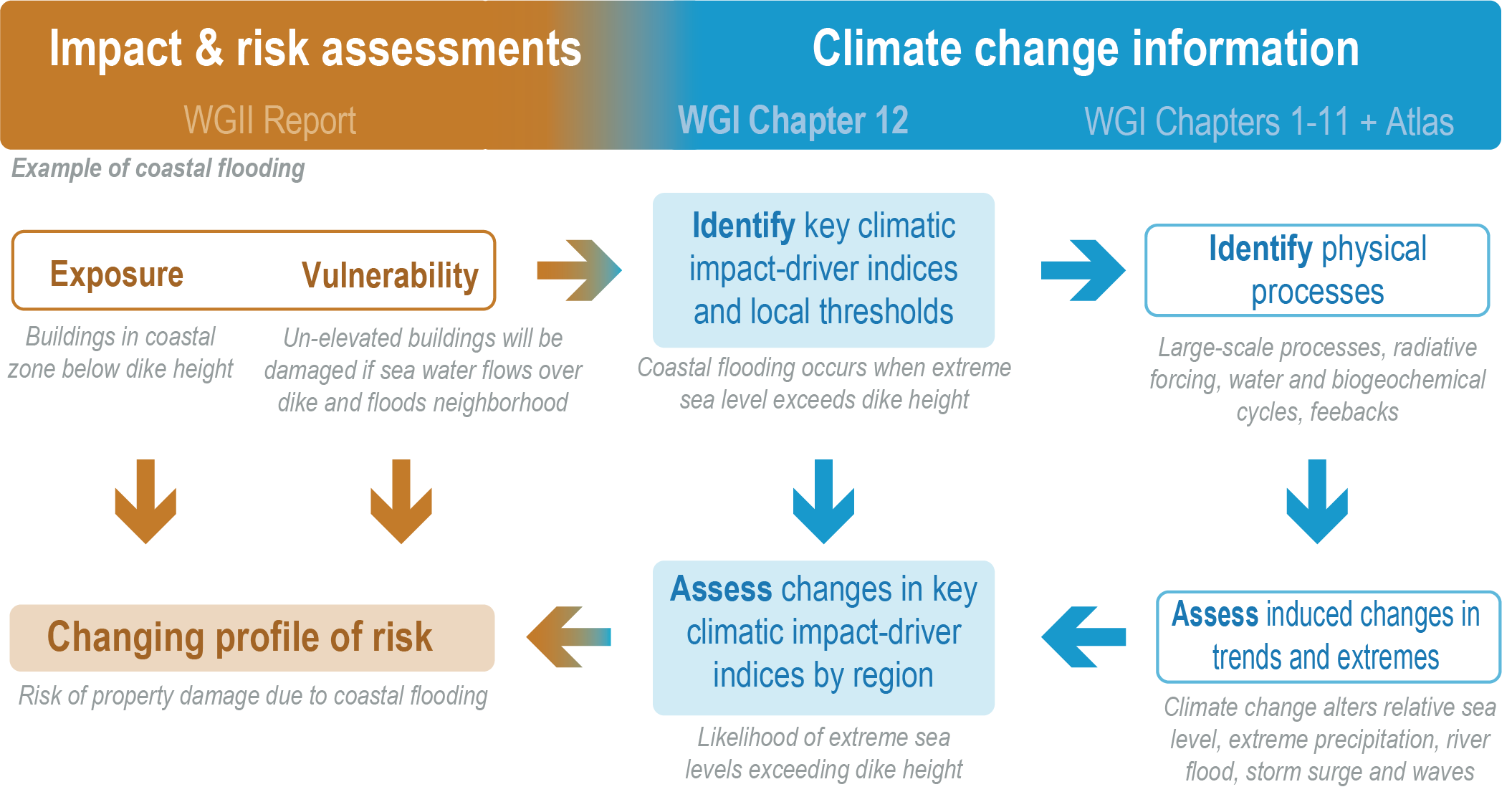

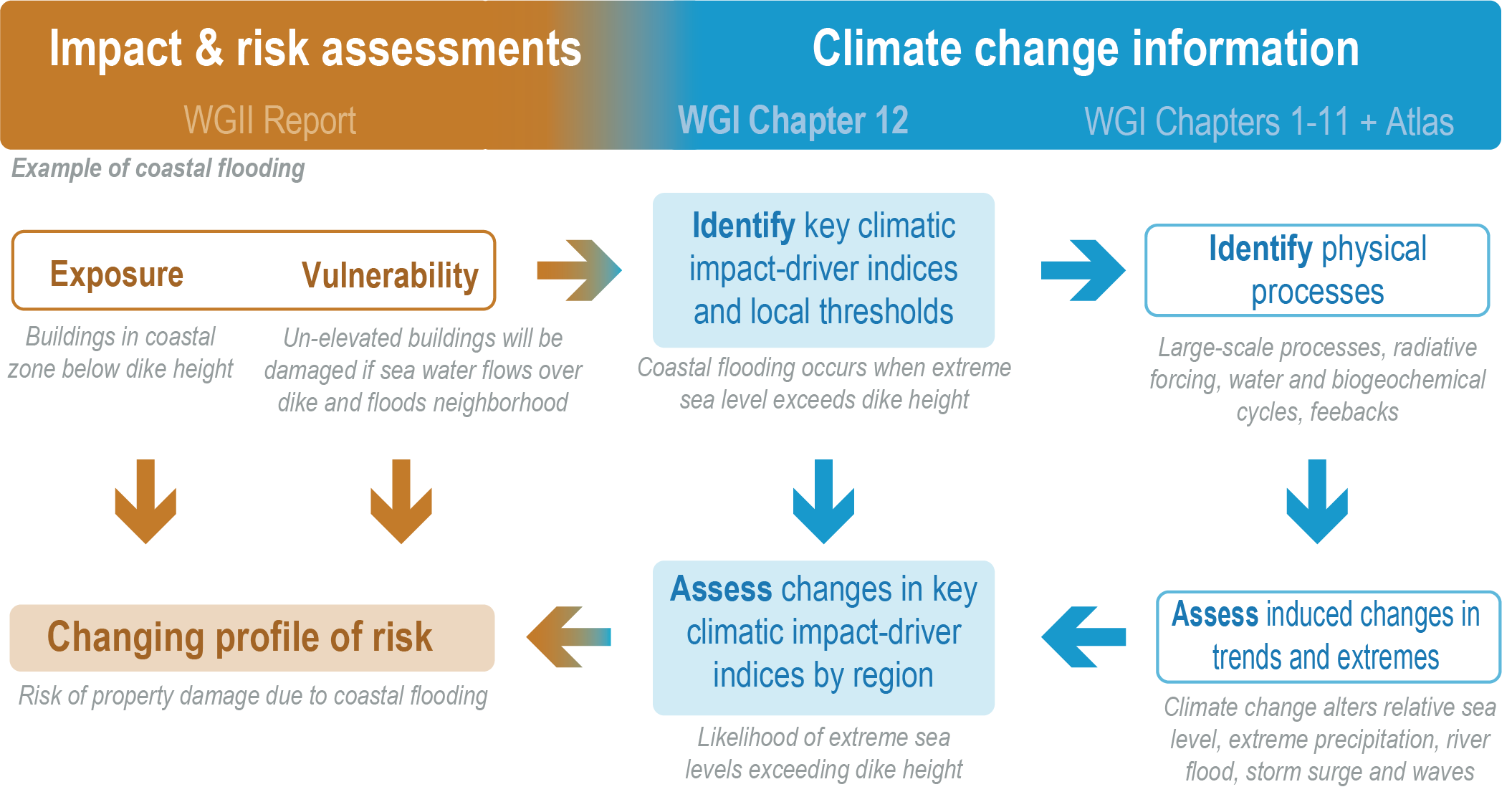

Figure 12.1 summarizes the rationale behind (Chapter 12 as the linkage (also referred to as a ‘handshake’) between WGI and WGII, illustrating how the changing profile of risk may be informed by an assessment of climatic impact-drivers, aligning WGI findings on physical climate change with WGII needs. The implementation of mitigation policy shifts may modulate hazard probability changes (i.e., by reducing emissions to limit global warming) as well as regional vulnerability and exposure. The assessment herein is organized around regional climatic impact-drivers, but also relates key indices and thresholds to increasing global drivers (such as mean surface warming) as a contribution to the assessment of ‘Reasons for Concern’ in WGII (O’Neill et al., 2017).

Figure 12.1 | Schematic diagram showing the use of climate change information (AR6 WGI chapters) for typical impacts or risk assessment (AR6 WGII chapters) and the role of Chapter 12, via an illustration of the assessment of property damage or loss in a particular region when extreme sea level exceeds dike height.

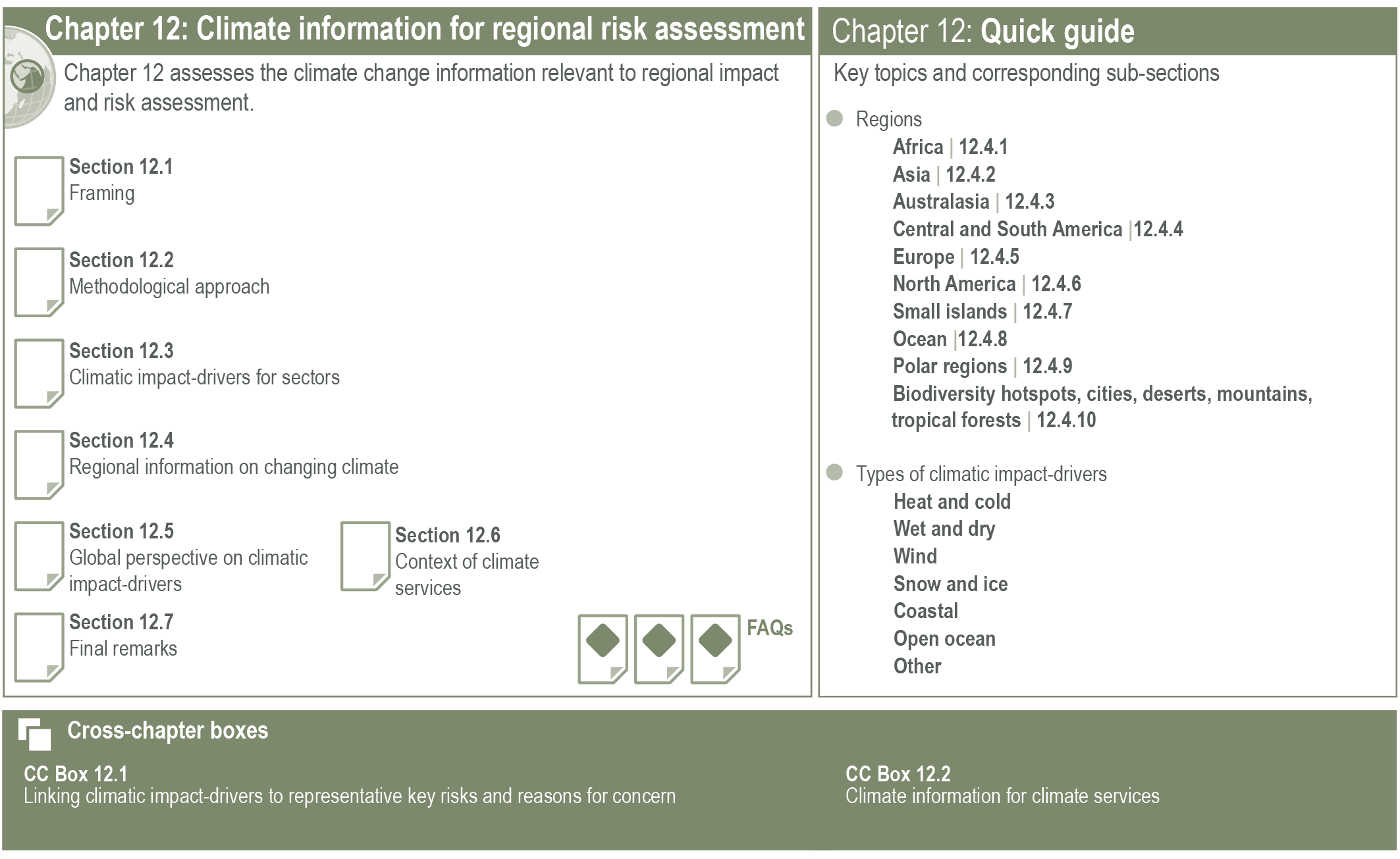

Figure 12.1 | Schematic diagram showing the use of climate change information (AR6 WGI chapters) for typical impacts or risk assessment (AR6 WGII chapters) and the role of Chapter 12, via an illustration of the assessment of property damage or loss in a particular region when extreme sea level exceeds dike height. The narrative of (Chapter 12 is illustrated in Figure 12.2. First, Section 12.2 defines a range of climatic impact-driver categories that are relevant for regional and sectoral impacts. Next, Section 12.3 identifies climatic impact-drivers and their relevant indices that are frequently used in the context of climate impacts in the WGII focus sectors (AR6 WGII Chapters 2–8). The assessment of changes in regional-scale climatic impact-drivers is then developed within Section 12.4 by continent, following the structure of the WGII assessment report regional chapters (AR6 WGII Chapters 9–15), and adding the polar regions, open/deep ocean and other specific zones corresponding to the WGII Cross-Chapter Papers. Section 12.5 then presents a global perspective (both bottom-up and top-down) on the change of regional climatic impact-drivers, including an assessment of the ‘emergence’ of climatic impact-drivers. Section 12.6 discusses how climate information is used in ‘climate services’, which encompasses a range of activities bridging climate science and its use for adaptation and mitigation decision-making (see also AR6 WGII Chapter 17). The chapter concludes with final remarks in Section 12.7.

The chapter includes two Cross-Chapter Boxes. Cross-Chapter Box 12.1 connects climatic impact-drivers to global climate drivers and levels of warming as an element of the ‘Reasons for Concern’ framework (AR6 WGII Chapter 16). An additional Cross-Chapter Box, including three case studies from Europe, Asia and Africa, describes how climate services draw upon and apply regional climate information to support stakeholder decisions (Cross-Chapter Box 12.2).

12.2 Methodological Approach

This section details the methodological approach followed in Chapter 12 and discusses the underlying rationale for the assessments presented herein. Scientific literature on vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation (as typically asssessed in IPCC WGII) is examined to identify relevant climatic impact-drivers (CIDs) that contribute to sectoral risks and opportunities. Projected changes in corresponding CID indices are then derived from existing literature on changes in the physical climate system, results of other AR6 WGI chapters, and direct calculations based on climate projections from several model ensembles.

The classification of climatic impact-drivers, the ways that they change (e.g., their magnitude or intensity, duration, frequency, timing and spatial extent) is described in this section. It is emphasized that this chapter assesses literature relating only to physical climatic impact-drivers, not their impacts on human systems or the environment. Thus, here we do not consider indicators including exposure or vulnerability as assessed by WGII, although the selection of climatic impact-drivers is informed by literature feeding into WGII.

(Chapter 12 assesses climate change information relevant for regional impact and for risk assessment in the seven main sectors corresponding to Chapters 2–8 of the WGII Assessment Report:

- Terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and their services (WGII Chapter 2);

- Ocean and coastal ecosystems and their services (WGII Chapter 3);

- Water (WGII Chapter 4);

- Food, fibre and other ecosystem products (WGII Chapter 5);

- Cities, settlements and key infrastructure (WGII Chapter 6);

- Health, well-being and the changing structure of communities (WGII Chapter 7);

- Poverty, livelihoods and sustainable development (WGII Chapter 8).

Many of these sectors also include assets affected by climate change that are important for recreation and tourism, including elements of ecosystems services, health and well-being, communities, livelihoods and sustainable development (see also Chapter 1 on the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), and the IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems (SRCCL; Hurlbert et al., 2019; IPCC, 2019c)).

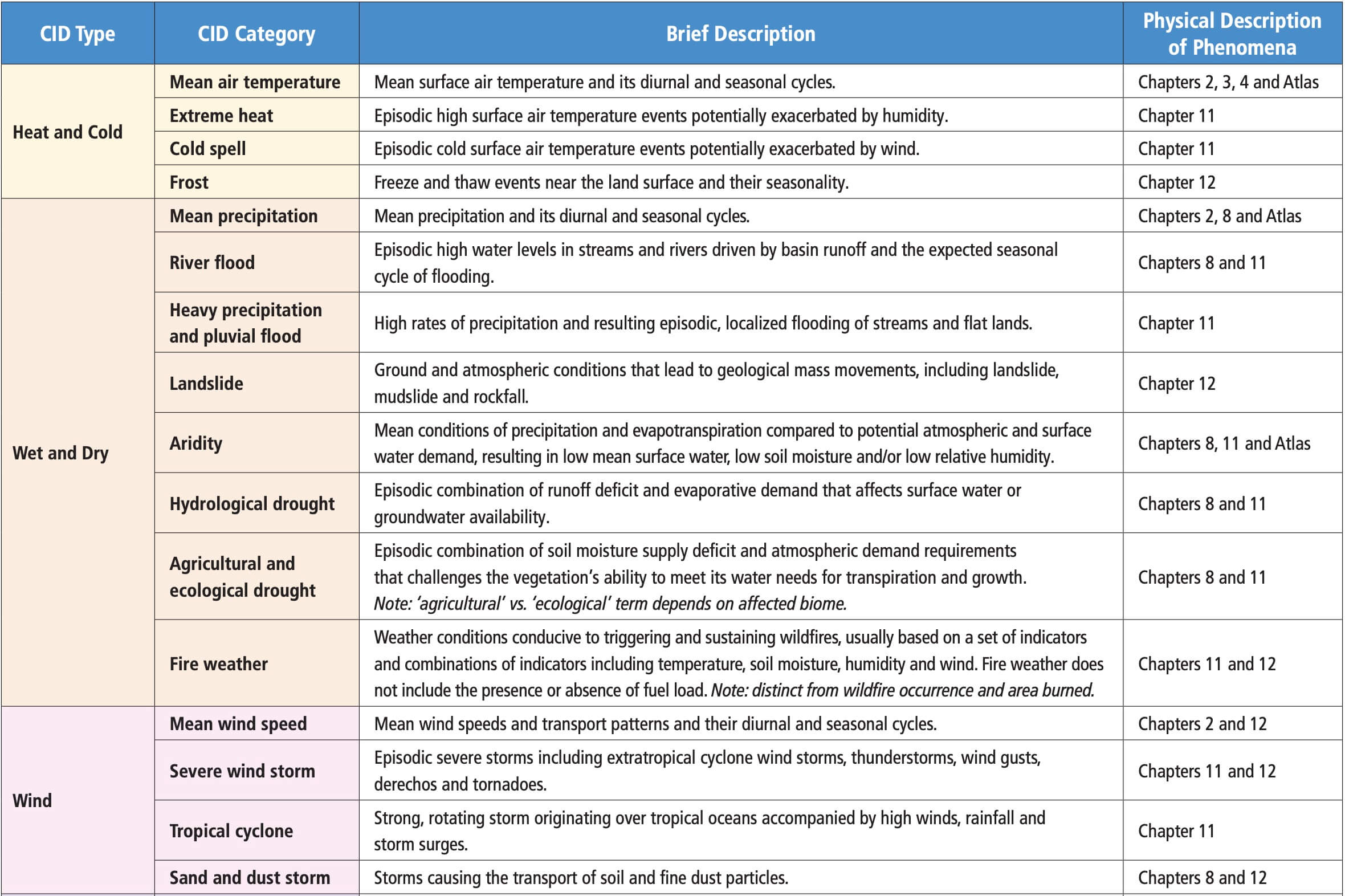

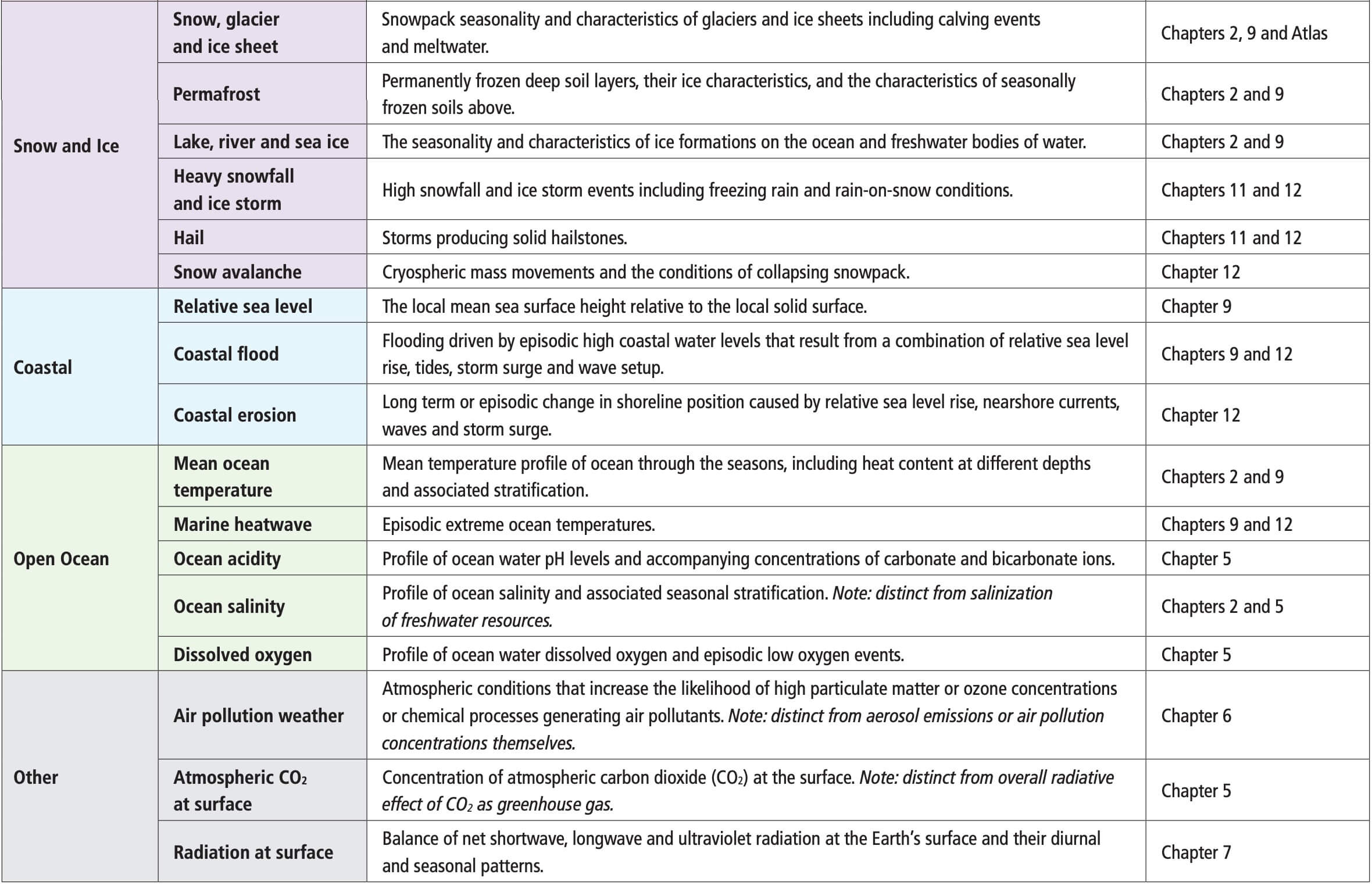

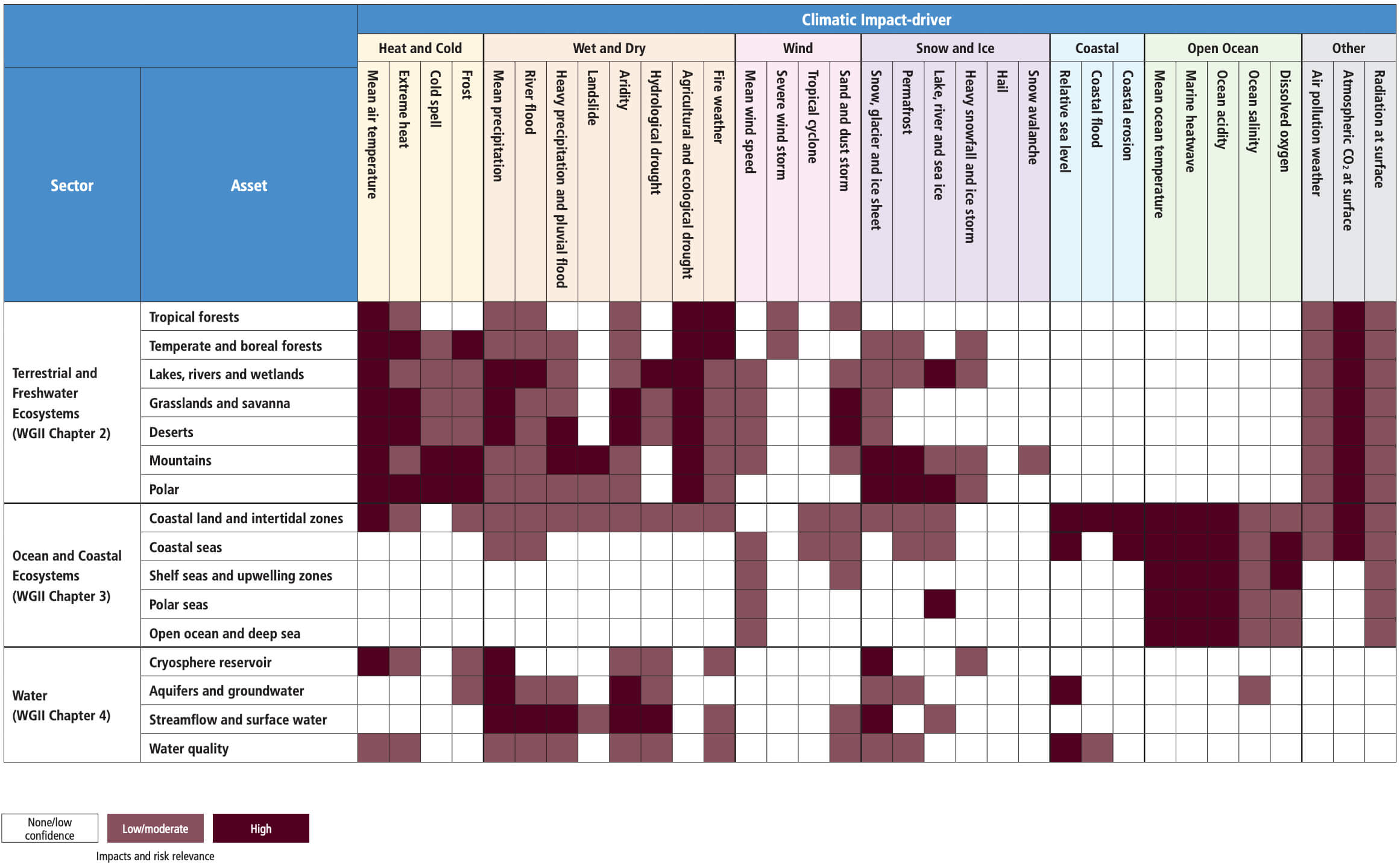

CIDs can be captured in seven main types: heat and cold; wet and dry; wind; snow and ice; coastal; oceanic and other. Table 12.1 provides an overview of the seven CID types and the CID categories associated with each type. The type ‘Other’ comprises additional CIDs that are not encompassed within the other six CID types, including air pollution weather (e.g., meteorological conditions that favour high concentrations of surface ozone, particulate matter or other air pollutants), near-surface atmospheric CO2 concentrations, and mean radiation forcing at the surface (which are, for example, relevant for plant growth). Icebergs, fog and lightning are also noted in this chapter but are not broadly assessed across all subsections. In addition, there can be changes in impacts associated with earthquakes that interact with climate variables and climate change, such as liquefaction (e.g., Yasuhara et al., 2012) during earthquakes, or earthquakes caused by snow and water changes (Amos et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2017), which are secondary effects on geophysical hazards that are not further assessed in this chapter. The characteristics and physical description of the climate phenomena or essential climate variables associated with each of these CID categories are assessed and described in previous Chapters 2–11 or (Chapter 12 directly as indicated in Table 12.1. The CID categories are further mapped on to different sectors in Section 12.3 (Table 12.2).

Potential changes in the seasonality of CIDs or the length and characteristics of seasons (e.g., changes in growing season length or pollen season) are also important as they may shift the timing of many CIDs with broad implications for sectors and regional stakeholders (Wanders and Wada, 2015; Cassou and Cattiaux, 2016; Hansen and Sato, 2016; Brönnimann et al., 2018; Marelle et al., 2018; Unterberger et al., 2018; Kuriqi et al., 2020). Episodic CIDs characterize impact-relevant conditions persisting from short to long time frames but eventually returning to normal conditions.

In some situations, phenomena causing severe impacts go well beyond a single extreme event or a single climate variable, and can include interaction of climatic conditions, such as sea level rise and storm surge (Wahl et al., 2015), precipitation in combination with strong winds (Martius et al., 2016) or flooding quickly followed by a heatwave (S.S.-Y. Wang et al., 2019; see also Section 10.5.2.4). Such compound events, particularly in the context of climate extremes, are assessed in Section 11.8. A combination of non-extreme climatic impact-drivers in time or space can also lead to severe impacts (Cutter, 2018).

Several climatic impact-drivers are reliant on many factors beyond their associated primary climatic phenomenon. For example, river flooding is heavily dependent on river management and engineering and could also be affected by tidal water levels due to sea level rise and/or storm surge. Coastal flooding could be affected by coastal protection structures, port and harbour structures, as well as river flows (on inlet-interrupted coasts). Coastal erosion could be influenced by coastal protection measures as well as fluvial sediment supply to the coast. Furthermore, air pollution weather is not the only or dominant driver, for instance, of surface ozone pollution, but precursor emissions from anthropogenic sources can play a significant role (Section 6.5). Chapter 12 focuses only on the influence of the atmospheric, land and oceanic conditions associated with the climatic impact-drivers and the confidence in the direction of CID changes given here does not take into account existing or potential future adaptation measures, unless otherwise stated.

For each CID category there can be a range of indices that capture the sector- or application-relevant characteristics of a climatic impact-driver as described in Sections 12.3 and 12.4. Indices for climatic impact-drivers that are based on absolute or percentile thresholds (e.g., daily maximum temperature above 35°C) can be affected by biases in climate model simulations, such as local or regional deviations of a simulated climate variable from observed values (Sillmann et al., 2014; Dosio, 2016). Where sensible (i.e., where reliable observational data are available and a climate model that fits for the desired purpose), the output of climate model simulations can be bias-adjusted, potentially involving advanced methods to account for multiple variables and extreme value statistics as assessed in detail in Cross-Chapter Box 10.2. Yet, there is no general agreement about which bias adjustment methods to apply, as artefacts can arise both from the climate model and from the bias adjustment method, and the number of available methods has considerably grown in recent years (for a detailed discussion of available methods and their performance see Sections 10.3.1.3.2 and 10.3.3.7.2, and Cross-Chapter Box 10.2). The WGI Interactive Atlas illustrates original and bias-adjusted CIDs (see Atlas.1.4.5).

A global perspective on climatic impact-drivers is provided in Section 12.5.1. Section 12.5.2 focuses on assessing evidence for the emergence (Section 1.4.2.2) of an anthropogenic climate change signal on the change in CIDs beyond natural climate variability, based on the literature assessed in other chapters and additional literature, at both global and regional scales. The process of generating user-relevant regional climate information in the context of co-production and climate services is assessed in Sections 10.5, 12.6, Box 10.2 and Cross-Chapter Boxes 10.3 and 12.2. Cross-Chapter Box 12.1 provides a global perspective on climatic impact-drivers related to their evolution for different GWLs (Section 1.6).

12.3 Climatic Impact-drivers for Sectors

Climate change becomes relevant for regional impact management and for risk assessment when changes in mean conditions or episodic events affect natural and societal assets (system components with socio-economic, cultural or intrinsic value) positively or negatively (Table 12.2). Decision makers, policymakers, risk managers and engineers therefore benefit from climate information that tracks key trends and exceedance of thresholds that represent crucial challenges for natural and human systems. While useful indices can vary widely for a given sector and precise tolerance threshold values are often unknown, common metrics, categories and progressions of threshold levels allow experts to recognize coherent messages concerning altered regional impacts and risk profiles under climate change.

This section surveys the links between CIDs and affected sectors; not to perform specific climate change impact or risk assessments (see AR6 WGII), but to describe key indices (among many) that quantify these links as guidance for stakeholders seeking applicable climate information. This survey builds on the work of the World Meteorological Organization Expert Team on Sector-Specific Climate Indices (ET-SCI) and previous IPCC assessments, notably AR5 WGII (Birkmann et al., 2014; IPCC, 2014a) and IPCC Special Reports (IPCC, 2018, 2019b, c) that have assessed climate hazards affecting sectors but is organized from a CID perspective drawing also upon recent summaries of sectoral hazards (Mora et al., 2018; ICOMOS, 2019; Yokohata et al., 2019). Impacts, risks and opportunities are rarely attributable to a single CID index or threshold, but climate shifts that push conditions outside of expected conditions and beyond tolerance levels are indicative of impact, risk or benefit given vulnerability and exposure. Focus is on direct sectoral connections of a CID (Hallegatte and Przyluski, 2010) rather than cascading or secondary effects (e.g., water-borne diseases following a flood, mental health challenges following a severe storm, or the effects of drought on poverty), as these are strongly affected by exposure, vulnerability and response, as discussed in the WGII Report.

Table 12.2 presents a summary of (Section 12.3 connections between CIDs as defined in Table 12.1 and key sectoral assets, utilizing the WGII organization of sectors (corresponding to WGII Chapters 2–8). Colours are shown for connections with at least medium confidence as assessed from sectoral impacts and risk literature, with relevance assessed according to the prominence of that specific CID/asset connection in analyses of current and future impacts and risk. Within each sector there is a multitude of specific sectoral systems that may be affected by CID increases and decreases, with consequences further distinguished by region, background climate and socio-economic or ecological context of the affected asset. Our aim is therefore to recognize important drivers and the common attributes of change within each CID that scientists and practitioners monitor to understand current and future challenges for important asset groups, thereby pointing to the climate information that needs to be tailored and analysed for impacts and for risk assessment (Section 12.6). Additional effects whereby CIDs affect each other (across Table 12.2 columns) are discussed as climatic phenomena within WGI. The ways sectoral assets affect each other (across Table 12.2 rows) are described throughout WGII, for example with information about the suitability of future climate zones and climate velocity challenges for a given asset potentially drawing from multiple CIDs and associated system tolerance thresholds (Hamann et al., 2015). Some broad connections indicated as low confidence may be under-represented in the literature or could be acute under specific circumstances.

12.3.1 Heat and Cold

12.3.1.1 Mean Air Temperature

Information about increasing mean annual and seasonal air temperature is relevant in the determination of suitable species range for terrestrial, freshwater and intertidal species (Thomas et al., 2004; Elith et al., 2010; Hincapie and Caicedo, 2013; Cooper, 2014; Krist et al., 2014; Lindner et al., 2014; Saintilan et al., 2014; Lenoir and Svenning, 2015; Myers-Smith et al., 2015; Urban, 2015; Thorne et al., 2017). Ocean ecosystems are affected by the ocean temperature CID (described in Section 12.3.6.1). Species redistribution and extinction studies also need information about climate velocity, a comparison of the pace of warming to geographical temperature gradients that indicates the rate at which a species would have to move to maintain its climatological temperature (Thomas et al., 2004; Loarie et al., 2009; Dobrowski et al., 2013; Burrows et al., 2014; Dobrowski and Parks, 2016; Sittaro et al., 2017) with some studies incorporating additional variables beyond temperature (Hamann et al., 2015). Many freshwater ecosystems are strongly constrained by stream and lake temperatures (Scheurer et al., 2009; Comte and Grenouillet, 2013; Contador et al., 2014; Knouft and Ficklin, 2017). Warmer and more stratified lake temperatures are more conducive to cyanobacteria blooms with implications for ecosystem health and water resource quality (Whitehead et al., 2009; Moss et al., 2011; Jones and Brett, 2014; Chapra et al., 2017; Shatwell et al., 2019). Consideration of nighttime and daytime temperature trends also elucidates different biophysical effects on vegetation (Peng et al., 2013). Changes in the seasonal timing caused by warming trends are critical to species ranges and ecosystem function (Pearce-Higgins et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2017b), and indices that characterize the onset of spring shed light on plant emergence and development (Ault et al., 2015).

Mean air temperature dictates many aspects of crop cultivation, livestock production, agroforestry and output from freshwater aquaculture and fisheries, as well as the potential for food contamination. Mean warming alters suitable cultivation zones for crop species (Bragança et al., 2016; Gendron St-Marseille et al., 2019; IPCC, 2019c) and tree species (Hanewinkel et al., 2013; Fei et al., 2017). Crop and ecosystem service productivity often responds directly to mean temperatures, although this is dependent on farming systems (Bassu et al., 2014; Challinor et al., 2014; Lobell and Tebaldi, 2014; Rosenzweig et al., 2014; Asseng et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Fleisher et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017; Smith and Fazil, 2019). Many studies relate plant development (phenology), insect generation cycles and pest outbreaks to growing degree days, an aggregation of daily thermal units above a threshold (e.g., Tmean>5°C) that accelerates with warmer conditions (Hof and Svahlin, 2016; Ruosteenoja et al., 2016; Tripathi et al., 2016). Many plants respond to changes in nighttime temperatures that affect respiration and transpiration rates (Narayanan et al., 2015; X. Chen et al., 2019), and warming of the soil column is also relevant to determine plant sprouting (Grotjahn, 2021). A number of indices have been developed to represent the length of the viable local growing season, including a count of days where Tmax>5°C (Mueller et al., 2015) or the period between a year’s first and last set of five consecutive days with a weighted Tmean≥10°C (G. Li et al., 2018). Warmer conditions and altered seasonality modify the range and metabolism of some pollinators, pests, diseases and weeds (Wolfe et al., 2008; Bebber, 2015; Aljaryian and Kumar, 2016; IPBES, 2016; Ramesh et al., 2017; Deutsch et al., 2018; Nyangiwe et al., 2018) and may reduce the effectiveness of winter storage for farmers and caching species (Sutton et al., 2016).

Warming raises accumulated seasonal heat indices used in livestock production, especially when humidity is high (Key et al., 2014; Lallo et al., 2018), determines aquaculture suitability and is important for wild fish species migration (Tripathi et al., 2016; Brander et al., 2017). Agricultural planners may also calculate how overall warming trends alter the accumulation of vernalization units or chilling hours for agricultural or horticultural crops (often accumulated temperature deficit below a given daily or hourly threshold; Dennis and Peacock, 2009; Luedeling, 2012; Tripathi et al., 2016; Grotjahn, 2021). Warming in the post-harvest is also important for the determination of spoilage and waste (Stathers et al., 2013) as well as food-borne diseases (Kovats et al., 2004; Mbow et al., 2019).

Warming affects road degradation rates (Chinowsky and Arndt, 2012; Espinet et al., 2016) and warming rates inform designs for long-term energy efficiency of buildings (Kalvelage et al., 2014). Mean temperature drives seasonal energy demand, often expressed using winter heating degree days (the accumulated deficit of daily temperatures below a ‘comfortable’ indoor temperature, e.g., 15.5°C) and summer cooling degree days (the accumulated excess of temperature above a ‘comfortable’ level, e.g., 18°C; Spinoni et al., 2015; Arnell et al., 2019). Energy resources may also need information on warming trends to determine suitable zones and overall productivity for biofuels and solar panels, the efficiency of which decreases with higher temperatures (Schaeffer et al., 2012; Wild et al., 2015; Solaun and Cerdá, 2019).

Health impacts and risk studies compare seasonal temperature conditions to limiting thresholds to understand range shifts and incubation rates for pathogens, disease vectors and zoonotic hosts (e.g., mosquitoes, ticks; Caminade et al., 2012, 2014; Eisen and Moore, 2013; Lima et al., 2016; Ogden, 2017; Monaghan et al., 2018) and warming of surface ocean and lake waters conducive to bacterial outbreaks (Baker-Austin et al., 2013; Jacobs et al., 2015; Vezzulli et al., 2015). Warmer conditions can also affect tourism (Kovács et al., 2017) and impact human health by lengthening the allergy season and increasing pollen concentration (Hamaoui-Laguel et al., 2015; Kinney et al., 2015a; Lake et al., 2017; Upperman et al., 2017; Sapkota et al., 2019; Ziska et al., 2019).

12.3.1.2 Extreme Heat

Impacts and risk assessments utilize a large variety of indices and approaches tailored to evaluate heat impacts on human health (Sanderson et al., 2017; C. Gao et al., 2018; McGregor and Vanos, 2018; Staiger et al., 2019; J. Zhu et al., 2019; Schwingshackl et al., 2021). A mixture of simple and complex heat stress indices often combine extreme temperatures and high humidity to capture human health challenges (Aström et al., 2013; Chow et al., 2016; Dahl et al., 2017a; Im et al., 2017; Coffel et al., 2018; J. Li et al., 2018; Vanos et al., 2020). Different optimum temperatures and extreme heat thresholds based on local distributions are needed to reflect acclimation of different locations and populations (Hajat et al., 2014; WHO, 2014; Kinney et al., 2015b; Russo et al., 2015; Petitti et al., 2016; Dosio, 2017; Cheng et al., 2018; Lay et al., 2018; Schwingshackl et al., 2021). Hot and humid heat episodes can be deadly (Mora et al., 2017), are associated with elevated hospital intake (Goldie et al., 2017) and lower safety and productivity of outdoor labourers (Dunne et al., 2013; Graff Zivin and Neidell, 2014; Kjellstrom et al., 2016; Pal and Eltahir, 2016; Y. Zhao et al., 2016; Mora et al., 2017; Watts et al., 2018; Orlov et al., 2019). Elevated nighttime temperatures prevent the human body from experiencing relief from heat stress (Zhang et al., 2012) and can be tracked over extended periods of sequential day and night heat extremes (Murage et al., 2017; Mukherjee and Mishra, 2018). Extreme heat also exacerbates asthma, respiratory difficulties and response to airborne allergens such as hay fever (Upperman et al., 2017). Extreme heat affects outdoor exercise such as the use of bike-share facilities (Heaney et al., 2019; Vanos et al., 2020). Large-scale recreational and sporting events such as marathons and tennis tournaments monitor heat extremes when determining the viability of host cities (Smith et al., 2016, 2018).

Short-term exposure of crops to temperatures beyond a critical temperature threshold can lead to lower yields and above a limiting temperature threshold, crops may fail altogether (Schlenker and Roberts, 2009; Lobell et al., 2012, 2013; Gourdji et al., 2013; Deryng et al., 2014; Schauberger et al., 2017; Tesfaye et al., 2017; Vogel et al., 2019). The exact level of these thresholds depends on species, cultivar and farm management (Hatfield and Prueger, 2015; Hatfield et al., 2015; Bisbis et al., 2018; Grotjahn, 2021). The timing of heatwaves is particularly important, as extreme heat is more damaging during critical phenological stages (Teixeira et al., 2013; Eyshi Rezaei et al., 2015; Fontana et al., 2015; B. Wang et al., 2017; Mäkinen et al., 2018). Extreme canopy temperatures, rather than 2 m air temperatures, may be a more robust biophysical indicator of heat impacts on crop production (Siebert et al., 2017). Heat stress indices based upon temperature and humidity determine livestock productivity as well as conception and mortality rates (Key et al., 2014; Dash et al., 2016; Pragna et al., 2016; Rojas-Downing et al., 2017).

Heat extremes factor in mortality, morbidity and the range of some thermally sensitive ecosystem species (Smith and Nagy, 2015; Ratnayake et al., 2019; Thomsen et al., 2019). Combined heat and drought stress can reduce forest and grassland primary productivity (Ciais et al., 2005; De Boeck et al., 2018) and even cause tree mortality at higher extremes (Teskey et al., 2015).

Extreme heat events raise temperatures in buildings and cities already warmed by the urban heat island effect (Gaffin et al., 2012; Oleson et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Mauree et al., 2019; Box 10.3) and can induce disruptions in critical infrastructure networks (Chapman et al., 2013). Heat affects transportation infrastructure by warping roads and airport runways (Chinowsky and Arndt, 2012) or buckling railways (Dobney et al., 2010; Dépoues, 2017; Chinowsky et al., 2019), and high temperatures reduce air density leading to aircraft take-off weight restrictions (Coffel et al., 2017; Palko, 2017; T. Zhou et al., 2018). Heat extremes increase peak cooling demand and challenge transmission and transformer capacity (Sathaye et al., 2013; Russo et al., 2016; Craig et al., 2018; X. Gao et al., 2018) and may cause transmission lines to sag or fail (Gupta et al., 2012). Thermal and nuclear electricity plants may be challenged when using warmer river waters for cooling or when mixing waste waters back into waterways without causing ecosystem impacts (Kopytko and Perkins, 2011; van Vliet et al., 2016; Tobin et al., 2018). Extreme temperature can also reduce photovoltaic panel efficiency (Jerez et al., 2015).

12.3.1.3 Cold Spells

The magnitude and timing (relative to developmental stages) of cold extremes (such as the typical coldest day of the year) set limits in the range of species habitat for ecosystems as well as for agricultural and forest pests (Osland et al., 2013; Cavanaugh et al., 2014; Parker and Abatzoglou, 2016; Brunner et al., 2018; Unterberger et al., 2018). Cold air outbreaks can lead to chilling injuries for crops (even above 0°C) and may kill outdoor livestock (particularly young animals; Mader et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013; Grotjahn, 2021), but are often necessary for crop chill requirements (Dennis and Peacock, 2009).

Increases in human mortality can occur on exceptionally cold days (e.g., <1st percentile of temperatures in winter) although thresholds and human-perceived temperatures linked to wind speed (i.e., ‘wind chill’) vary geographically due to acclimatization (Li et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2015; J. Li et al., 2018; J. Zhu et al., 2019). The timing of ‘unseasonal’ cold spells also affect human health (Kinney et al., 2015b). Extreme cold can increase heat and electricity demand (Stuivenvolt-Allen and Wang, 2019), cause water pipes to burst, and mechanically alter roads, railroads and buildings (Underwood et al., 2017).

12.3.1.4 Frost

Frost (Tmin<0°C) is a natural and fundamental aspect of many ecosystems, with more extreme conditions defined as ice (or icing) days (Tmax<0°C) (L.A. Vincent et al., 2018). Agricultural systems planning (e.g., planting calendars, seed selection or the opportunity to double-crop) requires information about the start and end of the frost-free season (Wypych et al., 2017; Wolfe et al., 2018). Crops and wild plants can be directly damaged by frost, but hard or killing frosts (at a threshold several degrees below freezing) can kill crops or lower harvest quality depending on duration (which relates to soil temperature penetration) and plant developmental stage (Crimp et al., 2016a; Cradock-Henry, 2017; G. Li et al., 2018; Mäkinen et al., 2018; Grotjahn, 2021). Earlier disappearance of snow cover reduces natural insulation that protects plants and burrowing animals from hard frost damages (Trnka et al., 2014; Mäkinen et al., 2018). In some cases an early season warm spell may reduce plant hardiness or induce fruit tree flowering that exposes plants to devastating subsequent frost impacts (Hufkens et al., 2012; Hatfield et al., 2014; Tripathi et al., 2016; Brunner et al., 2018; DeGaetano, 2018; Unterberger et al., 2018; Wolfe et al., 2018). Shifts in the seasonality of frozen soils also affect groundwater recharge and surface streamflow for water resource applications, particularly when peak precipitation is shifted to a season that no longer has frozen soils (Jyrkama and Sykes, 2007).

Regional information about the spring and autumn seasonal periods in which freeze-thaw cycles are common (such as the dates of first spring thaw and last spring frost, or the number of days where Tmax>0°C and Tmin<0°C) are particularly useful in estimating the rate of potential road and building damage or determining seasonal truck weight restrictions (Kvande and Lisø, 2009; Chinowsky and Arndt, 2012; Palko, 2017; Daniel et al., 2018). The altitude of the freezing level also identifies portions of mountain slopes where freeze/thaw transitions or changes in snowpack condition can influence landslide and snow avalanche hazards (Coe et al., 2018). The geographical distribution of frost is also a determining factor in the range of vectors for human diseases such as malaria (X. Zhao et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2020).

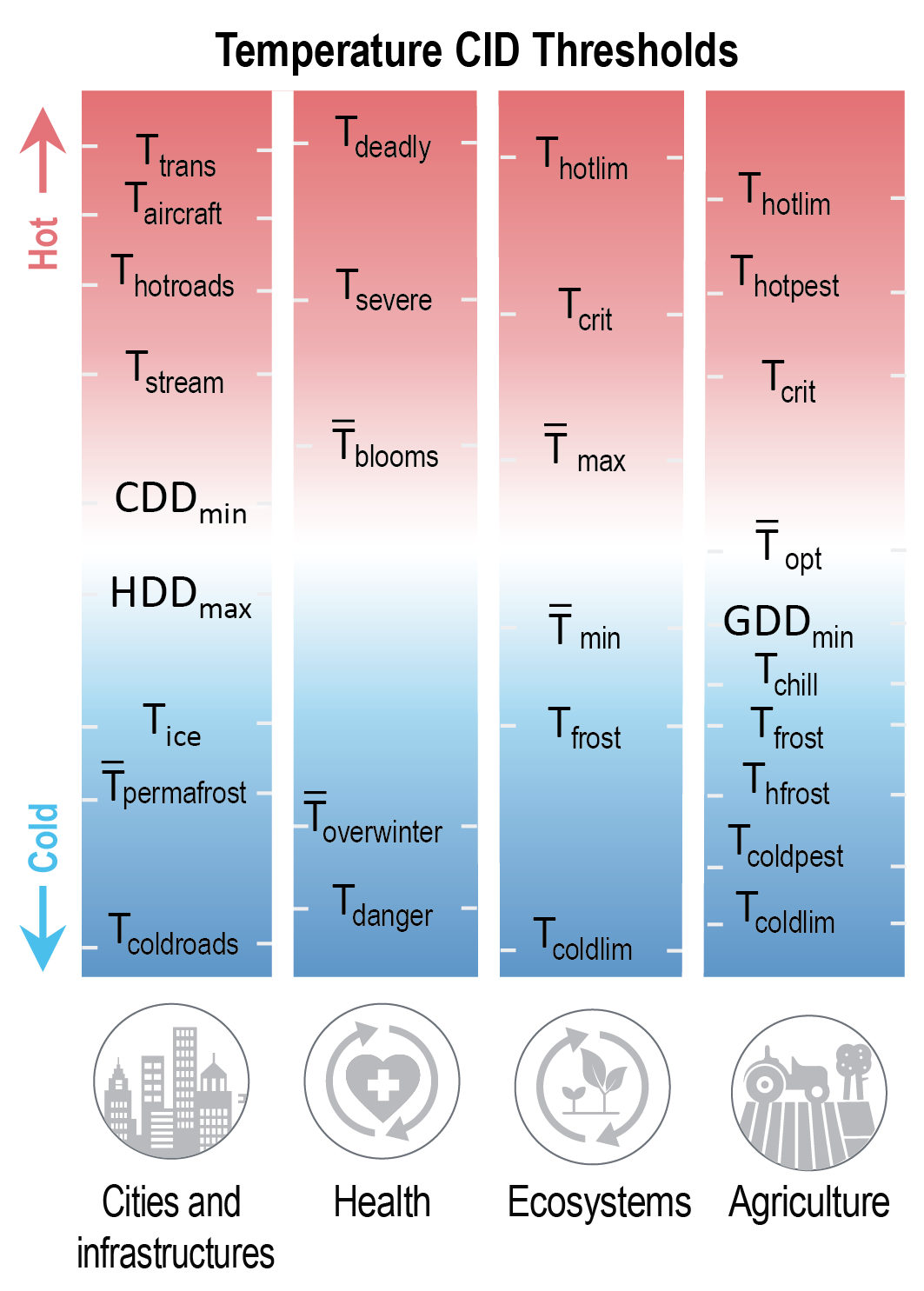

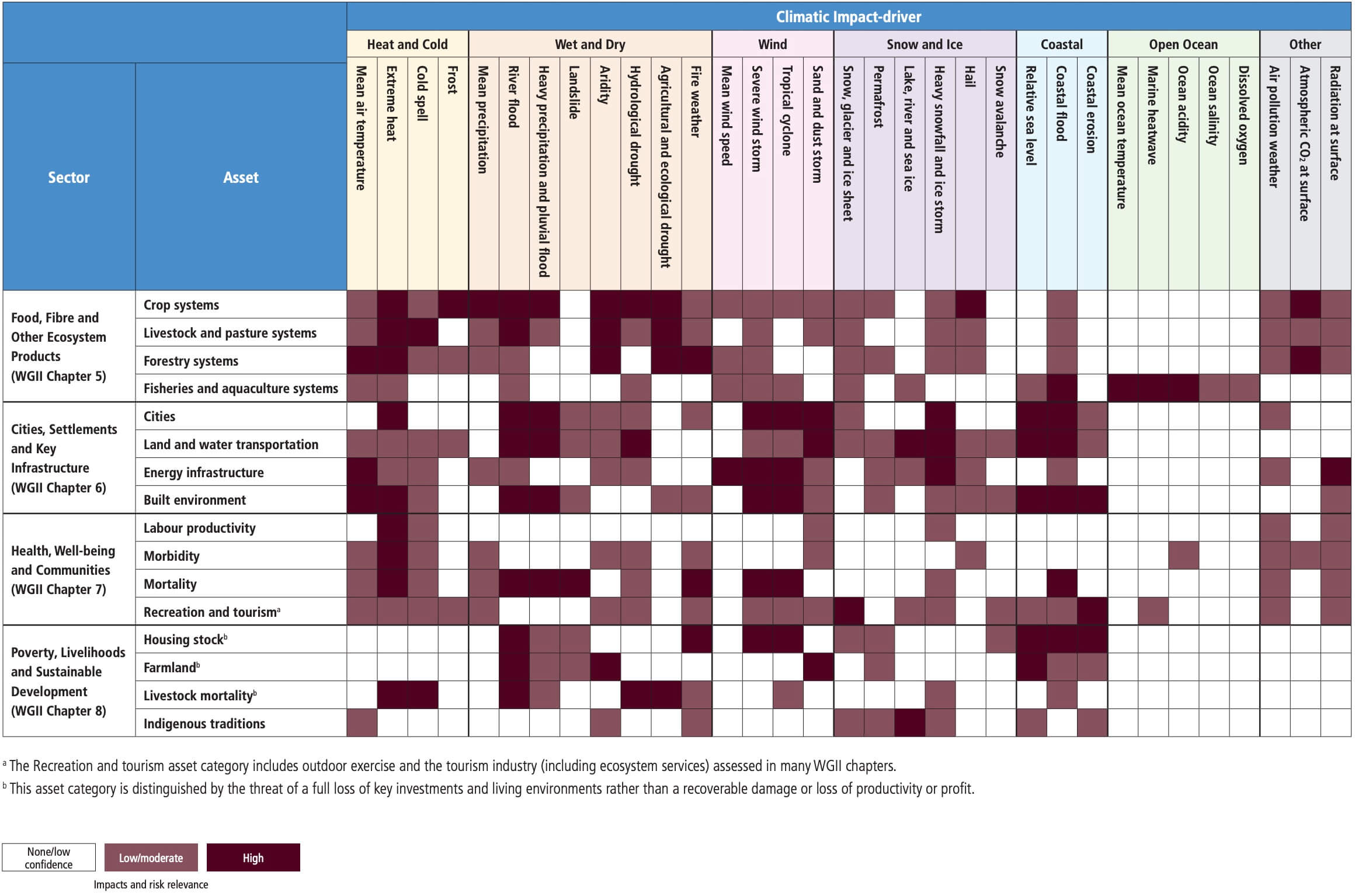

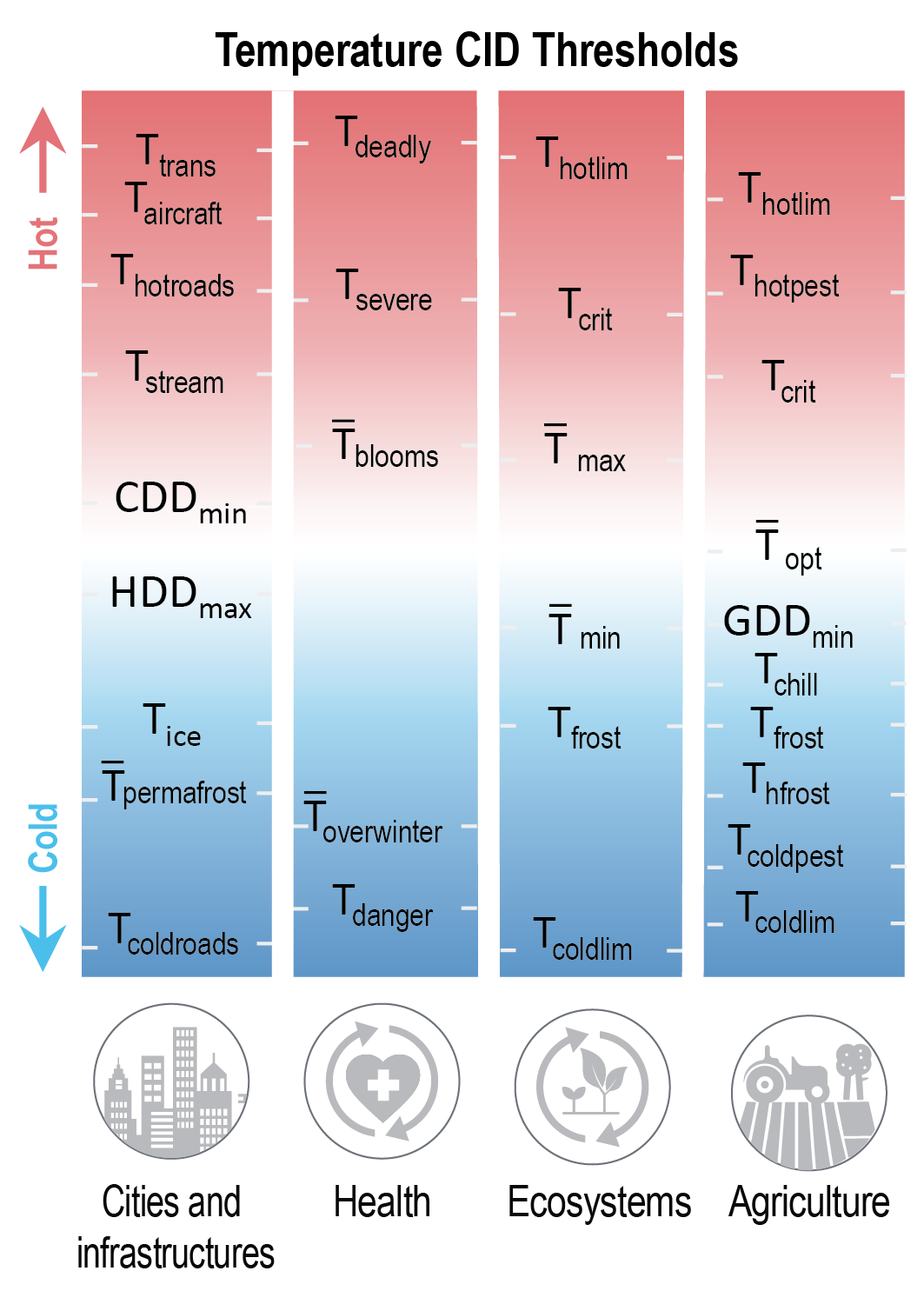

Figure 12.3 illustrates how successive heat and cold hazards can potentially affect important natural and human systems, with climatic pressures reaching new sectoral assets or becoming increasingly severe as conditions become more extreme. While the precise value of any CID threshold may depend strongly on local environmental and system characteristics, there are common patterns and interdependencies in the types of thresholds encountered. Changes in the regional profile of CIDs can thus substantially alter threshold exceedance likelihoods.

Figure 12.3 | Conceptual illustration of representative climatic impact-driver thresholds showing how graduating thresholds affect successive sectoral assets and lead to potentially more acute hazards as conditions become more extreme (exact values are not shown as these must be tailored to reflect diverse vulnerabilities of regional assets). Representative threshold definitions (T = instantaneous temperature; T= mean temperature): Cities and Infrastructures: Ttrans= temperature at which energy transmission lines efficiency reduced; Taircraft = temperature at which aircraft become weight-restricted for takeoff; Thotroads= temperature above which roads begin to warp; Tstream= temperature at which streams are not capable of adequately cooling thermal plants; CDDmin= minimum temperature for calculating cooling degree days; HDDmax= maximum temperature for calculating heating degree days; Tice= temperature at which ice threatens transportation; Tpermafrost = mean seasonal temperature above which permafrost thaws at critical depths; Tcoldroads= temperature below which road asphalt performance suffers. Health: Tdeadly= temperature above which prolonged exposure may be deadly (often combined with humidity for heat indices); Tsevere= temperature above which prolonged exposure may cause elevated morbidity; Tblooms= mean temperature for harmful algal or cyanobacteria blooms; Tdanger= level of dangerous cold temperatures (often combined with wind for chill indices); Toverwinter= temperature below which disease vector species cannot survive winter. Ecosystems (CID indices for air and ocean temperature): Thotlim and Tcoldlim= limiting hot and cold temperatures for a given species range; Tfrost = frost threshold; Tmax and Tmin= maximum and minimum suitable annual mean temperatures for a given species; Tcrit = critical temperature above which a given species is stressed. Agriculture: Thotlim= temperature above which a crop or livestock species dies; Thotpest = maximum (or ‘lethal’) temperature above which an agricultural pest/disease/weed cannot survive; Tcrit = temperature at which productivity for a given crop is depressed; Topt = optimal mean temperature for a given plant’s productivity; GDDmin= threshold temperature for growing degree days determining plant development; Tchill= temperature below which chilling units are accumulated; Tfrost = temperature below which frost occurs; Thfrost = temperature below which a hard frost threatens crops or livestock; Tcoldpest = minimum winter temperature below which a given agricultural pest cannot survive; Tcoldlim= minimum temperature below which a given crop cannot survive.

Figure 12.3 | Conceptual illustration of representative climatic impact-driver thresholds showing how graduating thresholds affect successive sectoral assets and lead to potentially more acute hazards as conditions become more extreme (exact values are not shown as these must be tailored to reflect diverse vulnerabilities of regional assets). Representative threshold definitions (T = instantaneous temperature; T= mean temperature): Cities and Infrastructures: Ttrans= temperature at which energy transmission lines efficiency reduced; Taircraft = temperature at which aircraft become weight-restricted for takeoff; Thotroads= temperature above which roads begin to warp; Tstream= temperature at which streams are not capable of adequately cooling thermal plants; CDDmin= minimum temperature for calculating cooling degree days; HDDmax= maximum temperature for calculating heating degree days; Tice= temperature at which ice threatens transportation; Tpermafrost = mean seasonal temperature above which permafrost thaws at critical depths; Tcoldroads= temperature below which road asphalt performance suffers. Health: Tdeadly= temperature above which prolonged exposure may be deadly (often combined with humidity for heat indices); Tsevere= temperature above which prolonged exposure may cause elevated morbidity; Tblooms= mean temperature for harmful algal or cyanobacteria blooms; Tdanger= level of dangerous cold temperatures (often combined with wind for chill indices); Toverwinter= temperature below which disease vector species cannot survive winter. Ecosystems (CID indices for air and ocean temperature): Thotlim and Tcoldlim= limiting hot and cold temperatures for a given species range; Tfrost = frost threshold; Tmax and Tmin= maximum and minimum suitable annual mean temperatures for a given species; Tcrit = critical temperature above which a given species is stressed. Agriculture: Thotlim= temperature above which a crop or livestock species dies; Thotpest = maximum (or ‘lethal’) temperature above which an agricultural pest/disease/weed cannot survive; Tcrit = temperature at which productivity for a given crop is depressed; Topt = optimal mean temperature for a given plant’s productivity; GDDmin= threshold temperature for growing degree days determining plant development; Tchill= temperature below which chilling units are accumulated; Tfrost = temperature below which frost occurs; Thfrost = temperature below which a hard frost threatens crops or livestock; Tcoldpest = minimum winter temperature below which a given agricultural pest cannot survive; Tcoldlim= minimum temperature below which a given crop cannot survive. 12.3.2 Wet and Dry

12.3.2.1 Mean Precipitation

Changes in mean precipitation alter total water resources and long-term surface, snowpack and groundwater reservoirs (Schewe et al., 2014). Annual and seasonal wet trends can alter the suitable geographic range of species, with implications for biodiversity and vector-borne diseases (Knouft and Ficklin, 2017; Smith et al., 2020). The rate at which higher total streamflow increases river erosion and changes sediment loading is relevant for fish breeding (Scheurer et al., 2009), the location of riverine salt fronts that affect coastal agriculture and ecosystems (Chun et al., 2018; Vu et al., 2018), coastal freshwater stratification (Baker-Austin et al., 2013; Bell et al., 2013), and the accretion of sediment in estuaries and beaches (Syvitski and Milliman, 2007). Wetter conditions may shift tourist appeal (Kovács et al., 2017) and alter the pace of degradation for paved and especially unpaved roads (Chinowsky and Arndt, 2012).

Many agricultural systems require minimum rainfall totals or rely upon irrigation (Mbow et al., 2019). The length of the wet season helps determine the potential for multiple cropping seasons, but inconsistency of wet season arrival times poses challenges for farm management (Waha et al., 2020). Wetter growing season conditions increase the chance of waterlogging, which can delay planting or damage planted seeds (Rosenzweig et al., 2002; Ben-Ari et al., 2018; Mäkinen et al., 2018; Wolfe et al., 2018; Kolberg et al., 2019; Grotjahn, 2021). Tomasek et al. (2017) calculated ‘workable days’ for agricultural machinery around planting and harvest time set in part by limits in soil moisture saturation below which farmers can utilize critical machinery with less rutting or soil compaction. Wetter conditions may also increase canopy moisture that is conducive to crop pathogens (Garrett et al., 2006; Kilroy, 2015; Grotjahn, 2021).

12.3.2.2 River Flood

A large variety of climate indices and models are utilized to understand how river flooding affects both natural or built environments with highly variable hazard thresholds, given unique local topography and engineered defences such as dams and polders (Arnell and Gosling, 2016; Ekström et al., 2018). Key transportation routes, built infrastructure and agricultural lands are threatened when floods exceed design standards commonly based around flood magnitudes of a given historic return period (e.g., 1-in-100-year flood event), an annual exceedance probability or precipitation intensity-duration-frequency relationships with key indices (e.g., 10-day cumulative precipitation) related to catchment size and properties (Hirabayashi et al., 2013; Arnell and Lloyd-Hughes, 2014; Kundzewicz et al., 2014; Arnell and Gosling, 2016; Dikanski et al., 2016; Gosling and Arnell, 2016; Forzieri et al., 2017; Fluixá-Sanmartín et al., 2018; Koks et al., 2019). Floods and high-flow events can scour river beds and elevate silt loads, reducing water quality and accelerating deposition in estuaries and reservoirs (Khan et al., 2018; Parasiewicz et al., 2019). Floods can knock down, drown or wash away crops and livestock, and partially submerged plants can have yield reduction depending on water turbidity and their development stage (Ruane et al., 2013; Shrestha et al., 2019). Basin snowpack properties may also be important during heavy rain events, as rain-on-snow events can lead to rapid acceleration of flood stages that threaten wildlife and society (Hansen et al., 2014).

12.3.2.3 Heavy Precipitation and Pluvial Flood

Heavy downpours can lead to pluvial flooding in cities, roadways, farmland, subway tunnels and buildings (particularly those with basements; Grahn and Nyberg, 2017; Palko, 2017; Pregnolato et al., 2017; Orr et al., 2018). Heavy precipitation may overwhelm city transportation and storm water drainage systems, which are typically designed using intensity-duration-frequency information such as the return periods for 1-, 6- or 24-hour rainfall totals (Kermanshah et al., 2017; Depietri and McPhearson, 2018; Rosenzweig et al., 2018; Courty et al., 2019). Heavy rain events can directly cause leaf loss and damage, or knock over crops, also driving pollutant entrainment and erosion hazards in terrestrial ecosystems and farmland, with downstream ramifications for water quality (Hatfield et al., 2014; Segura et al., 2014; Li and Fang, 2016; Chhetri et al., 2019). The proportion of total precipitation that falls in heavy events also affects the percentage that is retained in the soil column, altering groundwater recharge and deep soil moisture content for agricultural use (Fishman, 2016; Lesk et al., 2020).

12.3.2.4 Landslide

Landslides, mudslides, rockfalls and other mass movements can lead to fatalities, destroy infrastructure and housing stock, and block critical transportation routes. Climate models cannot resolve these complex slope failure processes (nor triggering mechanisms such as earthquakes), so most studies rely on proxies or conditions conducive to slope failure (Gariano and Guzzetti, 2016; Ho et al., 2017). Common indices include precipitation intensity-duration thresholds (Brunetti et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2012; Melchiorre and Frattini, 2012) and thresholds related to antecedent wet periods and extreme rainfall intensities (Alvioli et al., 2018; Monsieurs et al., 2019). Landslides and rockfalls may also be exacerbated by permafrost thaw and receding glaciers in polar and mountain areas (Cook et al., 2016; Haeberli et al., 2017; Patton et al., 2019).

12.3.2.5 Aridity

Aridity indices may track long-term changes in precipitation, evapotranspiration demand, surface water, groundwater or soil moisture (Sherwood and Fu, 2014; Herrera-Pantoja and Hiscock, 2015; B.I. Cook et al., 2020). Changes in soil moisture and surface water can shift the rate of carbon uptake by ecosystems (Humphrey et al., 2018) and alter suitable climate zones for wild species and agricultural cultivation (Feng and Fu, 2013; Garcia et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2016a; Schlaepfer et al., 2017; Fatemi et al., 2018; IPCC, 2019c) as well as the prevalence of related pests and pathogen-carrying vectors (Paritsis and Veblen, 2011; Smith et al., 2020). Water table depth, in relation to rooting depth, is also important for farms and forests under dry conditions (Feng et al., 2006). A reduction in water availability (via aridity or hydrological drought) challenges water supplies needed for for municipal, industrial, agriculture and hydropower use (Schaeffer et al., 2012; Arnell and Lloyd-Hughes, 2014; Schewe et al., 2014; Gosling and Arnell, 2016; van Vliet et al., 2016).

12.3.2.6 Hydrological Drought

Water managers often utilize a variety of hydrological drought indices and hydrological models to characterize water resources, low flow conditions and the potential for irrigation (Wanders and Wada, 2015; Mukherjee et al., 2018). Low flow volume and intermittency thresholds can indicate reductions in dissolved oxygen, more concentrated pollutants, and higher stream temperatures relevant for ecosystems, water resource quality and thermal power plant cooling (Feeley et al., 2008; Döll and Schmied, 2012; Schaeffer et al., 2012; Prudhomme et al., 2014; van Vliet et al., 2016). Low water levels may also restrict waterway navigation for commerce and recreation (Forzieri et al., 2018).

12.3.2.7 Agricultural and Ecological Drought

Agricultural and ecological drought indices relate to the ability of plants to meet growth and transpiration needs (Table 11.3; Zargar et al., 2011; Lobell et al., 2015; Pedro-Monzonís et al., 2015; Bachmair et al., 2016; Wehner et al., 2017; Naumann et al., 2018) and the timing and duration of droughts can lead to substantially different impacts (Peña-Gallardo et al., 2019). Drought stress for agriculture and ecosystems is difficult to directly observe, and therefore scientists use a variety of drought indices (Table 11.3), proxy information about changes in precipitation supply and reference evapotranspiration demand, the ratio of actual/potential evapotranspiration or a deficit in available soil water content, particularly at rooting level (Park Williams et al., 2013; Trnka et al., 2014; C.D. Allen et al., 2015; Svoboda and Fuchs, 2017; Mäkinen et al., 2018; Otkin et al., 2018). Severe water stress can lead to crop failure, in particular when droughts persist for an extended period or occur during key plant developmental stages (Hatfield et al., 2014; Jolly et al., 2015; Leng and Hall, 2019). Projections of high wind speed and low humidity (even for just a portion of the day) can also inform studies examining fruit desiccation and rice cracking (Grotjahn, 2021). Drought also raises disease infection rates for West Nile virus (Paull et al., 2017), and the alternation of dry and wet spells induces swelling and shrinkage of clay soils that can lead to sinkholes and destabilize buildings (Hadji et al., 2014).

12.3.2.8 Fire Weather

Complex fire weather indices shed light on conditions that increase the likelihood of wildfire and shifts in the fire season (Flannigan et al., 2013; Bedia et al., 2015; Jolly et al., 2015; Harvey, 2016; Littell et al., 2016; Westerling, 2016; Abatzoglou et al., 2019), which pose particularly acute challenges for indigenous communities (Christianson and McGee, 2019). Projection of future lightning frequency provides information on an important natural triggering mechanism, particularly when coupled with long-term warming and drying trends (Romps et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2015; Veraverbeke et al., 2017). Fuel aridity metrics also help determine vegetative fuel desiccation and therefore the ignitability, flammability and spread of fires when they occur (Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016). The presence of snow cover can influence the length of the fire season and the penetration of fire danger into new portions of the Arctic tundra (Young et al., 2017; Abatzoglou et al., 2019). Data on the changing characteristics of local wind circulations like the Santa Ana in California shed light on future intensity and spread patterns for fires (Jin et al., 2015). Fires also produce smoke plumes that reduce air and water quality (via deposition), adversely affecting health, visibility and water resources both near and far downwind (Dennekamp and Abramson, 2011; McKenzie et al., 2014; Dreessen et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Martin, 2016).

12.3.3 Wind

12.3.3.1 Mean Wind Speed

Changes in the speed and direction of prevailing winds can alter the profile of seed dispersal, windblown pest and disease vectors, animal activities, and dust or pollen dispersal affecting ecosystems, agriculture and human health (Reid and Gamble, 2009; Bullock et al., 2012; Hellberg and Chu, 2016; Nourani et al., 2017). Seasonal winds influence algal blooms, ecosystems and fisheries via lake mixing, ocean currents and coastal upwelling (Bakun et al., 2015; Townhill et al., 2018; Woolway et al., 2020). Changes to wind density also modify a region’s wind and wave renewable energy endowment (Schaeffer et al., 2012; Sierra et al., 2017; Craig et al., 2018; Devis et al., 2018; Tobin et al., 2018; Yalew et al., 2020). D. Li et al. (2020) and Karnauskas et al. (2018a) evaluated wind thresholds at turbine height (about 80–100 m above ground) including periods outside of cut-in (2.5–3 m s–1) and cut-out (about 25 m s–1) levels beyond which given turbines could not operate.

12.3.3.2 Severe Wind Storm

High winds associated with severe storms can destroy trees and houses, break plant stems and knock fruits, nuts and grains to the ground, with tolerance thresholds depending on crop species and developmental stage (Seidl et al., 2017; Lai, 2018; Elsner et al., 2019; Grotjahn, 2021). Severe storms particularly threaten energy infrastructure, with maximum wind speed associated with treefall and breaking of above-ground electrical transmission lines (Ward, 2013; Nik et al., 2020). The profile of heavy wind gusts is also required in the design of skyscrapers (C.-H. Wang et al., 2013) and bridges (Mondoro et al., 2018). Severe storms are difficult to simulate at the relatively coarse spatial scales of Earth system models, thus scientists often project changes by noting areas with increased convective available potential energy (CAPE) and strong low-level wind shear as these are conducive to tornado formation (Diffenbaugh et al., 2013; Tippett et al., 2016; Glazer et al., 2021).

12.3.3.3 Tropical Cyclone

Tropical cyclones and severe coastal storms can deliver wind, water and coastal hazards with the potential for widespread mortality and damages to cities, housing, transportation and energy infrastructure, ecosystems and agricultural lands (Burkett, 2011; NASEM, 2012; Bell et al., 2013; Wehof et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2016; Cheal et al., 2017; Godoi et al., 2018; Koks et al., 2019; Pinnegar et al., 2019). Storm planning is often tied to the Saffir –Simpson scale related to peak sustained wind speed (Izaguirre et al., 2021), with several indices focusing on storms’ overall power and energy, size and translation speed to anticipate destructive potential (Knutson et al., 2015; Wang and Toumi, 2016; Parker et al., 2018; Hassanzadeh et al., 2020).

12.3.3.4 Sand and Dust Storm

Sand and dust storms erode soils, damage crops and induce problems for health, transportation, mechanical equipment and built infrastructure corresponding to the magnitude and duration of high winds and particulate matter concentrations (Goudie, 2014; O’Loingsigh et al., 2014; Crooks et al., 2016; Barreau et al., 2017; Bhattachan et al., 2018; Al Ameri et al., 2019; Middleton et al., 2019). Dust events may be represented as the number of dust hours per year and by particulate matter (PM) concentrations (Leys et al., 2011; Spickett et al., 2011; Hand et al., 2016). Photovoltaic panels can lose energy production efficiency with dust accumulation (Patt et al., 2013; Javed et al., 2017). It is also useful to track dust storm deposition of nutrients necessary for coral and tropical forest systems, but they may also feed algal blooms harming lake and coastal ecosystems, health and recreation (Jickells et al., 2005; Hallegraeff et al., 2014; Gabric et al., 2016). Dust storms also cause air pollution and redistribute the soil-based fungus associated with Valley fever (Barreau et al., 2017; Coopersmith et al., 2017; Tong et al., 2017; Gorris et al., 2018).

12.3.4 Snow and Ice

Cryospheric changes are a focus of (Chapter 9 and were central to the recent IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC; IPCC, 2019b). Here we focus on the ways that scientists use snow and ice CIDs to understand current and future societal impacts and risks.

12.3.4.1 Snow, Glacier and Ice Sheet

A large number of indices have been used in water resource and ecosystem studies to track changes in snow under current and future climate conditions, including measurements of the snow water equivalent at key seasonal dates, the fraction of precipitation falling as snow, the first and last days of snow cover, and cold season temperatures (Mills et al., 2013; Pierce and Cayan, 2013; Berghuijs et al., 2014; Klos et al., 2014; Musselman et al., 2017; Rhoades et al., 2018). Impact studies also examine shifts in seasonal streamflow for snow-fed river basins (Mote et al., 2005; Pederson et al., 2011; Beniston and Stoffel, 2014; Coppola et al., 2014b, 2018; Fyfe et al., 2017; Islam et al., 2017; Knouft and Ficklin, 2017) as well as the geographic extent of snow cover and the depth of frosts when snow cover’s natural insulation is absent (Scheurer et al., 2009; Millar and Stephenson, 2015). Studies examining the impact of snow changes on winter recreation and transportation have used thresholds of about 30 cm snow depth or snow water equivalent >10 cm to determine the length of the season for alpine and cross-country skiing and snowmobiling (Damm et al., 2017; Wobus et al., 2017b; Spandre et al., 2019; Steiger et al., 2019; Abegg et al., 2021). Changes in snow quality also affect recreational activities (Rutty et al., 2017), and artificial snowmaking can augment recreational snowpack depending on the number of suitable snowmaking hours (e.g., where wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) <–2.2°C; Wobus et al., 2017b). Local detail may also be provided by tracking the seasonal rain–snow transition line across space and elevation (Berghuijs et al., 2014) (Pierce and Cayan, 2013; Berghuijs et al., 2014; Klos et al., 2014; Musselman et al., 2017).

Change in ice sheet and glacier spatial extent and surface mass balance is relevant for polar and high mountain ecosystems and downstream assets that rely on glacial water resources (J.R. Lee et al., 2017; Milner et al., 2017; Huss and Hock, 2018; Schaefli et al., 2019). The loss of glaciers reduces the thermal consistency of cold streams suitable for some freshwater species (Giersch et al., 2017), and parks and recreation areas may lose appeal as glaciers and seasonal snow cover retreat (Gonzalez et al., 2018; Wang and Zhou, 2019). Rapid glacial retreat can lead to glacial lakes and outburst floods that endanger downstream communities (Carrivick and Tweed, 2016; Cook et al., 2016; Harrison et al., 2018).

12.3.4.2 Permafrost

Changes in permafrost temperature, extent and active layer thickness are metrics that track how permafrost thaw below, for example, roads, airstrips, rails and building foundations in high-latitude and mountain regions may destabilize settlements and critical infrastructure (Pendakur, 2016; Derksen et al., 2018; Duvillard et al., 2019; Olsson et al., 2019; Streletskiy et al., 2019). Warmer conditions can also affect ecosystems, built infrastructure and water resources through thawing of especially ice-rich permafrost (≥20% ice content) and by thawing of ice wedges (Shiklomanov et al., 2017; Hjort et al., 2018), creation of thermokarst ponds and increased subsurface drainage for polar and high-mountain wetlands (Walvoord and Kurylyk, 2016; Farquharson et al., 2019) and the release of water pollutants such as mercury (Burkett, 2011; Schaeffer et al., 2012; Schuster et al., 2018).

12.3.4.3 Lake, River and Sea Ice

Reductions in the duration of thick sea, lake and river ice influence ecosystems as well as ice fishing, hunting, dog sledding and snowmobiling, which are recreation activities for some but vital aspects of many traditional indigenous communities (Durkalec et al., 2015; AMAP, 2017; Baztan et al., 2017; Arp et al., 2018; Rokaya et al., 2018; Knoll et al., 2019; Meredith et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2019). The seasonal extent of thin ice and iceberg density also determines the viability of shipping lanes and seasonal roads (Valsson and Ulfarsson, 2011; Pizzolato et al., 2016; AMAP, 2017; Mullan et al., 2017; Sturm et al., 2017), oil and gas exploration timing (Schaeffer et al., 2012) and the seasonality of phytoplankton blooms (Oziel et al., 2017). Sea ice is a critical aspect of some ecosystems and fisheries (Massom and Stammerjohn, 2010; Jenouvrier et al., 2014; Bindoff et al., 2019; Meredith et al., 2019). Various definitions of ‘ice free’ Arctic Ocean conditions can be tailored to represent transportation needs, including thresholds of ice coverage (<5% or <30% or <1 million km2) in September or over a four-month period (Laliberté et al., 2016; Jahn, 2018).

12.3.4.4 Heavy Snowfall and Ice Storm

Heavy snowfall is a substantial concern for cities, settlements and key transportation and energy infrastructure (Ward, 2013; Palko, 2017; Janoski et al., 2018; Collins et al., 2019). Heavy snowfall can interfere with transportation (Herring et al., 2018) and cause a loss of both work and school days depending on local snow removal infrastructure. Freezing rain and ice storms can be treacherous for road and air travel (Tamerius et al., 2016), and can knock down power and telecommunication lines if ice accumulation is high (Degelia et al., 2016). Rain-on-snow events can create a solid barrier that hinders wildlife and livestock grazing that is important to indigenous communities (Forbes et al., 2016). Shifts in the frequency, seasonal timing and regions susceptible to ice storms alter risks for agriculture and infrastructure (Lambert and Hansen, 2011; Klima and Morgan, 2015; Ning and Bradley, 2015; Groisman et al., 2016).

12.3.4.5 Hail

Information on the changing frequency and size distribution of hail can help stakeholders build resilience for agriculture, vehicles, transportation infrastructure and buildings, solar panels and wild species that see critical damage at particular hail size thresholds (Dessens et al., 2007; Webb et al., 2009; Patt et al., 2013; Fiss et al., 2019). Most climate models do not directly resolve hail and therefore studies often examine proxies associated with severe mesoscale storms (Tippett et al., 2015; Prein and Holland, 2018), although some regional studies now utilize hail-resolving models (Mahoney et al., 2012; Brimelow et al., 2017).

12.3.4.6 Snow Avalanche

Information about the changing frequency and seasonal timing of snow avalanches is important to assess threats to transportation routes, infrastructure, recreational skiing and people living in alpine communities (Lazar and Williams, 2008; Mock et al., 2017; Ballesteros-Cánovas et al., 2018; Hock et al., 2019). Like landslides and other mass movements, snow avalanches are not directly resolved by climate models and are thus tracked using proxy climate information describing snow avalanche susceptibility, particularly the snow water equivalent, and triggering mechanisms such as warm spells, high winds, rain-on-snow and heavy precipitation (Hock et al., 2019). The quality of snow also provides insight into avalanche hazards (Mock et al., 2017), with the seasonal altitude of wet snowpack (>0.5% liquid water by volume) particularly important in determining characteristics of potential avalanches (Castebrunet et al., 2014).

12.3.5 Coastal

The SROCC included in-depth discussions of threats facing the world’s coastlines (IPCC, 2019b) and Section 9.6 provides further discussion on coastal processes. Here we note major connections between coastal CIDs and ecosystem and societal assets near coastlines.

12.3.5.1 Relative Sea Level